China’s Ministry of State Security is no longer an ocean away. It has quietly infiltrated into America’s high deserts — the vast, remote expanses of New Mexico, Nevada and Arizona — where the nation’s most advanced science, weaponry, and space systems are born. From the high-security corridors of Sandia and Los Alamos National Laboratories to the desert test ranges of White Sands and the orbit-tracking arrays of Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, this is ground zero for the next chapter of great-power competition in the sciences.

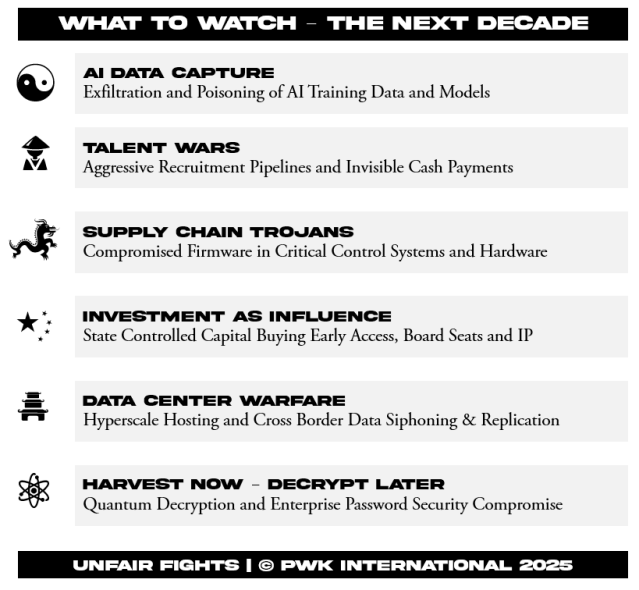

This report will unpack how Beijing is embedding itself into the “science war” of the American Southwest. It will trace how Chinese talent-recruitment programs, academic partnerships, state funded corporate investment, phony front businesses, narcotics trafficking rings, persistent cyber operations and dirty handed influence operations are converging on the region’s labs, test sites and infrastructure. Based on recent arrests, export-control prosecutions, critical-infrastructure intrusions, and real-estate acquisitions, we will map how the desert is actually a treasure map of high value applied research and scientific discovery and a prime target of the Chinese Ministry of State Security and their asymmetric, intel first Great Power Competition long game.

This report offers an assessment of the broader architecture of influence: dual-use research in New Mexico feeding into China’s missile and quantum ambitions; Nevada’s mineral and energy corridors being shaped by state controlled foreign capital; and unclassified networks at national labs leveraged as proxies for breakthrough weapons modeling.

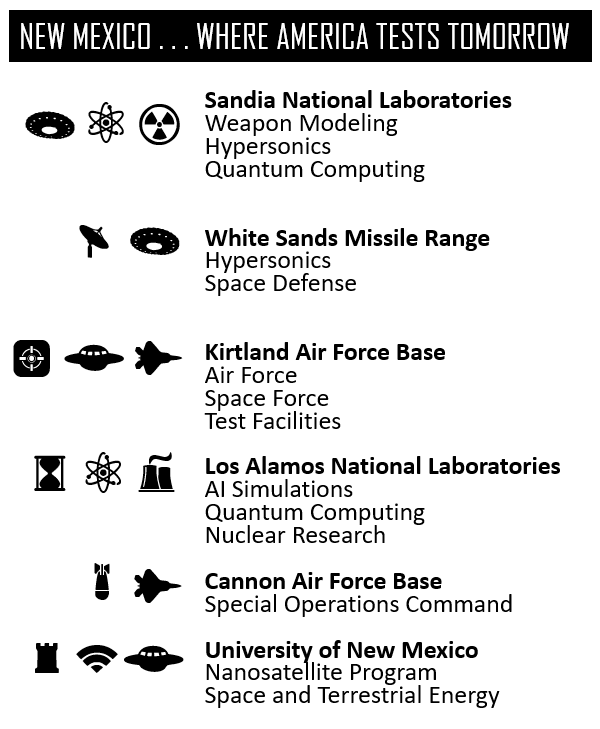

NEW MEXICO - A TREASURE MAP OF WORLD LEADING SCIENCE

The American Southwest has always been a proving ground — It was here that the United States built the bomb, launched its first missiles, and engineered the apparatus to monitor and explore the frontiers of space. Today, those same deserts are home to a quieter struggle — one waged not with detonations, but with data.

