Assessing Beijing’s Strategic Encirclement of America’s Premier Innovation Ecosystem. From the theft of maritime and autonomy research at elite universities to months-long cyber incursions inside a Massachusetts utility — and a quiet flow of foreign land purchases in Maine — evidence shows Chinese state actors and state-aligned hackers are operating with impunity across New England’s labs, coastlines and utilities.

China in New England: No Longer an Ocean Away

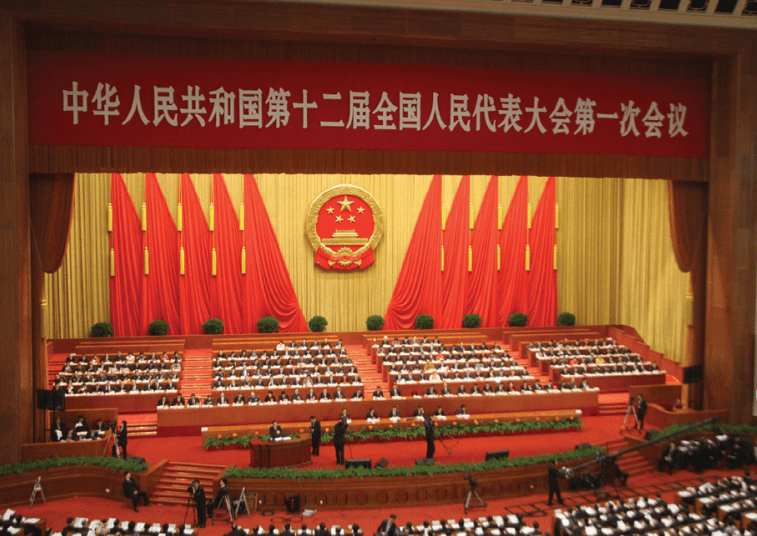

China’s Ministry of State Security is no longer an ocean away — it’s embedded within the fabric of New England’s economy, technology sector, and research institutions. From Cambridge laboratories to Maine’s coastal farmland, Beijing’s agents, proxies, and investors are quietly harvesting the region’s intellectual capital, critical technologies, and strategic resources.

From the corridors of MIT to the control rooms of small New England utilities, from timber holdings in Maine to rural backroads and lab benches — the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and state-aligned Chinese cyber and intelligence actors are quietly building footholds in the region. This 10-minute report will exposé their dirty-handed and grey zone tactics including cyber espionage, academic siphoning, and strategic land acquisition — to illustrate how the “China Strategy” is already at work in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire and Maine.

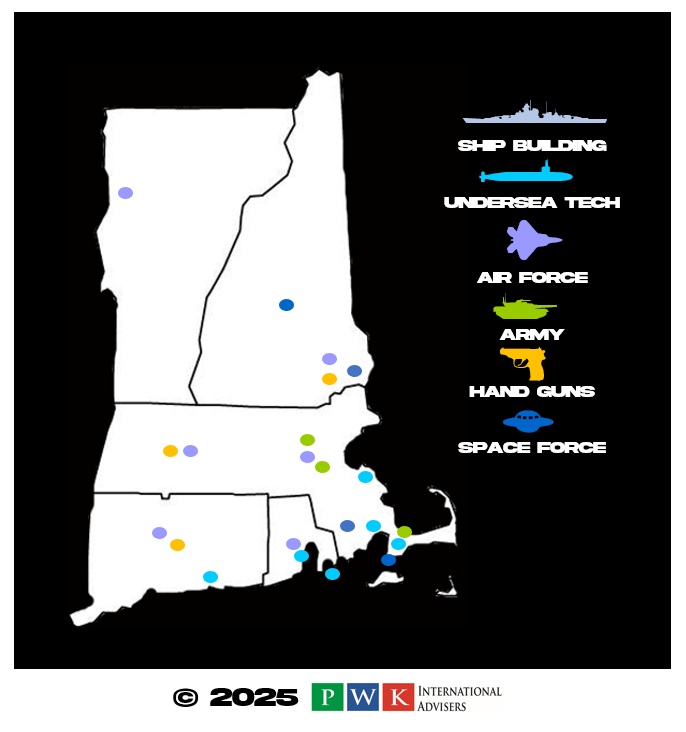

CAPTION: Innovation in New England is driven by a legacy of "Yankee Ingenuity" rooted in a strong academic and industrial history. Today, this spirit continues through a robust eco system that specializes in high-tech fields like biotech, healthcare, aerospace, robotics, small arms manufacturing, under-sea technology and software. Source and Credit: PWK International

This report also unpacks how the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has turned the birthplace of American innovation into an unwitting extension of its own national strategy — exploiting the same openness that once made New England the global center of invention. Drawing on recent arrests, espionage indictments, land acquisitions, and cyber intrusions, this report offers a detailed assessment of how the CCP’s Great Power Competition long game is reshaping the security, supply chains, and sovereign resilience of the northeastern United States.

