This report aims to demystify the U.S. federal government’s complex funding system—specifically, the way that appropriated funds are categorized, managed, and constrained by purpose and time. Commonly referred to as the “Color of Money,” these categorizations are not just budget lines in a spreadsheet; they are the legal and operational scaffolding upon which American innovation, defense capability, and day-to-day government function are built. If you want to understand how Washington actually pays for war, innovation, logistics, and operations, your journey to an informed understanding begins here.

At first glance, terms like RDT&E, O&M, and Procurement may appear to be the alphabet soup of bureaucracy. But underneath the jargon is a highly structured system designed to ensure fiscal discipline, align resources with mission needs, and maintain legislative oversight.

The system imposes clear constraints on how money can be used, by whom, for how long, and for what purpose. Misunderstanding the distinctions between these categories isn’t a minor clerical issue—it can result in project delays, audit failures, and violations of federal law.

This report will walk you through each major appropriation category, how it affects innovation and operations, and what it reveals about the federal government’s strategy for managing risk, accelerating delivery, and upholding accountability. Drawing from internal presentations, budget policy documents, and strategic examples, we will show why the Color of Money is not just a financial mechanism—it’s a lens into the business of government itself.

What Is Government Money and Why It’s “Colored”

At its core, government money is appropriated funding that is legally authorized by Congress for specific uses. These funds are governed by public laws and must be obligated within certain timeframes and under strict rules. This concept, known in federal finance as the “Color of Money,” refers to the various categories of appropriations, each with its own color-coded identity based on how it can be spent, how long it’s valid, and what types of programs it can support. The origin of this process is enshrined in the U.S. Constitution, which states that no money shall be drawn from the Treasury without an appropriation made by law.

The government doesn’t just fund operations and development indiscriminately—it carefully separates money into categories like Research, Development, Test & Evaluation (RDT&E), Procurement, and Operations & Maintenance (O&M), among others. Each appropriation type carries a different “color,” and that color defines how the money can legally be used. For instance, RDT&E funds are typically used for early-stage innovation and have a two-year obligation window, while Procurement funds are used to acquire major end items and are fully funded for a three-year window. These distinctions help Congress control how federal dollars are spent and ensure that taxpayer money is aligned with strategic outcomes.

RDT&E (3600):

2-year obligation window, 5-year spend period, 7-year lifecycle.

Procurement (3010, 3080):

3-year obligation window, 5-year spend period, 8-year lifecycle.

O&M (3400):

1-year obligation window, no multi-year spend, 1-year lifecycle.

Understanding the Color of Money is critical for anyone working in government contracting, acquisition strategy, or technology development. A contractor seeking to prototype a new AI sensor platform, for example, needs to know whether their work is classified as R&D (and thus eligible for 3600 funds) or a purchase of a finished system (requiring Procurement funding). Misclassifying or misusing funds doesn’t just invite administrative headaches—it can trigger audits, repayment demands, or even legal penalties. In this way, the Color of Money acts as both a budgeting discipline and a safeguard for the integrity of public spending.

The Big Three

Federal funding for defense and innovation is dominated by three key appropriations: RDT&E (Research, Development, Test & Evaluation), Procurement, and Operations & Maintenance (O&M). These three colors of money form the foundation of how the U.S. government funds new technologies, sustains military readiness, and equips its forces. Each serves a distinct function, operates on a different timeline, and comes with a specific set of rules. Understanding how each of these appropriations works—and how they interact—is essential for navigating the acquisition landscape or proposing a new program to a government customer.