Drive past the barbed perimeter of Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, or through the mountain-ringed silence surrounding Los Alamos, and you feel history humming beneath the sand. These are not just labs — they are temples of American deterrence, places where the invisible architecture of power is built in code, quantum processors, and directed-energy beams. Yet the same global networks that make innovation possible — university partnerships, joint research projects, digital collaboration — have become potential conduits for strategic compromise.

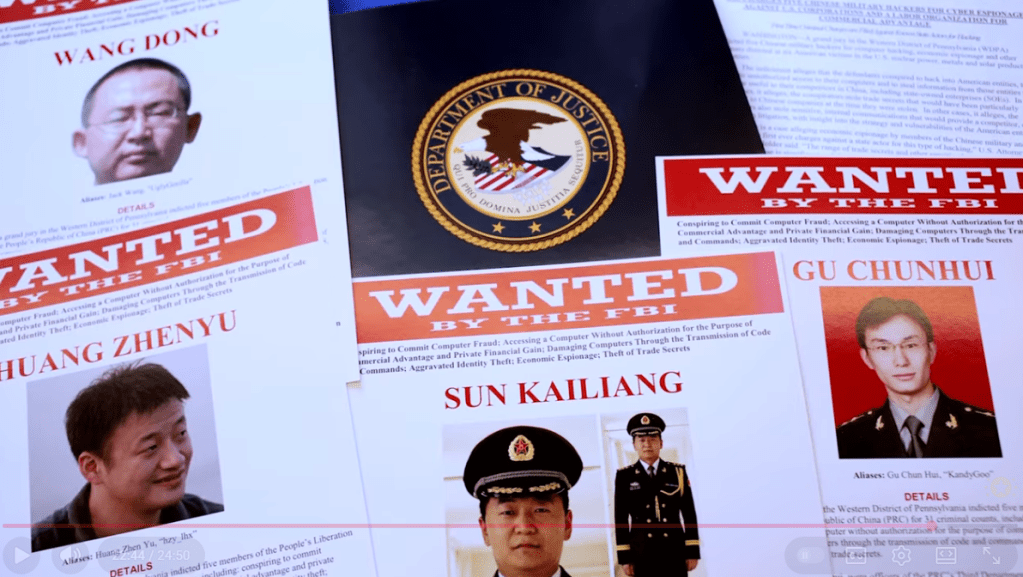

Over the last decade, the Department of Energy’s National Laboratories have faced an uncomfortable reality: that foreign intelligence services, particularly from the People’s Republic of China, are increasingly targeting their researchers, contractors, and even the third-party vendors supporting their systems. The FBI’s counterintelligence teams have documented cases of data exfiltration, ghost funding, and intellectual property transfers masked as academic exchange. The problem is no longer isolated — it’s systemic, and not just in New Mexico.

At Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, the focus on AI-enhanced simulation and laser fusion makes it one of the most data-rich environments on the planet. At Sandia, hypersonic weapon models are fed into cloud environments that mirror classified infrastructure — creating an irresistible target for espionage. Even the surrounding universities — from the University of Arizona’s optical sciences programs to New Mexico Tech’s cybersecurity labs — have become feeder nodes in an ecosystem where openness and outright theft are in constant tension.

The Southwest represents the kinetic frontier — where scientific concepts become deployable weapon systems. China understands this geography intimately. Through academic partnerships, investment in regional technology startups, and cyber intrusions mapped by the DOE’s Inspector General, the Southwest has become a new theater in what one intelligence official called “the science war of the century.”

