New Battlefields and Strategic Competition | Semiconductors are more than microchips; they are the critical infrastructure of modern life. Every smartphone, missile guidance system, and artificial intelligence model depends on them. Their production requires a uniquely complex global supply chain, with design in the United States, fabrication in Taiwan and South Korea, and critical manufacturing equipment supplied by the Netherlands and Japan. Whoever leads in this domain commands both economic and strategic advantage.

Since 2018, the United States has tightened export controls to limit China’s access to advanced chips. The reasoning is clear: advanced semiconductors are the foundation for artificial intelligence, quantum computing, and next-generation military capabilities. If China achieves independence in this sector, Washington fears it will close the technological gap and gain tools for both military advantage and authoritarian control at home.

The story of semiconductor sanctions is therefore not simply about trade or market competition. It is about the rules of global power in the 21st century. Much as oil pipelines once determined geopolitical alignments, control of silicon supply chains now defines who sets the pace in economics, defense, and international influence.

America’s Playbook: Keep the Crown Jewels

The U.S. strategy has unfolded in escalating phases. First came company-specific bans, such as placing Huawei and Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) on the Commerce Department’s Entity List. This move restricted their ability to purchase U.S. technologies. Over time, the controls expanded beyond individual companies to include broad categories of chips and chipmaking equipment. By 2020, Washington extended its Foreign Direct Product Rule, ensuring that even foreign firms could not sell advanced chips to China if U.S. intellectual property or equipment was involved.

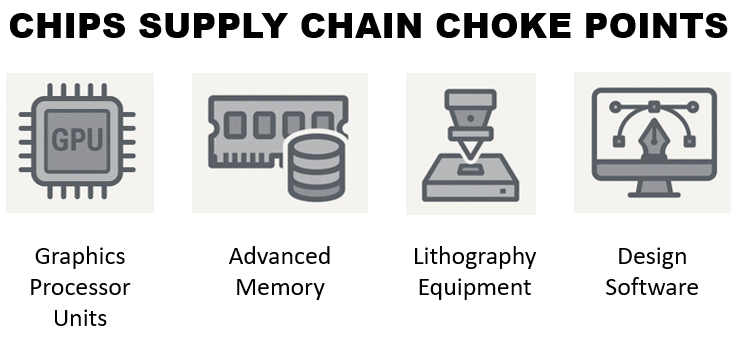

The logic was to construct a “high fence around a small yard” of the most critical technologies. Instead of controlling everything, Washington focused on GPUs, advanced memory, lithography equipment, and design software. These were seen as “chokepoints”—narrow but decisive parts of the supply chain where the U.S. and its allies hold near-monopoly positions. This selective denial approach allowed the U.S. to continue exporting mature-node chips to China, keeping economic ties intact while blocking progress in cutting-edge fields.

By 2023 and 2024, controls tightened further. Washington added restrictions on high-bandwidth memory (HBM), advanced packaging equipment, and design software. The Biden administration even proposed a global licensing framework to monitor AI-related computing capacity, while the Trump administration alternately tightened and loosened restrictions depending on broader trade negotiations. Taken together, these steps show how export controls have become not only a national security instrument but also a bargaining chip in diplomacy.

China’s Counterplay: Self-Reliance and Shadow Moves

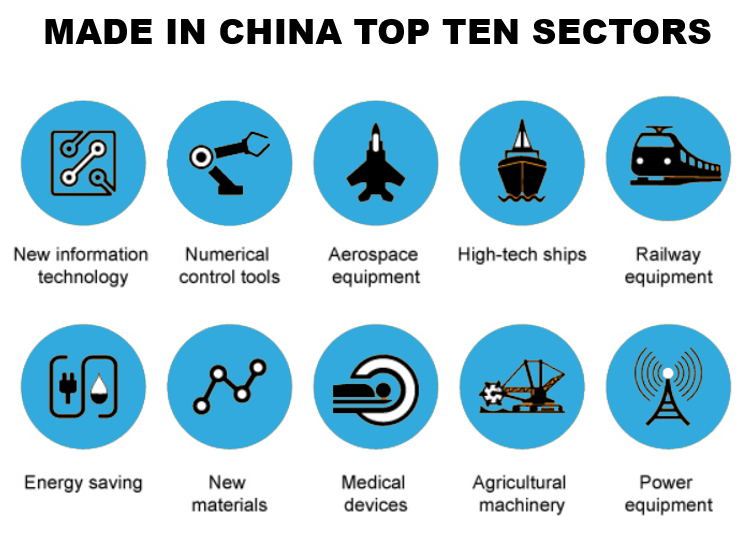

China has responded with its own long-term strategy. Since 2014, Beijing has funneled billions into a state-directed push for semiconductor independence. This industrial policy has relied on subsidies, state-backed financing, and partnerships with foreign firms willing to share technology. The goal, articulated in Made in China 2025, is to build an end-to-end domestic semiconductor ecosystem by 2030, spanning design, fabrication, and advanced packaging.