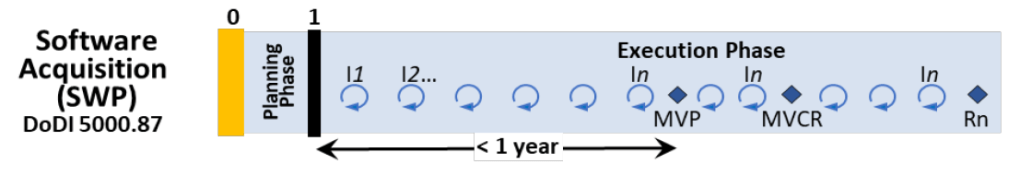

RDT&E funds (code 3600) are the government’s vehicle for exploring new ideas and maturing them into viable technologies. These funds support activities like prototyping, system design, early testing, and science and technology studies. They are incrementally funded, meaning agencies typically only obligate one year’s worth of funding at a time for multi-year projects. This approach allows for flexibility but also introduces delivery risk if a project slips from one fiscal year into the next. RDT&E funding is available for obligation over two years, with a total lifecycle of seven years before cancellation. It is the most common funding stream for startups, labs, and firms pursuing cutting-edge capabilities that haven’t yet been fielded.

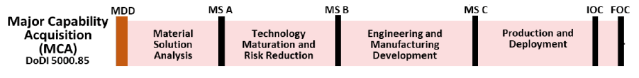

Procurement funds (codes 3010, 3020, 3080) are used to buy major systems—jets, satellites, missiles, vehicles, and even enterprise IT. These funds must cover the full cost of an item or contract quantity at the time of award, and are available for obligation over three years. Procurement is how innovation becomes infrastructure: once a prototype proves itself, the transition to Procurement marks a shift from invention to scaling. These funds are fully committed to deliverables and are typically tied to long lead-time manufacturing programs. With an eight-year lifecycle, including five years to spend obligated funds, Procurement is the most rigid of the three—but also the most capital-intensive.

Finally, Operations & Maintenance (O&M) funds (code 3400) are the lifeblood of day-to-day military and civilian operations. These funds cover everything from base operations and maintenance of equipment to training, civilian salaries, fuel, and minor construction. O&M is annual money, meaning it must be obligated in the year it is appropriated, and any unused balances expire. This short lifespan makes O&M funds extremely responsive but also creates pressure to obligate quickly, especially toward the end of the fiscal year. For defense contractors, misusing O&M funds to support long-term deliverables or capital equipment can lead to significant compliance issues.

Why Color Matters in Innovation Strategy

The Color of Money is not just a budgeting technicality—it’s a strategic constraint that directly affects how quickly and effectively the government can adopt new technologies. Innovation in the defense sector, for example, often begins with RDT&E funding to support research, exploration, and early-stage development. But if a program is ready for transition and Procurement funds aren’t lined up, it can stall indefinitely. This funding gap—sometimes called “the valley of death”—has derailed countless promising programs, not because the technology failed, but because the money wasn’t in the right form at the right time.

For industry partners, understanding how their offering aligns with funding categories can make or break a contract opportunity. A company proposing an AI system that requires extensive integration and long-term support must know whether its work qualifies as RDT&E, Procurement, or even O&M. Misalignment leads to delayed awards, contract modifications, or budget rejections. Strategically savvy firms shape their proposals and technical milestones around the lifecycle of available funds. For example, they may deliver early testing under RDT&E and then design a seamless transition into a Procurement-funded production contract.

Program managers inside the government must also navigate the color divide carefully. The rules around incrementally funded R&D, fully funded procurement, and annual O&M spending leave little room for creative workarounds. A system designed to promote fiscal responsibility can also introduce delays if programs aren’t mapped properly across funding types. The smartest innovation strategies are the ones that don’t just design brilliant technology—they design compliant, color-aware funding paths from concept to deployment.

The Gray Areas and Creative Pitfalls

While the rules surrounding federal appropriations are designed to promote clarity and accountability, the real-world application of those rules often gets murky. In the fast-paced world of defense tech and digital services, mission urgency can pressure program offices and contractors to stretch definitions and blur funding lines. For example, some teams may attempt to use O&M funds to prototype equipment or begin limited production under RDT&E without proper justification—moves that may seem efficient but risk violating federal appropriations law. These gray areas can lead to what’s known as a “propriety of funds” issue—using the wrong color for the wrong purpose.