The tactics are rarely cinematic. There are no desert meetups or briefcases full of blueprints. Instead, it’s the slow siphoning of knowledge through dual-use research agreements, joint conference papers, and remote collaborations hosted on shared cloud platforms. The 2023 DOJ case against a visiting Chinese researcher at Los Alamos revealed how sensitive data on advanced battery technologies — key to hypersonic propulsion — was quietly funneled back to companies linked to the Chinese Academy of Sciences. It’s a case that barely made headlines, but it symbolizes a broader shift: the espionage battlefield is now embedded in America’s open science infrastructure.

Oppenheimer chose Los Alamos because it was a remote and isolated mesa in New Mexico that he was familiar with, and the site offered the necessary security and seclusion for the top-secret Manhattan Project. Image Credit: Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Out at White Sands Missile Range, the horizon stretches for miles, punctuated only by the occasional contrail of an experimental test. Here, the United States develops its hypersonic interceptors and space-based tracking systems. Yet many of the software models underpinning these programs rely on research performed at semi-open institutions — including DOE-unclassified computing nodes that are accessible to cleared foreign nationals under joint agreements. It’s a paradox at the heart of American innovation: to remain ahead, the U.S. must collaborate; but to collaborate, it must expose its edge.

The Southwest is also where the private defense sector has quietly fused with public research. Companies like Honeywell Aerospace, Raytheon, and Lockheed Martin’s Advanced Technology Center maintain deep research ties to regional labs and universities. These collaborations, essential for accelerating new technologies, also widen the aperture of vulnerability. The Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS) doesn’t need to steal directly from the labs — it can infiltrate the periphery, targeting subcontractors, academic partners, or even visiting scholars with access to unclassified but strategically meaningful data.

What’s happening in the American desert is not just another spy story — it’s a test of whether the United States can protect its innovation core without strangling it. For decades, openness was the advantage: the ability to draw the world’s brightest minds into American research institutions. Now that very openness has become the Achilles’ heel of deterrence.

If China in New England revealed a competition unfolding across ivy league universities, under sea technology institutes and biotech corridors, China in the Southwest exposes a deeper contest — one for the intellectual sovereignty of American science itself. The future of deterrence won’t be decided by who builds more ships or missiles, but by who controls the invisible knowledge pipelines that connect code to gaining the technological upper hand.

Kirtland Air Force Base is a key military installation in New Mexico, located in the southeast quadrant of Albuquerque and sharing runways with the city's international airport. It is one of the largest Air Force bases in the country, occupying over 51,500 acres. Image Credit: US Air Force.

National Laboratories as Targets

In 2023, federal prosecutors charged Los Alamos scientist Zhao Yanjun, a Chinese national and participant in the Thousand Talents Program, with conspiring to transmit sensitive battery research to institutions in China. His case was part of a broader DOJ initiative — the China Initiative, later restructured but still active through ongoing counterintelligence work — that exposed dozens of recruitment efforts targeting researchers tied to U.S. defense and energy programs. Investigators determined that much of the intellectual property exfiltrated from DOE-linked labs was dual-use in nature: advanced materials for energy storage, semiconductors, and aerospace components applicable to next-generation military platforms.

Beyond personnel, cyber operations remain the MSS’s most consistent and deniable tool. Multiple Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) groups linked to Chinese state interests — including APT31, APT41, and Volt Typhoon — have conducted persistent reconnaissance of networks associated with the national labs. In several documented cases, hackers exploited unclassified research networks, contractor VPNs, or academic partnerships to establish beachheads for long-term data collection. While U.S. counterintelligence agencies emphasize that classified systems remain secure, the loss of unclassified modeling data, algorithms, and sensor research may offer China a crucial “shortcut” in reverse engineering and simulation — a digital mirror of what the Manhattan Project once achieved through raw discovery.