Yet, faced with U.S. sanctions, Chinese companies have adapted in more immediate ways. Huawei restructured its businesses to create new entities not listed on U.S. sanctions rolls. Memory producer CXMC recalculated technical specifications of its chips to skirt U.S. thresholds. Meanwhile, foundries in Taiwan and other regions have quietly facilitated Chinese designs, sometimes walking the line of U.S. regulations. This cat-and-mouse behavior shows Beijing’s ability to exploit gray zones in the control system.

Equally important, China has launched its own countermeasures. By limiting exports of critical minerals like gallium and germanium, Beijing has reminded Washington that it controls other chokepoints in the global supply chain. It has also used antitrust reviews and regulatory scrutiny to delay or block U.S. semiconductor mergers and acquisitions. These moves underscore that China views semiconductors not just as a market sector, but as a theater of strategic competition.

The Loophole Economy: Nvidia, AMD, and Modified Chips

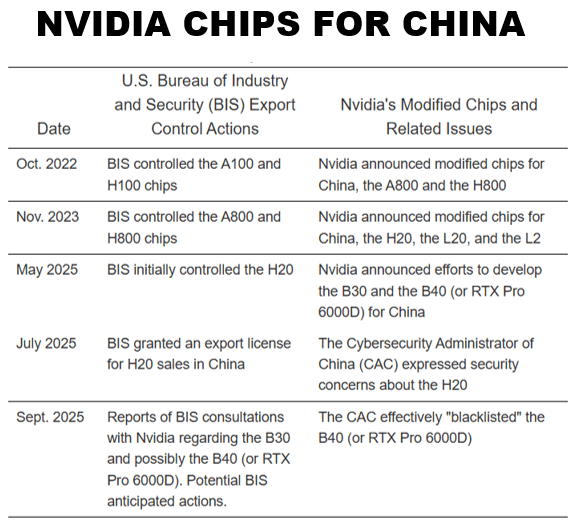

American corporations have also played a central role in shaping the battlefield. Nvidia, the global leader in GPUs, has repeatedly designed “China-only” chips that fall just below U.S. control thresholds. Its A800, H800, and later H20 models are tailored for sale in China, despite U.S. restrictions. While weaker than the unrestricted A100 or H100, these modified chips remain highly capable for AI training and development. AMD has followed a similar path, ensuring continued access to the Chinese market.

This corporate calibration illustrates the difficulty of export controls. Companies face a fundamental conflict: Washington wants to deny China access, but Wall Street demands growth. For Nvidia, China once represented nearly a quarter of its sales. The incentive to design around the rules is therefore immense. In some cases, U.S. regulators have approved such exports with revenue-sharing agreements, raising questions about whether financial interests are eroding the national security rationale.

In October 2022, after BIS controlled its A100 and H100 GPUs, Nvidia customized its A800 and H800 chips for China by reducing the NVLink interface (high-speed, low-latency GPU-to-GPU communication) from 600GB/s to 400GB/s. (PRC firm DeepSeek used the H800 in its AI language model).