Background and Context

New England has long been synonymous with American innovation. The region’s universities, research laboratories, and industrial clusters have produced breakthroughs ranging from early computing and microelectronics to autonomous systems and maritime technology. Institutions such as MIT, Harvard, and the University of New Hampshire, alongside federally funded research centers like Lincoln Laboratory and Draper Labs, form a dense ecosystem of knowledge, talent, and critical infrastructure. For adversaries seeking to accelerate their technological capabilities, this ecosystem represents a high-value target — a combination of intellectual property, specialized expertise, and dual-use research that can be leveraged for both civilian and military applications.

The CCP’s strategy in New England leverages both conventional and unconventional vectors of influence. Academically, Chinese students, visiting researchers, and industry collaborators gain access to labs and facilities, sometimes unknowingly serving as conduits for sensitive information. Economically, Chinese investors and proxy entities acquire land, companies, and infrastructure, blending legitimate commercial activity with strategic intent. Geographically, New England’s smaller, dispersed cities and rural areas — from Littleton, Massachusetts to Aroostook County, Maine — offer lower visibility and fewer institutional safeguards compared with major metropolitan hubs, creating opportunities for intelligence gathering, property acquisition, and cyber operations.

Historically, foreign influence in New England has been subtle but persistent. In the 1990s and early 2000s, export control violations were identified in defense-related manufacturing, particularly in maritime and aerospace sectors. More recently, arrests and indictments have revealed coordinated attempts by Chinese nationals and CCP-aligned entities to acquire undersea warfare technology, sensitive industrial designs, and high-tech manufacturing know-how from local contractors and universities. Cybersecurity breaches targeting research networks, supply chain management systems, and municipal utilities underscore the CCP’s willingness to blend traditional espionage with modern digital capabilities.

The region’s concentration of dual-use technology — research that can be applied to both civilian and military purposes — makes it uniquely attractive. Autonomous systems, robotics, advanced sensors, and maritime platforms developed in Cambridge or at Lincoln Laboratory may have direct applications for naval modernization programs in the Indo-Pacific and elsewhere. Simultaneously, New England’s abundant rural land, accessible waterways, and lightly regulated local governance provide avenues for money laundering, clandestine property acquisitions, and the establishment of front organizations. Collectively, these activities form a mosaic of influence that the CCP can exploit without triggering widespread attention or national scrutiny.

From a strategic perspective, New England represents a microcosm of the broader challenge facing the United States: how to maintain an open and innovative society while protecting intellectual property, critical infrastructure, and national security. The region’s universities, startups, and small-to-medium enterprises are often on the cutting edge of research yet lack the robust compliance and counterintelligence infrastructure found in larger defense contractors or government labs. This combination of high-value innovation, geographic dispersion, and local governance gaps creates an environment ripe for exploitation.

In this report, we analyze specific cases illustrating the CCP’s quiet infiltration, assess the vectors of influence and risk, and map the geographic and institutional nodes of concern. From MIT’s laboratories to Maine’s coastal towns, New England has become both a repository of advanced knowledge and a target-rich environment.

The Ministry of State Security

China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) operates as both an intelligence service and a geopolitical instrument, blending cyber operations, human intelligence, and economic leverage into a unified strategy. In New England, these methods converge in ways that reflect the MSS’s broader global playbook—a slow, adaptive, and multidimensional campaign to secure access, influence, and information. The region’s unique combination of advanced research institutions, maritime industries, and rural land holdings creates an ecosystem that is both technologically sophisticated and logistically porous—an ideal environment for strategic infiltration.