The implications are sobering: the very institutions designed to preserve America’s technological edge are being used as unwitting conduits in a modern-era science war. Each breach, partnership, or personnel compromise erodes not only the security of critical innovations but also the trust upon which America’s open research ecosystem depends.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has leveraged the Thousand Talents Program (TTP) to steal intellectual property (IP) and advance its strategic objectives. The TTP was launched in 2008, shortly after the CCP announced its goal to become an “innovative country” by 2020 and the world’s leader in science and technology (S&T) by 2050. Since the program’s inception, it has recruited thousands of scientists from across the globe, including in the U.S.A.

The University Connection

If the national laboratories are the fortresses of American science, the universities of the Southwest are their outer walls — open, collaborative, and increasingly vulnerable. Chinese talent programs and research exchange networks have learned that it is far easier to penetrate the periphery than to storm the gate. Universities like Arizona State, University of Arizona, and the University of New Mexico occupy a strategic position at the intersection of open research, defense contracting, and commercial technology transfer.

A 2022 Department of Education disclosure review revealed that Arizona State University had received over $14 million in previously unreported foreign funding, including from Chinese state-affiliated institutions linked to artificial intelligence and materials research. The University of Arizona, through its optical sciences and aerospace engineering programs, has also been identified by counterintelligence analysts as a secondary target in Chinese “nontraditional collector” efforts — leveraging graduate researchers, visiting scholars, and commercial partnerships to obtain defense-adjacent innovations in imaging, satellite calibration, and navigation.

Meanwhile, the University of New Mexico’s proximity to Sandia and Los Alamos National Laboratories has made it a persistent focus of MSS-linked recruitment operations. A 2021 FBI briefing to regional academic security officers cited multiple cases where visiting researchers or postdoctoral candidates sought unauthorized access to lab-linked supercomputing clusters and experimental data servers.

This strategy — exploit the open exchange of science under the guise of collaboration — allows Chinese entities to legally harvest sensitive data with minimal risk of exposure. Beijing’s Thousand Talents Program, now officially disbanded but reconstituted under newer frameworks such as the “Overseas Expertise Introduction Program,” continues to offer financial incentives to scientists who transfer research back to Chinese universities or defense-linked enterprises. The result is a shadow pipeline of intellectual property flowing eastward, much of it unclassified but cumulatively transformative.

For policymakers and intelligence professionals, the warning is clear: the battleground is no longer limited to top-secret facilities or encrypted servers. It extends into classrooms, laboratories, and grant-funded partnerships where innovation and espionage now share the same zip code. The openness that built American technological leadership — collaboration, publication, and peer exchange — is being systematically weaponized against it.

“The greatest long-term threat to our nation’s information and intellectual property … is the counterintelligence and economic espionage threat from China.”

FBI Director Christopher Wray

Speech at the Hudson Institute

Sandia National Laboratories

In 2014 a former Sandia scientist (Jianyu Huang) pleaded guilty after taking Sandia government-owned equipment to China and making false statements; the case was prosecuted by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in New Mexico. Department of Justice

Los Alamos National Laboratory

A senior scientist (Turab Lookman) pled guilty and was sentenced (probation/fine) after lying to counterintelligence about his recruitment into China’s “Thousand Talents” talent-recruitment program — a high-profile indicator of PRC talent-recruitment work inside an NNSA lab. Department of Justice+1