One common pitfall is end-of-year spending, when agencies rush to obligate expiring O&M funds to avoid reversion to the Treasury. While it’s legal to execute valid obligations late in the fiscal year, using funds simply because they’re available or about to expire runs afoul of the Bona Fide Need Rule. Similarly, using a particular appropriation because “it’s the only funding we have” is not a valid rationale. The law requires that funds match the timing, purpose, and amount of the actual requirement. These pressures create an environment where well-meaning teams may engage in what auditors call “creative financing,” which invites scrutiny from the DoD Inspector General or the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

The consequences of misuse are not trivial. A color mismatch in funding can lead to Anti-Deficiency Act violations, forced de-obligations, contract renegotiations, and congressional reporting requirements. These setbacks don’t just hurt programs—they hurt reputations and slow down innovation. Successful government innovators and business development teams know how to stay within the lines without losing momentum. That means working closely with comptrollers, justifying appropriations choices clearly, and ensuring every dollar is spent with both mission and law in mind.

How Today’s Color Schemes Shape Tomorrow’s Technologies

The structure of appropriated funding doesn’t just reflect how the government pays for capabilities—it shapes which technologies are prioritized, how quickly they scale, and how long they survive. A promising capability developed under RDT&E might show immediate battlefield utility, but if Procurement dollars aren’t aligned in the following fiscal year, the program can stall or die. Conversely, some legacy programs continue receiving Procurement and O&M support long after their strategic relevance has faded, simply because they are already embedded in the budget cycle. In this way, the “Color of Money” serves as both a blueprint and a bottleneck in the evolution of American power.

This dynamic is especially visible in emerging technology sectors like AI, autonomous systems, hypersonics, and cyber defense. These technologies often require multi-phase investment strategies—starting with science and technology research, moving into prototyping, and then transitioning to scaled deployment. Each phase requires a different color of money and careful coordination between program managers, acquisition strategists, and congressional appropriators. Failure to build a phased funding strategy results in delays, reprogramming requests, or innovation being handed off to commercial competitors. Getting the color sequence right is often the difference between a breakthrough fielding and a “program of record” that never leaves the drawing board.

Looking ahead, budget reformers and strategic planners have called for more flexible funding models to accommodate the pace of modern innovation. Concepts like “Colorless Money,” rapid acquisition authorities, or bridge funds aim to reduce friction between appropriation categories. However, until such reforms are implemented at scale, anyone working in the business of government must operate within the current framework. That means designing technology strategies that align not only with user needs and technical feasibility—but also with the right kind of money, at the right time, in the right hands.

Beyond the Color – How Government Money Tells the Story of Strategy

While this report introduces the mechanics of appropriated funds and their lawful uses, the story doesn’t end there. If you follow the money long enough, you begin to see patterns—strategic intentions disguised as budget codes, power dynamics hidden in procurement lines, and national priorities reflected in spreadsheets more than speeches.

Money as Strategy: The Budget as National Posture

Every dollar in the federal budget reflects a judgment about what the United States believes it needs to deter, disrupt, or destroy. The massive surge in 3600 (RDT&E) funding over the past five years, for example, isn’t just about “more tech”—it signals a pivot toward autonomy, AI-driven targeting, and multidomain integration. Similarly, Procurement line items in INDOPACOM show preparation for a possible high-end maritime conflict, while O&M investments in Europe reflect renewed attention on readiness and alliance support.