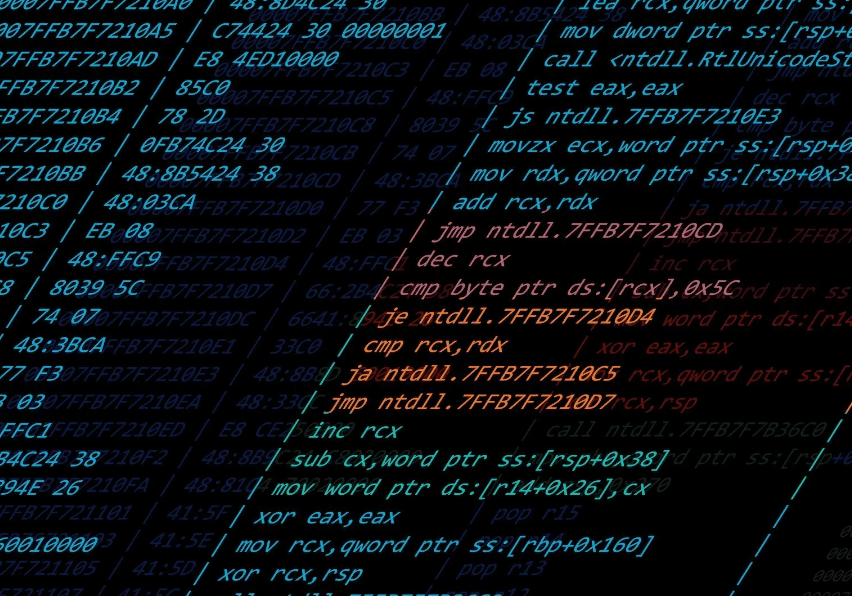

The cyber dimension represents the most visible and technically complex layer of MSS operations. Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups such as Volt Typhoon exemplify how Beijing’s cyber apparatus targets critical infrastructure through sustained intrusion campaigns. Their objective is not immediate disruption but long-term access: establishing footholds within IT systems, expanding laterally into operational technology networks, and maintaining dormant control until strategic conditions demand activation. Even when detected, these intrusions achieve secondary effects by exhausting defenders, eroding public confidence, and normalizing the sense of vulnerability across targeted sectors. (see: Best Practices in Cyber Security of Weapon Systems)

The human and academic domains offer subtler but equally potent entry points. Through research collaborations, exchange programs, and university partnerships, the MSS and affiliated entities exploit legitimate channels of scientific cooperation to obtain sensitive intellectual property. Researchers and diaspora professionals may be cultivated or coerced into providing access, while joint laboratories and funding initiatives mask the true purpose of data collection. Such operations thrive in open academic environments like New England’s, where transparency and internationalism coexist with high-value innovation.

Economic infiltration provides the final layer of the MSS’s regional strategy. By acquiring land, leasing resource rights, or investing in local ventures such as timber, energy, and maritime infrastructure, state-linked entities secure both physical presence and political capital. These ties create latent influence networks that can be activated when needed—often under the cover of normal business activity. The use of shell companies and domestic intermediaries ensures layered deniability, enabling Beijing to benefit from proximity and access while disavowing direct involvement. Together, these cyber, human, and corporate tactics make New England a soft flank in America’s defensive posture—a place where patient adversaries can quietly prepare the terrain for future advantage.