Historic LANL Espionage Scandal

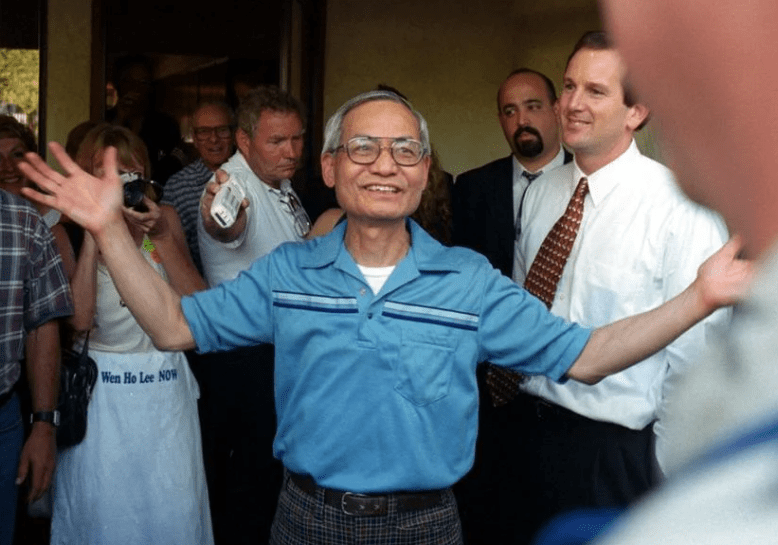

The Wen Ho Lee investigation (1999) remains a foundational case illustrating the national-security consequences and political sensitivity of suspected transfers from Los Alamos — an important historical precedent for modern recruitment and exfiltration concerns in New Mexico. Wikipedia

San Francisco Bay-Area Engineer

In 2024–2025 DOJ unsealed charges and later a guilty plea against a Bay-Area engineer (Chenguang Gong) accused of taking thousands of files relating to infrared sensors, missile-detection and other defense systems — a direct trade-secret theft case tied to Chinese talent-recruitment.

PRC Cyber Campaigns

U.S. agencies (NSA / FBI / CISA) and industry reported that PRC-linked actors known as “Volt Typhoon” had compromised IT/OT environments across multiple U.S. critical-infrastructure sectors (energy, water, communications) capable of affecting utilities in any state, including the Southwest. CISA+1

Foreign Land Holdings in Nevada

USDA AFIDA reporting show Nevada is among states with notable percentages of foreign-held agricultural acreage; those datasets are the evidentiary basis for national-security scrutiny of foreign landownership near sensitive facilities and infrastructure in the West. Farm Service Agency+1

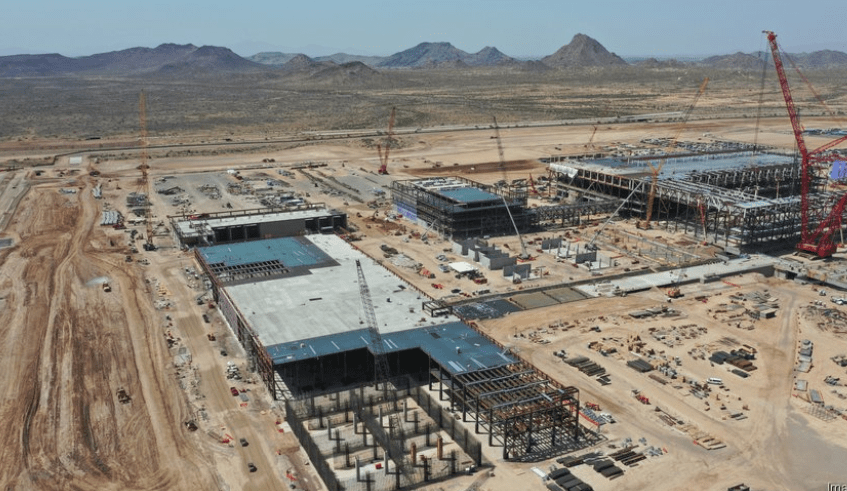

The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is building a total of six fabrication plants on its campus in north Phoenix, Arizona pictured above during construction. The first fab is already operational and producing advanced 4-nanometer (nm) chips.

The next fabs will produce even more advanced chips, including 3 nm, 2 nm, and 1.6 nm technology. The project represents one of the largest foreign investments in U.S. history, with a total pledged investment of $165 billion as of March 2025.

The project is supported by the U.S. CHIPS and Science Act, which has awarded TSMC Arizona up to $6.6 billion in direct funding and up to $5 billion in loans.