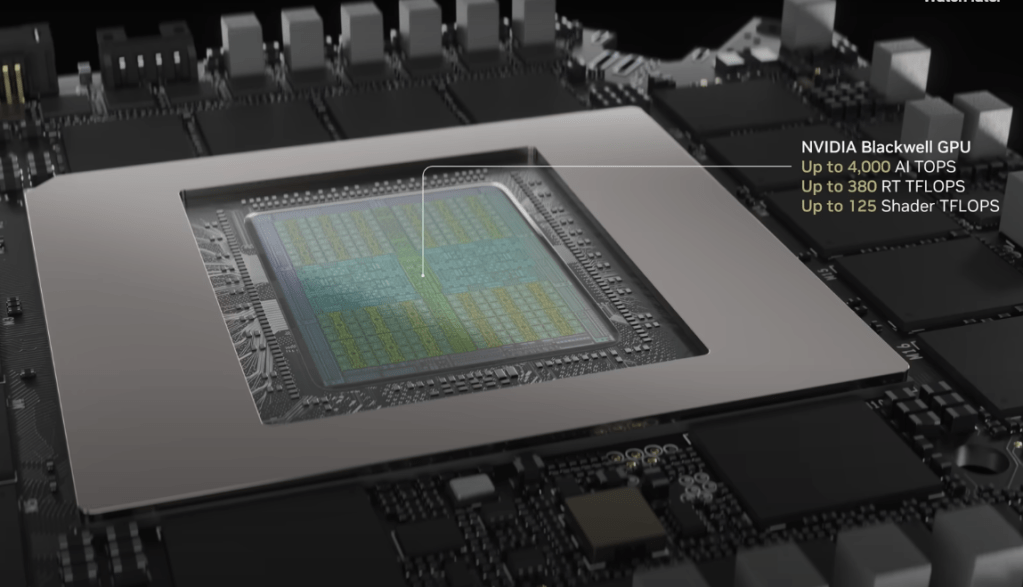

In November 2023, after BIS controlled the A800 and H800 chips, Nvidia announced H20, L20, and L2 chips for China. The H20 is a modified H100 chip that is optimized for AI inference and memory bandwidth. It has a reduced core count but uses HBM3 technology, which BIS restricted in 2024, that supports AI applications. The L20 is a modified AD102 and the L2 is a modified AD104.

In May 2025, after BIS controlled the H20, Nvidia announced a new R&D center in Shanghai and said it would further optimize the H20 and develop the B30 based on its Blackwell RTX Pro with multi-GPU scaling and GDDR7 memory instead of HBM3 (which is subject to BIS controls).

The loophole economy has two consequences. First, it blurs the effectiveness of sanctions, allowing China to maintain access to advanced computing power. Second, it signals to Beijing that restrictions can be gamed with enough persistence. Every new round of controls is met with new corporate innovations, leaving Washington to play regulatory whack-a-mole.

Gaps, Workarounds, and Stockpiles

Despite increasingly elaborate frameworks, U.S. export controls remain imperfect. Many Chinese firms continue to operate outside sanction lists. By creating affiliates or rebranding, they slip through regulatory cracks. Huawei’s spin-off of Honor, which was not sanctioned, allowed the company to maintain relationships with global suppliers. Similarly, some Chinese firms stockpile chips before new rules take effect, ensuring reserves of restricted technology.

Joint ventures and research partnerships further complicate the picture. U.S. and allied companies often establish R&D centers in China, bringing technical expertise that indirectly supports Chinese advances. Licensing rules also contain carve-outs that permit certain dual-use technologies. In practice, these carve-outs allow billions of dollars in exports to flow to blacklisted firms each year. Critics argue that Washington’s regulatory apparatus is always one step behind Beijing’s innovations.

Another challenge lies in enforcement. Export control regimes depend on corporate due diligence and government inspections, but verifying end-use is difficult in China’s opaque system. Some U.S. firms have been caught knowingly or unknowingly supplying restricted technology. In this environment, gaps become not just weaknesses but opportunities for China to accelerate its march toward self-reliance.

NOTE: Our unbiased analysis includes mention of specific semiconductor and AI technology enterprises. All registered trade marks and trade names are the property of the respective owners,

China’s Retaliation: Rare Earths and Regulatory Firepower

China has not simply absorbed U.S. restrictions. Instead, it has weaponized its dominance in critical raw materials. Gallium and germanium exports were restricted in 2023, directly targeting inputs essential for chip manufacturing. Beijing has also hinted at potential limits on rare earth magnets, which are indispensable in both civilian and military technologies. These moves serve as reminders that while Washington dominates high-end design and equipment, China controls the base of the pyramid.

Regulatory firepower adds another dimension. Chinese agencies have delayed or blocked high-profile mergers, such as Nvidia’s attempted acquisition of ARM. They have also placed foreign firms under antitrust investigation, targeting companies like Nvidia for alleged monopolistic practices. At the same time, Beijing requires foreign semiconductor firms to maintain supplies, share technology, and ensure interoperability with Chinese systems as conditions for market access.

The

Middle

East

has

oil . . .

China

has

rare

earths.

These tactics place U.S. firms in a bind. To maintain access to the Chinese market, they must comply with rules that often undermine U.S. export control policy. For example, contractual obligations requiring Nvidia to supply Chinese customers for an entire year effectively enable stockpiling. Such measures reveal Beijing’s strategy: use market leverage and regulatory authority to blunt the impact of sanctions while extracting more technology.

The Congressional Dilemma

Congress now faces a set of difficult policy questions. Should controls be loosened to keep U.S. firms competitive, or tightened to maintain a hard line against China? Loosening could help U.S. companies preserve global market share but risks accelerating China’s technological rise. Tightening may slow China in the short term but could drive Beijing to intensify its push for self-reliance. Both approaches carry strategic and economic costs.