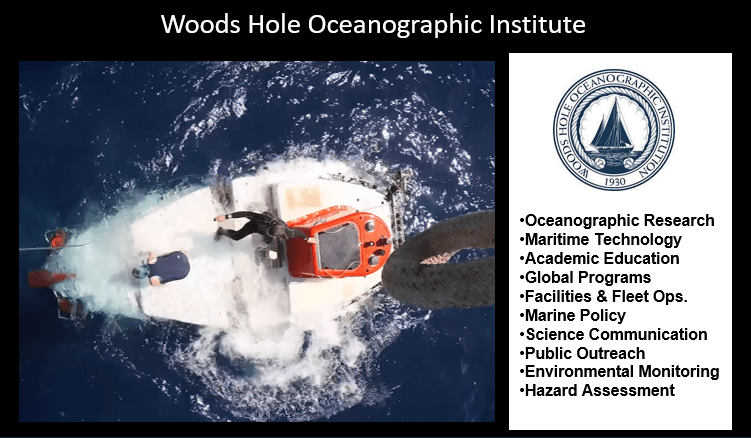

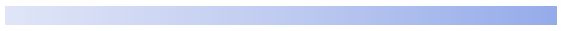

Academic Espionage: MIT and the Maritime Frontier

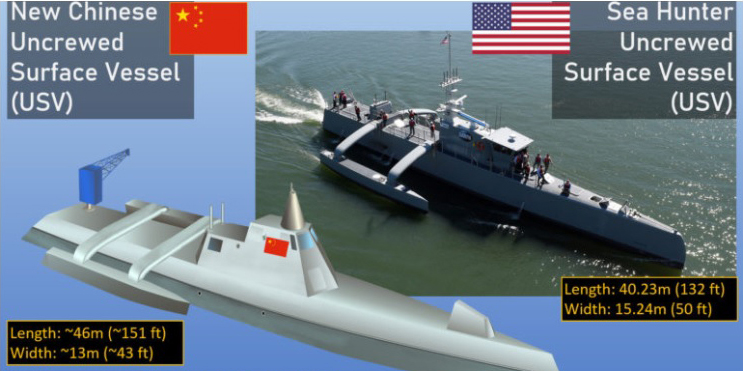

In early 2019, MIT and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution were named among more than two dozen U.S. universities targeted by Chinese‐linked hackers in what investigative reporting described as a coordinated push to steal maritime technology. These reports allege that the intrusions aimed at capturing sensitive research in underwater robotics, marine sensors, and autonomy systems—components potentially useful for anti-submarine warfare and naval surveillance. Woods Hole officials stated that they had found no confirmed breach, but the WSJ and other outlets emphasized that the pattern of targeting revealed the CCP’s interest in cutting-edge maritime innovation on Cape Cod and Cambridge.

Another well-documented case is the 2018 indictment of Shuren Qin, a Chinese national living in Massachusetts, who operated a company called LinkOcean Technologies. According to DOJ filings, Qin and his associates conspired with affiliates of the People’s Liberation Army to illegally export goods with underwater and marine applications—including hydrophones, unmanned underwater vehicles, side-scan sonar systems, and remotely-operated vessels—to China’s Northwestern Polytechnical University (NWPU), a PLA-affiliated institute. These exports occurred from mid-2015 to late 2016, evading U.S. export controls and misleading customs and border authorities.

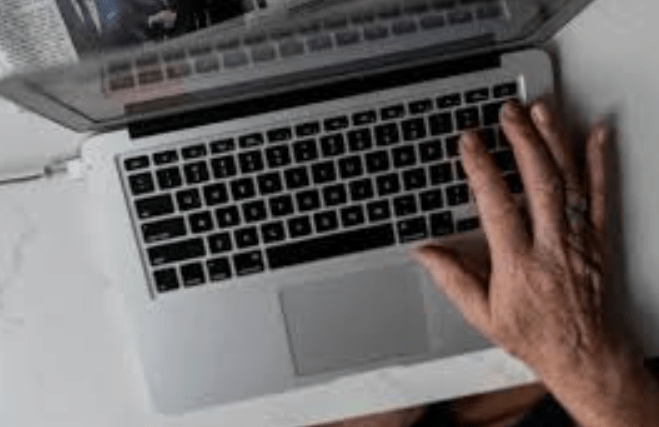

The PLA’s strategic doctrine, especially its “Blue Ocean Information Warfare” (蓝海信息战) concept, views maritime robotics, autonomy, and underwater navigation as vital enablers of sea control, persistent surveillance, and anti-access area denial (A2AD) capabilities. Unmanned surface vessels, undersea sensors, and autonomous navigation platforms allow China to monitor submarine movement, map undersea terrain, and extend its reach into contested waters—all without risking conventional naval assets. Entities like MIT and Woods Hole, which conduct dual-use research in these domains, are therefore prime targets for theft or influence, and what may appear as academic openness can be leveraged into military advantage under China’s doctrine of asymmetric, intelligence-first warfare.

University Targeting & Maritime Research Theft

A widely cited analysis documented how Chinese hackers targeted 27 U.S. universities to steal maritime research and related intellectual property, including from institutions with strong naval and ocean engineering programs.

Though not always named, MIT has been publicly scrutinized in multiple academic-foreign ties investigations (e.g. in faculty disclosure cases) and is often understood to be in the crosshairs of espionage and industrial tech transfer pressures.

The Department of Justice, through its earlier “China Initiative” era, prosecuted (or sought to prosecute) several cases of undisclosed foreign funding or concealment of links to Chinese institutions — specifically in science and engineering domains

The risk vector is not only malicious hacking: it includes co-opted faculty, hiring or sponsoring visiting scholars, joint labs, or funding that imposes covert IP ownership expectations.

Once inside the research network, an actor could triangulate other cutting-edge projects (e.g. unmanned surface vessels, autonomous navigation algorithms) that the university’s tech-transfer or spinout arms did not fully secure.

Undetected for Ten (10) Months

In late 2023, officials at Littleton Electric Light & Water Department (LELWD) — a modest municipal utility serving Littleton and Boxborough, Massachusetts — received a rare Friday afternoon call from the FBI. The message: a Chinese cyber espionage group, linked to the “Volt Typhoon” campaign, had penetrated their systems and was undetected for months. Within a week, CISA and the FBI were on site, and LELWD entered a protracted remediation and forensics cycle.¹

The Littleton case should sound every alarm: if a small utility in the Boston suburban apple orchards can be infiltrated for nearly a year, so too can far more consequential systems across New England.