Industrial Espionage and Infrastructure

Espionage in the Southwest does not always look like cloak-and-dagger intrigue. It often looks like a joint venture, a supplier contract, or a foreign investment filing. The People’s Republic of China has learned that America’s high desert is not just home to missile ranges and physics labs — it is also the logistical heart of the nation’s defense industrial base. From semiconductor fabrication to lithium extraction, the region’s infrastructure has become a latticework of opportunity for covert access, influence, and technology acquisition.

In Arizona, the semiconductor boom catalyzed by the CHIPS and Science Act has drawn both allies and adversaries. As Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) builds its new megafab in Phoenix, Chinese industrial intelligence networks have reportedly intensified targeting of subcontractors and materials suppliers. A 2023 FBI and CISA joint advisory warned that “foreign state actors are seeking to infiltrate or compromise vendors with indirect access to critical chip manufacturing processes.” Investigations tied to Chinese-linked intermediaries in the cleanroom filtration, wafer etching, and logistics sectors have underscored the vulnerability of the supply chain below the Tier 1 contractor level — the layer where federal security protocols thin out.

Caption: Nevada’s emerging role in battery materials and drone manufacturing has created new exposure points. The state’s lithium fields in Thacker Pass and its sprawling industrial corridor around Reno-Sparks have attracted intense foreign commercial interest, including attempted joint ventures by firms with opaque Chinese capital structures.

In one 2024 case, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) quietly blocked a proposed equity purchase in a Nevada-based battery recycling startup after intelligence analysis linked the buyer to China Minmetals Corporation, a state-owned enterprise under Beijing’s State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC).

Infrastructure, too, is in play. Chinese-made components remain embedded in America’s power grid and telecommunication backbones. Utility-scale solar farms, many using inverters or monitoring systems sourced from PRC-affiliated manufacturers, present latent cybersecurity risks. DHS has warned that such hardware could allow for remote command insertion or data exfiltration. When combined with Beijing’s demonstrated capabilities in industrial cyber reconnaissance — probing networked systems to map vulnerabilities without triggering alarms — these footholds become dual-use assets: energy producers by day, potential espionage conduits by night.

Taken together, these vectors form the economic face of infiltration. The MSS no longer needs to rely solely on spies or hackers; it can leverage corporate law, private equity, and global supply chains to build advanced weapons and achieve strategic depth.

Top Six Takeaways

The Southwest is America’s new security frontier — where national laboratories, semiconductor fabs, and energy grids intersect in the “science war of the century”.

China’s MSS has shifted from theft to integration, embedding within legitimate partnerships and corporate structures to achieve enduring access.

Universities are the connective tissue — providing open portals between basic science, defense applications, and foreign influence.

Critical infrastructure and supply chains remain the soft underbelly, particularly in sectors like semiconductors, lithium extraction, and renewable energy systems.

Counterintelligence must become proactive and predictive, fusing intelligence, law enforcement, and academia to map adversarial behavior before breaches occur.

The contest is cultural as much as technological — safeguarding innovation now requires vigilance, transparency, and a new national awareness of how influence operates . . . in plain sight.

Conclusion: Dragons in the Desert

The infiltration of the American Southwest is not cinematic — no spy swaps, no satellite shootdowns. It is quieter, procedural, and cumulative. It unfolds in research partnerships, venture capital term sheets, and firmware updates pushed over the air to the devices in our work places and homes. Taken together, these threads form a strategic encirclement of the nation’s innovation core — a long game designed to hollow out American advantage from the inside out.

The laboratories and defense installations scattered across New Mexico, Nevada, and Arizona represent the frontier of U.S. technological sovereignty. What’s at stake is not just intellectual property but the continuity of deterrence itself — the ability to innovate faster, deploy smarter, and protect the scientific foundations that underpin military and economic power.

Beijing’s intelligence doctrine has adapted accordingly: less about theft in the traditional sense, more about co-location — embedding within America’s innovation ecosystems until visibility and unfettered access provides the upper hand and battlefield technological advantage.

In the desert, data crosses every border; code travels at the speed of light and the same networks that connect labs, suppliers, and universities now double as attack surfaces.