Another contentious issue is the structure of licensing itself. The Commerce Department has, in some cases, approved exports to China in exchange for a share of revenue. This raises constitutional questions about whether the federal government can collect proceeds from trade as part of national security policy. Some lawmakers argue this amounts to negotiating security for profit, while others see it as a pragmatic way to balance economic and strategic interests.

Congress is also considering broader oversight reforms. Proposals include codifying export control rules into law, requiring more frequent reporting from the Commerce Department, and creating whistleblower channels to identify corporate violations. The outcome of these debates will determine whether U.S. export controls are a flexible tool of diplomacy or a permanent architecture of technological containment.

Top Six Take Aways

Export Controls Shape Product Design – Nvidia modified GPUs (A800, H800, H20, L20, L2, B30) specifically to comply with BIS export restrictions while maintaining functionality for the Chinese market.

Performance Trade-offs Are Key – NVLink bandwidth was reduced, core counts lowered, and memory types swapped (HBM3 → GDDR7) to stay within regulatory limits.

Rapid Product Iteration – Nvidia continuously released new versions of GPUs (H20, L20, L2, B30) in response to successive BIS controls, showing agility in product adaptation.

Strategic AI Deployment – Chinese firms like DeepSeek leveraged these modified chips to run AI workloads, highlighting the ongoing demand for high-performance AI hardware despite export restrictions.

Localized R&D Expansion – The opening of Nvidia’s Shanghai R&D center demonstrates a long-term commitment to optimizing chips locally and circumventing certain regulatory hurdles.

Memory & Multi-GPU Architecture Matter – BIS restrictions on advanced memory (HBM3) forced Nvidia to innovate with alternative technologies like GDDR7 and multi-GPU scaling to maintain performance for AI workloads.

Conclusion

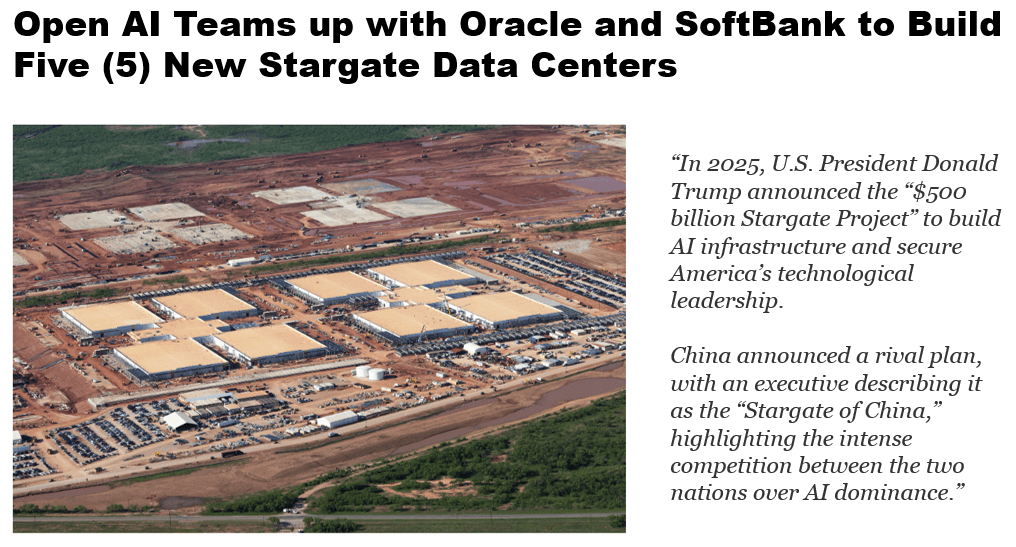

The contest over semiconductors is not simply a trade dispute; it is a structural rivalry over the future of global order. Advanced chips power the tools of artificial intelligence, surveillance, supercomputing, and modern warfare. The side that dominates this domain will shape not only economic growth but also security architectures for decades to come.

The U.S. has so far leveraged its control of chokepoints to slow China’s rise, while China has used state planning, loopholes, and retaliation to keep moving forward. This back-and-forth has produced a technological standoff unlike anything seen since the Cold War. Yet unlike nuclear arms, semiconductors are embedded in civilian life, ensuring that this rivalry touches consumers, corporations, and governments alike.

As the world enters the next decade, the question remains unresolved: will export controls contain China’s ambitions, or will they accelerate Beijing’s determination to go it alone? If silicon is the new oil, then the pipelines of technology—design, fabrication, and supply chains—are now the true battlegrounds of U.S.–China rivalry.

