Few phrases in financial history resonate as loudly as “Too Big to Fail” (TBTF). This concept, denoting institutions whose collapse would wreak havoc on the global economy, has become both a marvel of modern financial interconnectedness and a source of profound concern. But what makes these entities so critical, and how have governments around the world attempted to manage the immense risks they pose? This report will examine the intersection of financial institution wealth, power and government legislation enacted to protect consumers and ensure stability in financial markets.

The Anatomy of “Too Big to Fail”

At its core, TBTF is about systemic risk—the potential for a failure at a major financial player to cascade through the entire economy. While size is a significant factor, it is the interconnectedness of these institutions that magnifies their impact. A more precise term might be “too interconnected to fail,” as their operations are deeply entwined with global financial markets. These institutions act as central nodes in the financial network, and their stability underpins confidence in the broader economy.

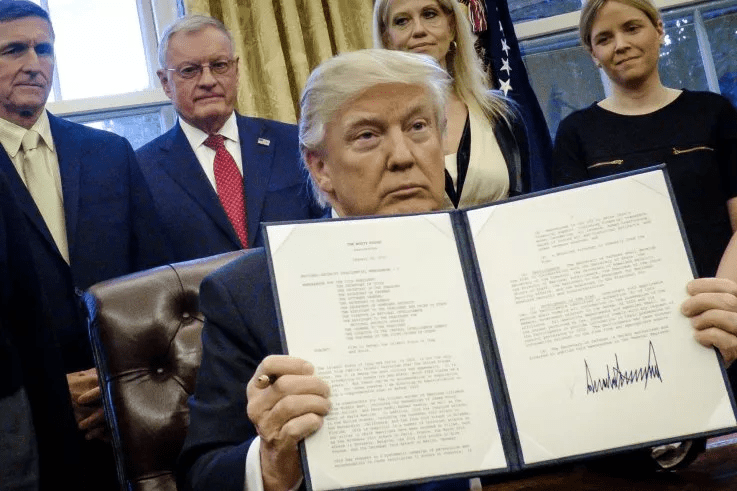

President Donald Trump holds up an executive order he signed that demands each time a federal agency promulgates a new regulation, it must eliminate at least two old ones.

Photo Credit: Pete Marovich/Getty

The government does not formally designate any institution as “Too Big to Fail” to avoid encouraging moral hazard, yet systemic risk remains a recognized concern. Institutions critical to market stability are closely monitored, with regulators imposing stringent oversight to mitigate potential crises.

Lessons from History: 2008 and Beyond

The 2008 financial crisis provided a stark lesson in the dangers of TBTF institutions. The near-collapse of major entities like Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, and government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac exposed the vulnerabilities of a tightly connected financial ecosystem. These failures precipitated one of the most severe global recessions since the Great Depression.

To stave off a complete financial meltdown, U.S. regulators—including the Treasury, Federal Reserve, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC)—deployed extraordinary measures. Bailouts were extended to several institutions, with taxpayer-backed funds injected to stabilize them. Lehman Brothers was the notable exception, and its collapse highlighted the devastating consequences of inaction. The crisis spurred widespread reforms, but the echoes of 2008 remain.

Lehman’s collapse was caused by a number of factors including the subprime mortgage crisis. Lehman was highly leveraged due to aggressive growth, excessive borrowing, and a risk-taking business model.

Fast forward to 2023, and the financial sector once again confronted systemic risks. The failure of three banks, including Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, each holding over $100 billion in assets, reignited fears of instability. Emergency interventions by the FDIC, such as guaranteeing uninsured deposits, underscored the persistent vulnerabilities within the system despite years of regulatory advancements.

The Double-Edged Sword of Bailouts

While bailouts provide short-term stability, they raise fundamental concerns about fairness and economic efficiency. Critics argue that bailouts create moral hazard—the notion that institutions shielded from failure are incentivized to take excessive risks. Knowing the government may step in during crises, some firms might prioritize high-risk, high-reward strategies, increasing the likelihood of systemic disruptions.

Some financial institutions are perceived to be “too big to fail” (TBTF), meaning that their failure would trigger financial instability.