This was not a flash intrusion; subsequent reporting and internal documentation showed that the hackers had been inside LELWD’s network since February 2023 — nearly 300 to 300+ days before discovery. They had access not just to peripheral IT systems but to operational technology (OT) infrastructure (file servers, network maps), albeit without evidence of direct control over the physical electrical grid.

Land and Resource Acquisitions in Maine

Beyond cyber and academic intrusion, the CCP and aligned actors project influence through real estate and resource control—particularly in regions with natural assets and low regulatory scrutiny. Among U.S. states, Maine is a standout: it ranks second in total acreage of foreign-owned agricultural land, and by proportion, it leads the nation, with over 21.1 % of privately held agricultural land under foreign control. Though Canadian entities hold the lion’s share—approximately 2.9 million acres—Dutch, German, U.K., and “other” foreign investors also hold significant parcels. While Chinese ownership remains a minor fraction (less than 1 % of all foreign-held U.S. acreage), the concern is not scale alone but strategic placement—waterfront access, forested tracts, and remote parcels that can serve deeper operational or influence functions.

More than 3.5 million agricultural acres of Maine land is owned by foreign interests, more than any of the other 50 states. Illegal, Chinese-organized crime-linked marijuana growing operations have been a major issue in Franklin, Kennebec, Lincoln, Oxford and Aroostook Counties.

The strategic risks posed by these land holdings are unsettling. Properties near rivers, lakes, and coastal points may serve as discreet staging grounds for maritime research, underwater sensor installations, or small docking facilities. Timber lands and forest ecosystems hold economic and ecological leverage—control over water, wood supply, and local communities. In many areas, oversight is weak: deed offices are understaffed, conservation trusts may not rigorously vet buyer origin, and county-level regulation offers limited transparency. In that context, even modest acquisitions may carry outsize strategic value.

Federal and state actors have begun to respond. Senate hearings have flagged foreign farmland ownership as a national security issue, citing risks tied to adversarial checks on domestic supply chains, stealth influence, and latent intrusion infrastructure. Some state legislatures and local agencies are now proposing tighter screening of foreign purchases near critical resources—especially by nations designated as strategic competitors. While Chinese acquisitions in Maine are not yet pervasive, the state’s structural exposure means that future infiltration under cover of economic investment is a credible threat.

The Balloon That Broke the Illusion

In early 2023, Americans looked up. A high-altitude Chinese balloon drifted across the continental United States, crossing nuclear missile fields and military bases before being shot down off the South Carolina coast. It wasn’t the only one. The incident ignited headlines, congressional hearings, and a sudden national awareness that China’s intelligence collection was not confined to satellites or cyberspace — it was literally floating overhead in the stratospheric seam in our national defenses. What many missed, however, was that this was merely the visible symptom of a far broader campaign already anchored deep inside the nation’s communications infrastructure and services providers.

While the balloon became a meme, the real surveillance vectors were — and remain — prolific: mobile phones, apps, network components, and IoT devices built in, coded by, or dependent on Chinese supply chains and over the air firmware updates. Intelligence assessments since have confirmed what many suspected: China’s access to American data flows through our citizens as much as MSS espionage targeting the military. From firmware backdoors to data harvesting via popular consumer platforms like iPhones, Amazon Alexa and Bluetooth enabled smart TV’s, the country’s technical footprint gives china visibility into billions of U.S. financial transactions and telephone conversations every day.

The irony in our editors cartoon above suggests that even our attempts to celebrate victory over Chinese aggression and espionage are powered by Chinese-made hardware and state owned or proxy controlled delivery services. The balloons, like the phones in our pockets, reveal the same paradox — that the tools of modern life double as the conduits of adversarial surveillance, dirty handed influence and worse.

“The greatest long-term threat to our nation’s ideas, our economic security and our national security is that posed by the Chinese Communist government … they will stop at nothing to steal what they can’t create.”

FBI Director Christopher Wray

Undersea Technology Exports

Wellesley MA

Shuren Qin, a Chinese national, used his Massachusetts-based company, LinkOcean Technologies, to export undersea warfare components to the PLA-linked Northwestern Polytechnical University.

United Technologies Document Theft Hartford Connecticut

A Chinese citizen was convicted of stealing sensitive documents related to military programs from United Technologies’ aerospace division, transferring critical intellectual property to PRC networks.

Electronics Export Scheme

Waltham MA

Chitron Electronics exported restricted radar and electronic warfare components to China via U.S. proxies, circumventing federal export controls.

MITRE NERVE Network Breach

Bedford MA

In 2024, Chinese state-linked actors exploited zero-day vulnerabilities in MITRE’s NERVE research network, bypassing multi-factor authentication to access collaborative R&D environments.