Additional Information

Sources and Image Credits

{1} Made In China | AI Chips in Great Power Competition. Semiconductors are more than microchips; they are the critical infrastructure of modern life. Whoever leads in this domain commands both economic and strategic advantage. Image Credit: PWK International 09/06/2025.

{2} Chips Supply Chain Choke Points. Instead of controlling everything, Washington focused on GPUs, advanced memory, lithography equipment, and design software. These were seen as “chokepoints”—narrow but decisive parts of the supply chain where the U.S. and its allies hold near-monopoly positions. Chart Credit: PWK International 09/24/2025.

{3} Made In China – Top Ten Sectors. Image Credit: Zhamg Ruiqi.

{4} NVIDIA Chips for China. Source and Credit: Britney Nguyen, “Here Are the Chips that Nvidia Can Sell to China,” Quartz, March 27, 2025.

{5} Rare Earth Mines in China. Image Credit: PWK International 09/06/2025.

{6} Broadcom is an American designer and manufacturer of a wide range of semiconductor and infrastructure software products. In the AI ecosystem, Broadcom’s role is crucial but distinct from AI chip designers like NVIDIA. Instead of making general-purpose GPUs, Broadcom focuses on providing the foundational networking and custom silicon that allow massive AI data centers to function efficiently and at scale.

- Custom AI chips (ASICs): Broadcom designs and sells application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) tailored for specific AI workloads. These custom chips are highly efficient for tasks like training, inference, and data processing. Major hyperscale cloud providers such as Google, Meta, and OpenAI are major customers.

- AI networking: The company provides high-performance Ethernet switches that act as the network backbone for large AI clusters, helping to manage the vast amount of data traffic between thousands of servers and GPUs.

- Infrastructure software: Through its acquisition of VMware, Broadcom offers software that helps manage the complex server infrastructure where AI models are deployed.

{7} Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is the world’s largest and most advanced contract chip manufacturer, or “foundry”. TSMC fabricates chips designed by other companies, a “fabless” business model. Its dominance in the AI sector comes from its ability to manufacture the world’s most sophisticated and powerful processors.

- Production of AI chips: TSMC manufactures the advanced AI chips designed by industry leaders like NVIDIA, Broadcom, Apple, and AMD. It is responsible for producing over 90% of the world’s most advanced processors, making it indispensable to the AI revolution.

- Technological leadership: The company has pioneered the use of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography to achieve smaller, more efficient chip designs with denser transistors. These are the high-performance, energy-efficient chips required for advanced AI workloads, such as deep learning and generative AI.

- Scaling production: As the demand for AI grows, TSMC’s immense manufacturing scale allows it to keep up with the global need for advanced AI accelerators.

{8} ASML Holdings is a Dutch company that manufactures the highly complex photolithography equipment needed to produce semiconductors. In the AI supply chain, ASML plays one of the most critical roles by providing the essential tools for chip fabrication.

Foundational role: ASML is several tiers removed from the final AI products, but its unique position makes it an arbiter of technological progress in the AI industry. Companies like TSMC are completely reliant on ASML’s equipment to manufacture the processors that power the AI revolution.

Monopoly on EUV lithography: ASML is the sole producer of Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines. These tools use a specialized form of light to print the microscopic patterns of a chip’s circuits. Without these machines, the world’s most advanced AI chips could not be made.

Enabling Moore’s Law for AI: ASML’s constant innovation in lithography is what allows chipmakers to continue shrinking transistors and packing more computing power into a single chip. The development of High-NA EUV, its next-generation technology, will be crucial for the continued advancement of AI chips.

{9} Our un-biased report includes mention of numerous semiconductor and AI enterprises. All registered trade marks and trade names are the property of the respective owners.

About PWK International

PWK International Advisers provides strategic counsel at the intersection of technology, geopolitics, and the business of government. We help companies and public-sector clients translate emerging capabilities into disciplined acquisition strategies, operational roadmaps, and measurable outcomes. Our analysis blends hands-on government experience with a clear focus on evidence, risk, data driven decisions and competitive advantage.

PWK International provides national security consulting and advisory services to clients including Hedge Funds, Financial Analysts, Investment Bankers, Entrepreneurs, Law Firms, Non-profits, Private Corporations, Technology Startups, Foreign Governments, Embassies & Defense Attaché’s, Humanitarian Aid organizations and more.

From cognitive partnerships, cyber security, data visualization and mission systems engineering, we bring insights from our direct experience with the U.S. Government and recommend bold plans that take calculated risks to deliver winning strategies in the national security and intelligence sector. PWK International – Your Mission, Assured.

Pingback: China in New England |