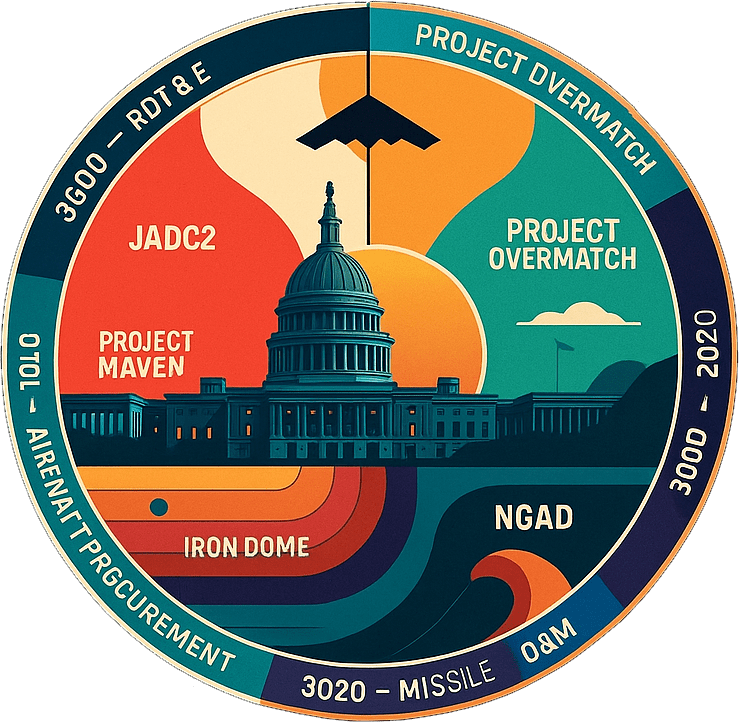

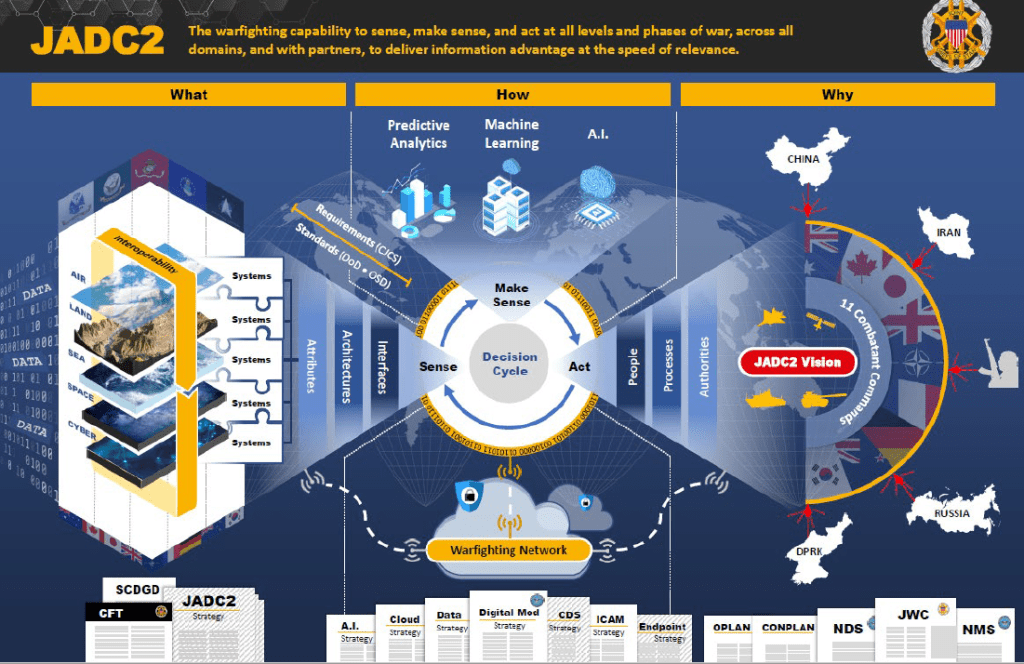

Programs That Paint the Budget

Flagship systems—like JADC2, Project Maven, or NGAD—don’t just show up in one appropriation category. They migrate. They evolve. They change “color.” For instance, JADC2 began as a research initiative (3600), then matured into a partially fielded command-and-control network funded via 3080 (Other Procurement) and 3400 (O&M). The transition of these programs tells a larger story about how innovation becomes capability.