Volt Typhoon Cyber Attacks

Maine

Seven Chinese nationals were indicted for cyber intrusions against U.S. businesses and critics of CCP policy in Maine, associated with the Volt Typhoon advanced persistent threat group

Unauthorized Technical Exports Cambridge MA

Academic startups and small firms in Cambridge have exported defense-related technical data to foreign manufacturers without a license, highlighting vulnerabilities in the oversight of dual-use research.

ITAR Export Violation

North Andover MA

A Chinese researcher gained unauthorized access to ITAR-controlled antenna designs at Microwave Engineering Corp.

What is Considered An Act of War?

The People’s Republic of China has quietly expanded its offensive cyber operations against the United States, targeting not just federal networks or major defense contractors, but the smallest nodes of the nation’s critical infrastructure. Over the past two years, Chinese state-backed hackers—operating under the direction of the People’s Liberation Army and the Ministry of State Security—have attempted or succeeded in breaching more than 200 critical infrastructure systems, from energy grids to water treatment facilities. Even the town of Littleton, Massachusetts, found itself in the crosshairs, a reminder that scale offers no protection in the digital battlespace. The attacks are not random intrusions; they represent deliberate reconnaissance and systems-mapping activity—an early stage of warfare conducted through code instead of conventional arms.

These incursions are not mere espionage—they are hostile acts designed to test resilience, identify vulnerabilities, and prepare the battlefield for disruption. History shows that nations do not probe the infrastructure of others without intent. Whether through cyber exploits, compromised hardware, surveillance systems, or coordinated influence campaigns, Beijing’s digital advance across America’s networks mirrors its physical expansion across the Indo-Pacific. The pattern is unmistakable: this is pre-conflict maneuvering. New England’s municipalities, laboratories, and industries—no matter how small—are now on the front line of a slow, methodical campaign to erode American security from within.

Conclusion.

The CCP’s activity in New England — from Cambridge research labs to rural Maine properties and municipal networks — demonstrates a sophisticated, multi-domain approach to strategic infiltration. Across academic, commercial, and cyber vectors, Beijing leverages the openness of U.S. institutions to acquire dual-use technologies, exert economic influence, and gain footholds near critical infrastructure. The cumulative effect of these operations is subtle yet systemic, creating risks for national security, the U.S. economy, and the integrity of critical technology supply chains.

For investors, policymakers, and security professionals, the lesson is unmistakable: the map of national power now runs through places once considered peripheral.

The next conflict may not begin with a missile launch or naval blockade, but with a lab partnership, a land deed, or a lingering network credential.

This is the next frontier of influence — not in the open, but woven into the infrastructure and institutions of our campuses, towns, and forests. For readers in intelligence, policy, and finance, the New England theater may soon yield more than just academic curiosity: it may reveal the future fault lines of Chinese strategic aggression and infiltration in America.

Additional Information

Acknowledgements, Sources and Image Credits

{1} China in New England | Assessing Beijing’s Strategic Encirclement of America’s Premier Innovation Ecosystem. An Expert Network Report by PWK International Managing Director David E. Tashji. 10/17/2025. (C) 2025 PWK International.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, or academic work, or as otherwise permitted by applicable copyright law.

“China in New England” and all associated content, including but not limited to the report title, cover design, internal design, maps, engineering drawings, infographics and chapter structure are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use, adaptation, translation, or distribution of this work, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.

This report is a work of non-fiction based on publicly available information, expert interviews, and independent analysis. While every effort has been made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any employer, client, or affiliated organization.

All company names, product names, and trademarks mentioned in this report are the property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. No endorsement by, or affiliation with, any third party is implied.

{2} The Department of War in New England. Infographic credit: PWK International 10/15/2025