This dynamic has led to a persistent debate: Should regulators focus on preventing failures at all costs, or should market discipline—allowing firms to face the consequences of their actions—take precedence? Policymakers must strike a delicate balance between these opposing philosophies.

Regulatory Reforms in the Post-2008 Era

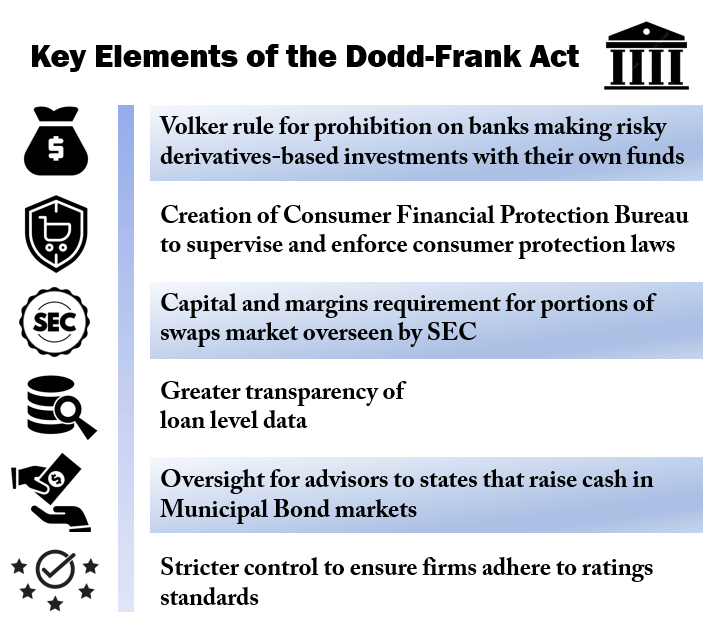

In response to the 2008 crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act introduced sweeping reforms aimed at curbing the risks associated with TBTF institutions. Key measures included:

- Enhanced Prudential Regulation (EPR): Administered by the Federal Reserve, EPR imposed stringent oversight on large bank holding companies (BHCs) and systemically important nonbank financial firms. Requirements included stress testing, resolution planning (“living wills”), and enhanced capital and liquidity standards.

- Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA): Designed to wind down failing institutions in a controlled manner, OLA was modeled on traditional bank resolution mechanisms. While it aimed to prevent taxpayer-funded bailouts, its effectiveness remains untested.

- Designation of Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs): Initially, entities such as AIG, Prudential, and GE Capital were designated as SIFIs. However, all were de-designated by 2018 due to regulatory changes and evolving business models.

Despite these reforms, challenges persist. The 2023 failures of SVB and Signature Bank exposed gaps in the regulatory framework, particularly for institutions falling below the most stringent thresholds. Tailored rules for mid-sized banks, intended to reduce burdens, may have inadvertently heightened systemic risks.

The Challenges of Market Discipline

Market discipline, the concept that creditors and investors naturally curb excessive risk-taking, has proven unreliable in preventing crises. When bailouts remain a plausible outcome, stakeholders—believing they will be shielded from losses—may fail to hold firms accountable. This undermines the credibility of “no bailouts” policies and perpetuates a cycle of risk-taking and government intervention.

Moreover, market discipline alone cannot address the complexities of modern financial systems. Large institutions often operate with opaque structures and intricate financial products, making it difficult for investors to accurately assess risk. These challenges necessitate robust regulatory oversight to complement market mechanisms.

Theories of Illuminati Control in Financial Markets

Conspiracy theories about the Illuminati—a purported secret society seeking global domination—have long captivated imaginations, especially regarding their alleged influence over financial markets and world events. These theories often assert that an elite group of powerful individuals manipulates economic systems to maintain control and consolidate wealth.

Proponents of these theories point to the concentration of wealth and influence among major financial institutions as evidence of a hidden agenda. They suggest that key financial players coordinate to create artificial market fluctuations, destabilize economies, or engineer crises to advance their interests. Some claims even tie these actions to broader political objectives, such as influencing elections or promoting global governance initiatives.