The Endgame: Where the Money Goes (or Doesn’t)

Each appropriation has a strict expiration date, and unspent balances often vanish before they’re put to use. Every year, billions are returned to the Treasury—not because they weren’t needed, but because they weren’t mobilized fast enough. This happens even as urgent tech programs fail to scale, or fielded systems lack maintenance support.

In Washington, you don’t just have to win the money. You have to use it on time—or lose it forever.

Why This Matters

The original concept of the “Color of Money” provides structure and accountability. But once you zoom out, you see that it’s not just a framework—it’s a form of storytelling. Appropriations are how government expresses intent. They’re signals to contractors, allies, and adversaries. They reflect not only legal authority but strategic vision—or sometimes, the lack of one.

That’s why understanding the Color of Money isn’t just for accountants. It’s for strategists, innovators, and anyone shaping the future of U.S. power.

Top 6 Takeaways

1. The “Color of Money” isn’t metaphorical—it’s foundational.

Every federal dollar comes with legal instructions for how, when, and where it can be spent. Understanding appropriation categories is essential for anyone involved in defense, innovation, or public-sector delivery. It’s not just financial literacy—it’s strategic intelligence.

2. RDT&E, Procurement, and O&M funds serve different missions.

RDT&E (green) fuels discovery and development. Procurement (blue) funds the purchase and deployment of systems. O&M (red) keeps the enterprise running. Each color has a different lifecycle, obligation period, and risk profile.

3. Misusing funds—even with good intentions—invites real consequences.

Using the wrong color can lead to Anti-Deficiency Act violations, program delays, or GAO audits. There’s no “gray area” defense when it comes to federal appropriations law. Align purpose with the proper funding stream from the start.

4. Innovation often dies at the “color transition” point.

Many promising technologies fail not because they don’t work, but because there is no plan—or no available funding—to transition them from RDT&E into Procurement. Smart programs map their budget pathway before development begins.

5. O&M is the most flexible—but also the most misunderstood.

O&M funds must be obligated annually and are often rushed into action late in the fiscal year. While useful for sustaining operations, they are not designed for acquisition or development. Treating them as such is a red flag for compliance.

6. Strategic leaders design around the color wheel.

The best business development and program management professionals understand how to sequence funding, shape proposals by appropriation type, and engage with Congress and agency comptrollers. In government work, knowing your colors is knowing your craft.

Conclusion

Understanding the Color of Money is more than a technical skill—it’s a strategic imperative. In the complex ecosystem of federal programs, each appropriation type governs not only what can be done, but when and how it can be delivered. From warfighters on the front lines to scientists in government labs, success often hinges on matching the right work with the right money. When that match is off, even the best ideas can stall, contracts can be voided, and opportunities can slip through the cracks.

As the pace of innovation accelerates and the threats facing the United States grow more complex, the need for agility in funding is greater than ever. Yet until appropriation law evolves to meet that demand, navigating this environment means knowing the rules and working within them. Contractors, agency leaders, and policymakers must treat funding strategy as an essential part of capability development—not an afterthought. A brilliant prototype without a Procurement plan is just a PowerPoint slide waiting to expire.

At PWK International, we believe that the future of government innovation depends on a clearer understanding of how money moves through the system. This report was designed to help readers not just decode the terminology, but to see the deeper relationship between appropriations and national capability. By treating money as a strategic instrument we can help build a more responsive, accountable, and effective government enterprise.

We support Hedge Funds, Financial Analysts, Investment Bankers, Entrepreneurs, Law Firms, Non-profits, Private Corporations, Technology Startups, Foreign Governments, Embassies & Defense Attaché’s, Humanitarian Aide organizations and more.

References and Related Reading

Principles of Federal Appropriations Law (“GAO Red Book”)

https://www.gao.gov/legal/appropriations-law

The Government Accountability Office’s authoritative reference explaining the legal rules governing federal appropriations, including the purpose, time, and amount restrictions that underpin the “color of money.”