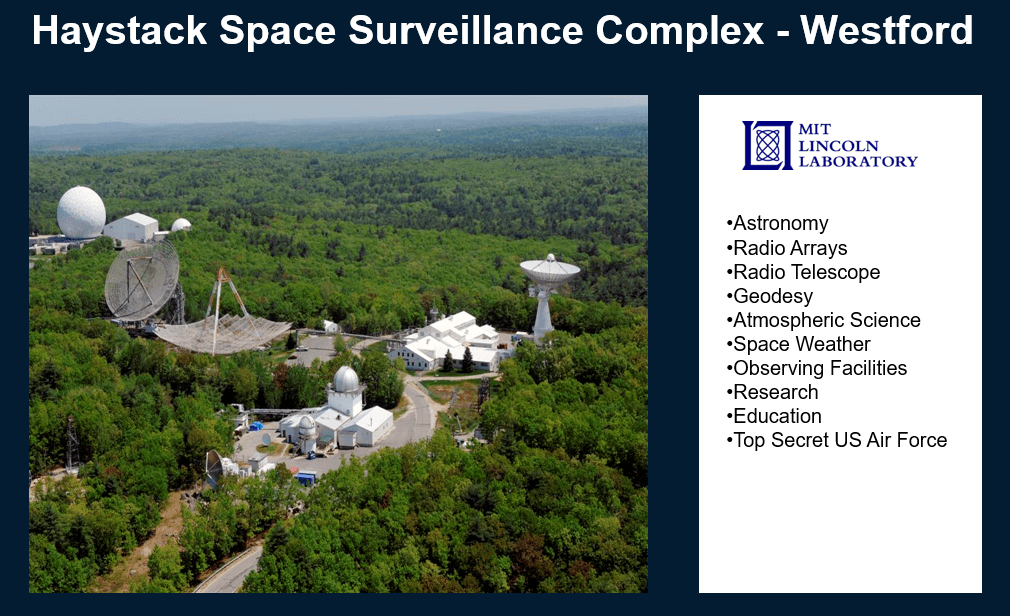

{3} The Westford Haystack Observatory, located northwest of Boston, is one of the most sophisticated radar and radio science facilities in the United States, operated by MIT under contract with the Department of War. Originally established during the Cold War for space surveillance and missile tracking, Haystack now supports national security missions including space domain awareness, deep-space imaging, and satellite characterization for the U.S. Space Force and Intelligence Community. Its massive, high-precision radar and 37-meter antenna array can detect and track objects tens of thousands of miles away, providing critical data on orbital debris, foreign satellites, and hypersonic vehicle testing. Quietly nestled in the Massachusetts countryside, Haystack remains a cornerstone of America’s strategic eyes in space — and an enduring symbol of how advanced research facilities underpin the nation’s defense infrastructure.

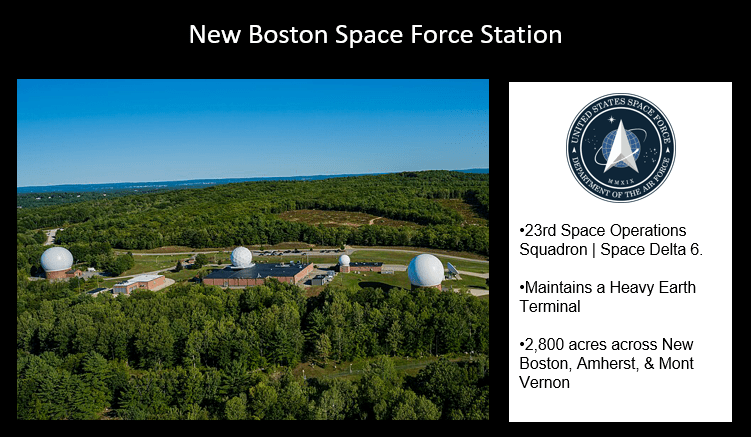

{4} The New Boston Space Force Station, located in New Hampshire serves as a pivotal node in the United States’ global space surveillance network. Established in 1959 as a radar tracking site and now operated by Space Delta 6 under U.S. Space Command, the base provides around-the-clock satellite control, telemetry, and data relay services that underpin modern military and intelligence operations. Its ground antennas maintain contact with Department of War and allied satellites, ensuring secure communication links and situational awareness across orbital domains. Once a Cold War outpost hidden in the forests of New England, New Boston has evolved into a digital command hub — quietly monitoring the heavens for threats, anomalies, and opportunities in the contested space domain.

{5} The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), located on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, is the world’s leading center for ocean science, engineering, and exploration — and a critical research partner to the U.S. Navy and intelligence community. Founded in 1930, WHOI develops advanced undersea vehicles, sensors, and autonomous maritime systems that map, monitor, and secure the global ocean. Its researchers pioneer technologies in deep-sea robotics, acoustic surveillance, and unmanned submersibles — capabilities vital to anti-submarine warfare, seabed infrastructure protection, and environmental intelligence. From discovering the wreck of the Titanic to advancing classified undersea navigation tools, Woods Hole remains at the frontier where scientific innovation meets national security, defining the maritime edge of American technological dominance.