Critics argue that these theories lack concrete evidence and oversimplify complex financial and political dynamics. While the notion of coordinated manipulation is intriguing, most experts attribute market behavior to systemic factors, such as regulatory gaps, investor sentiment, and macroeconomic trends, rather than secretive cabals.

The enduring appeal of Illuminati theories reflects broader societal anxieties about inequality, transparency, and the perceived concentration of power. Regardless of their veracity, these narratives highlight the importance of fostering trust in financial systems and ensuring accountability among global institutions.

Alternatives to TBTF Regulation

Some policymakers advocate for structural solutions to mitigate TBTF risks. Proposals include capping institution size or reinstating elements of the Glass-Steagall Act, which once separated commercial and investment banking activities. While these approaches aim to reduce systemic risk, they also carry potential downsides, such as stifling innovation, disrupting established financial systems, and inconveniencing customers.

“We support too big to fail. We want the government to be able to take down a big bank like JP Morgan and it could be done. We think Dodd-Frank, which we supported parts of, gave the FDIC the authority to take down a big bank.” Source: Jamie Diamond. J.P Morgan/Chase

Another alternative is activity-based regulation, focusing on inherently risky practices rather than the institutions themselves. This approach seeks to address systemic vulnerabilities regardless of where they occur. However, implementing effective activity-based regulations has proven challenging, and the pace of financial innovation often outstrips regulatory adaptation.

The Path Forward: Balancing Stability and Innovation

Navigating the complexities of TBTF requires a multifaceted approach. Policymakers must balance the benefits of financial stability with the need to foster innovation and growth. While reforms like Dodd-Frank have strengthened oversight, the financial system’s inherent dynamism demands constant vigilance and adaptability.

Key questions remain: Should regulators focus on institutions or activities? How can moral hazard be minimized without stifling economic dynamism? And what role should market discipline play in a world where the specter of bailouts persists?

Addressing these issues is no small task. Financial systems thrive on risk, but unchecked risk invites disaster. Policymakers must carefully calibrate their strategies to ensure a resilient financial architecture. For TBTF institutions, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The world is watching, and the lessons of the past remain ever relevant.

Sources & Image Credits:

{1} Too Big to Fail: Financial Titans and the Illuminati. Image Credit: PWK International Advisers. 04 Jan 2025

{2} President Donald Trump holds up an executive order he signed that demands each time a federal agency promulgates a new regulation, it must eliminate at least two old ones. Photo Credit: Pete Marovich/Getty

{3} Lehman’s collapse was caused by a number of factors including the subprime mortgage crisis. Lehman was highly leveraged due to aggressive growth, excessive borrowing, and a risk-taking business model. Caption: Christie’s employees carry the Lehman Brothers sign as part of the sale of its art after its collapse. Photo Credit: Oli Scarff Getty Images

{4} Bailout Funds: Some financial institutions are perceived to be “too big to fail” (TBTF), meaning that their failure would trigger financial instability. Image Credit: PWK International Advisers

{5} Key Elements of the Dodd-Frank Act. Infographic Source and Credit: PWK International Advisers

{6} Theories of Illuminati Control in Financial Markets: Image Credit: PWK International Advisers

{7} “We support too big to fail. We want the government to be able to take down a big bank like JP Morgan and it could be done. We think Dodd-Frank, which we supported parts of, gave the FDIC the authority to take down a big bank.” Source: Jamie Diamond. J.P Morgan/Chase. Photo Credit: Undisclosed

About PWK International Advisers

PWK International provides national security consulting and advisory services to clients including Hedge Funds, Financial Analysts, Investment Bankers, Entrepreneurs, Law Firms, Non-profits, Private Corporations, Technology Startups, Foreign Governments, Embassies & Defense Attaché’s, Humanitarian Aid organizations and more.

Services include telephone consultations, analytics & requirements, technology architectures, acquisition strategies, best practice blue prints and roadmaps, expert witness support, and more.

From cognitive partnerships, cyber security, data visualization and mission systems engineering, we bring insights from our direct experience with the U.S. Government and recommend bold plans that take calculated risks to deliver winning strategies in the national security and intelligence sector. PWK International – Your Mission, Assured.