DoD Budget Materials and Justification Books

https://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials/

The Department of Defense Comptroller’s official repository of annual budget documentation detailing how funds are allocated across appropriations like RDT&E, Procurement, and O&M.

Congressional Research Service: DoD RDT&E Appropriations Structure

https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R44711

A detailed overview of how Research, Development, Test & Evaluation funding is structured across the military services and how it supports national security technology development.

U.S. Constitution, Article I – Appropriations Clause

https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/article-1/section-9/clause-7/

The constitutional foundation for federal budgeting, establishing that no money may be drawn from the Treasury without congressional appropriation.

Office of Management and Budget – Federal Budget Process Overview

https://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/

An overview of the federal budgeting process, explaining how presidential budget proposals, congressional appropriations, and execution shape government spending.

Congressional Budget Office – Defense Budget Analysis

https://www.cbo.gov/topics/defense-and-national-security

Independent analysis of defense spending trends and how budget allocations influence force structure, modernization, and readiness.

Center for Strategic and International Studies – Defense Budget Analysis

https://www.csis.org/programs/international-security-program/defense-budget-analysis

A widely cited research program that analyzes trends in U.S. defense spending and the strategic implications of budget priorities.

Congressional Research Service – Defense Acquisition Process

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10553

A concise overview of the U.S. defense acquisition lifecycle and how funding phases correspond to development, procurement, and sustainment.

DoD Budget Overview (“Green Book”)

https://comptroller.defense.gov/Budget-Materials/Budget2024/

An official high-level overview of defense budget allocations and trends across appropriation categories.

Defense Innovation Unit – Commercial Innovation and DoD Adoption

https://www.diu.mil/about

Explains the role of DIU in bridging commercial innovation into defense programs and the funding pathways that enable transition.

Air Force Research Laboratory – Science & Technology Portfolio

https://www.afrl.af.mil/About-Us/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/104473/air-force-research-laboratory/

Overview of AFRL’s role in early-stage RDT&E investment and technology maturation for future military capabilities.

DoD Inspector General – Financial Oversight and Accountability Reports

https://www.dodig.mil/reports.html

Audits and oversight reports illustrating how improper use of appropriated funds can trigger compliance and legal consequences.

National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) – Legislative Framework

https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/2670

The annual law that sets policy direction for defense programs and authorizes funding levels that Congress later appropriates.

Advanced Reading: Innovation Transition and the “Valley of Death”

Government Accountability Office – Defense Acquisitions Annual Assessment

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-106831

GAO’s annual review of major defense acquisition programs highlighting systemic challenges in transitioning technologies from development to procurement.

RAND – Improving Technology Transition in the DoD

https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2124.html

A RAND study exploring policies and organizational reforms needed to improve the transition of defense technologies into operational programs.

Defense Innovation Unit – Commercial Solutions Opening (CSO) Guide

https://www.diu.mil/work-with-us

Explains how DIU uses flexible acquisition authorities to move commercial technology from prototype to operational deployment.

Congressional Research Service – Other Transaction Authority (OTA)

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45521

An overview of OTA authorities that enable faster prototyping and experimentation outside traditional acquisition pathways.

GAO – DoD Use of Other Transaction Agreements

https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-22-105357

A GAO assessment of how the Department of Defense uses OTAs to accelerate technology development and prototype projects.

Air Force AFWERX – Innovation Pipeline Overview

https://afwerx.com/

Describes how AFWERX programs such as SBIR and Prime aim to accelerate transition of commercial technologies into Air Force programs.

Congressional Research Service – Defense Acquisition Process Overview

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10553

A concise explanation of the stages of the defense acquisition lifecycle and where many technologies fail to transition.

Pingback: Disrupt Five-O | Big Busts with High Tech |

Pingback: War Committees | How Congress Quietly Controls Innovation |

Pingback: UAP | Unidentified Anomaly or Demand Signal? |

Pingback: Unfair Fights |

Pingback: Unfair Fights |

Pingback: Valley of Death | A Strategic Guide to Government Contract Vehicles |