{6} A nuclear-powered Type 094A Jin-class ballistic missile submarine of the PLA Navy takes part in a military display in the South China Sea. Photo: Handout via Reuters

{7} “Volt Typhoon hackers were in Massachusetts utility’s systems for 10 months” — The Record The Record from Recorded Future

{8} Dragos details LELWD’s fight … over 300-day OT network breach” Industrial Cyber

{9} LELWD published case study “Foreign Hackers Targeting US Utilities” (LELWD PDF) Lelwd

{10} NJCCIC “Volt Typhoon – China-linked campaign” Cyber NJ

{11} Dark Reading “Volt Typhoon Strikes Massachusetts Power Utility” Dark Reading

{12} Fortune / other coverage of Chinese targeting of U.S. maritime research (university hack cases) (source as summary) The Record from Recorded Future

{13} Foreign ownership in U.S. ag land (USDA / AFIDA) — 43.4 million acres held by foreign persons in 2022 Farm Service Agency

{14} 3.5 Million Acres of Maine Land Owned by Foreign Interests” — MaineWire reporting The Maine Wire

{15} CSIS “Foreign Purchases of U.S. Agricultural Land” analysis csis.org

{16} Senate hearings on foreign farmland ownership, testimony about China as national security risk mainemorningstar.com

{17} Global Affairs blog on how much U.S. land China owns (<1 % of foreign-held) globalaffairs.org

{18} WBUR / Wall Street Journal reporting: “MIT and more than two dozen universities have been targeted by Chinese hackers …’” in pursuit of maritime military secrets via collaboration with Woods Hole. (2019) WBUR

{19} DOJ, District of Massachusetts press release: “Chinese National Allegedly Exported Devices with Military Applications to China” — Shuren Qin / LinkOcean Technologies export case. Department of Justice

{20} US Navy Sea Hunter comparison drawing by H I Sutton 2020. Copyright H I Sutton

{21} High-altitude balloons are extremely difficult to detect. A 2005 study by the U.S. Air Force’s Air University states surveillance balloons often present very small radar cross-sections, “on the order of hundredths of a square meter, about the same as a small bird”, and essentially no infrared signature, which complicates the use of anti-aircraft weapons.

In early February 2023, a high-altitude balloon, launched from China, drifted across North America—entering U.S. airspace over Alaska before traversing the continental United States and ultimately being shot down over territorial waters near South Carolina on February 4. Wikipedia+2U.S. Department of War+2 The U.S. military, acting on President Joe Biden’s directive, delayed the strike until the balloon was safely over water so that falling debris would not endanger civilians. U.S. Department of War+1 The balloon carried a large payload—described by U.S. officials as equivalent to “two boxcars” of surveillance equipment. Wikipedia+1

Despite the spectacle of the shoot-down, official analysis suggests the device did not transmit data back to China while floating over the United States. ABC News+1 However, forensic examination revealed U.S.-made components—including sensors and satellite-communication modules—inside the balloon’s payload, raising critical concerns about how commercially available American technology can end up aiding foreign intelligence collection. FOX 10 Phoenix+1 The incident signalled that China’s intrusions are not limited to cyber networks, but also embed themselves physically in the sky and in our supply chains.

The Balloon Episode serves as a concrete metaphor for the broader challenge at hand: omnipresent yet under-the-radar. As our [dark humor] editors cartoon underscores, even the devices and systems we use to spy on foreign powers might themselves be built by or dependent on those same powers. The real front line is not the balloon we see—it’s the network we don’t. And it is already woven into the mobile phones and over the air firmware update devices and infrastructure of our everyday lives.

NOTICE | Our un-biased report includes mention of numerous educational institutions, research labs, military units, ocean research institutes, non-profits and dual use innovators and disruptors. All registered trade marks and trade names are the property of the respective owners.

About PWK International.

PWK International provides national security and technology advisory services to clients navigating the intersection of innovation, intelligence, and global competition. Our firm delivers strategic insight on defense modernization, advanced research ecosystems, and the shifting dynamics of U.S.–China technological rivalry. Through our reporting and consulting practice, we translate complex geopolitical and technical developments into actionable intelligence for decision-makers.

We serve a broad range of clients — including hedge funds, defense contractors, technology startups, and public-sector leaders — who require clarity on how emerging threats and opportunities are reshaping the business of government. Our expertise spans defense acquisition reform, autonomous systems, AI-driven surveillance, and the economics of innovation, helping clients position themselves strategically in an era defined by uncertainty and accelerated change.

China in New England reflects PWK International’s continuing mission: to expose the subtle architectures of influence that shape American power and policy. From critical infrastructure vulnerabilities to the flow of intellectual capital through New England’s research corridors, our work seeks to illuminate where national security, commerce, and technology converge — and what it will take to defend them.

Pingback: China in New Mexico |

Pingback: China in Silicon Valley |