America’s deserts once forged the atomic age — now they will determine who commands the next one.

Additional Information

CHINA

IN

NEW

ENGLAND

Sources, Acknowledgements and Image Credits

{1} China in New Mexico | Inside Beijing’s Science War for the American South West. An Expert Network report by PWK International Managing Director David E. Tashji October 27, 2025. (C) 2025 PWK International

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, or academic work, or as otherwise permitted by applicable copyright law.

“China in New Mexico” and all associated content, including but not limited to the report title, cover design, internal design, maps, engineering drawings, infographics and chapter structure are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use, adaptation, translation, or distribution of this work, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.

This report is a work of non-fiction based on publicly available information, expert interviews, and independent analysis. While every effort has been made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any employer, client, or affiliated organization.

All company names, product names, and trademarks mentioned in this report are the property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. No endorsement by, or affiliation with, any third party is implied.

{2} China in New Mexico | Inside Beijing’s Science War for the American South West. Image Credit: PWK International October 26, 2025.

{3} The American Southwest has always been a proving ground, Infographic source and credit: PWK International. October 17, 2025.

{4} “New Mexico – Where America Tests Tomorrow” Infographic source and credit: PWK International. October 14, 2025.

{5} DOJ: Former Sandia scientist plea/conviction press release. Department of Justice

{6} DOJ / USAO (New Mexico): Los Alamos (Turab Lookman) indictment/plea and sentencing material. Department of Justice+1

{7} Background: Wen Ho Lee (Los Alamos case, historic). Wikipedia

{8} DOJ (Central District of California): Yi-Chi Shih case (illegal export of MMICs). Department of Justice

{9} DOJ / Central District of California: Chenguang Gong complaint/press reporting on trade-secret theft. Department of Justice+1

{10} DOJ: Xuehua “Edward” Peng illegal-agent prosecution (Northern California). Wikipedia

{11} CISA / Joint advisory: Volt Typhoon — PRC state-sponsored compromise of critical infrastructure. CISA+1

{12} Mandiant / Google TAG / FBI: APT41 and similar PRC APT activity affecting U.S. organizations. Google Cloud+1

{13} USDA / AFIDA & GAO: Foreign holdings of U.S. agricultural land (AFIDA 2023 report; GAO review of foreign land and national-security risk). Farm Service Agency+1

{14} Treasury / White House / Reuters: CFIUS/Treasury actions and forced divestiture precedent for PRC-linked property near sensitive sites. Reuters+1

{15} Insider risk + talent programs: DOJ prosecutions in New Mexico and California (items 1–6) show a persistent pattern: the PRC’s talent-recruitment ecosystem and individual compromise or false-statement cases frequently touch the national-lab and university communities that anchor the Southwest. Department of Justice+2Department of Justice+2

{16} Cyber pre-positioning: CISA/Microsoft advisories about Volt Typhoon and other PRC actors describe “living-off-the-land” techniques and sustained access inside IT/OT networks. That means utilities, water systems and industrial control systems across the Southwest are part of the same risk surface that has already been abused elsewhere. CISA

{17} Economic and real-estate vectors: AFIDA and CFIUS activity show the PRC’s toolkit is broader than spies and hackers — it includes land, investment, data-center and supply-chain positioning that can be leveraged strategically if access is consolidated. Farm Service Agency+1

{18} Wen Ho Lee Case & Nuclear Espionage — A definitive overview of China’s effort to acquire U.S. nuclear weapons data, especially at labs like Los Alamos and Sandia. EveryCRSReport+2Intelligence Resource Program+2

{19} Chinese Microchip Export Case (Aug 5, 2025) — “Two Chinese nationals arrested for illegally exporting tens of millions of dollars of sensitive microchips to China via trans-shipment routes.” Department of Justice+2Department of Justice+2

{20} Cadence Design Systems Agrees to Plead Guilty and Pay Over $140 Million for Unlawfully Exporting Semiconductor Design Tools to a Restricted PRC Military University.

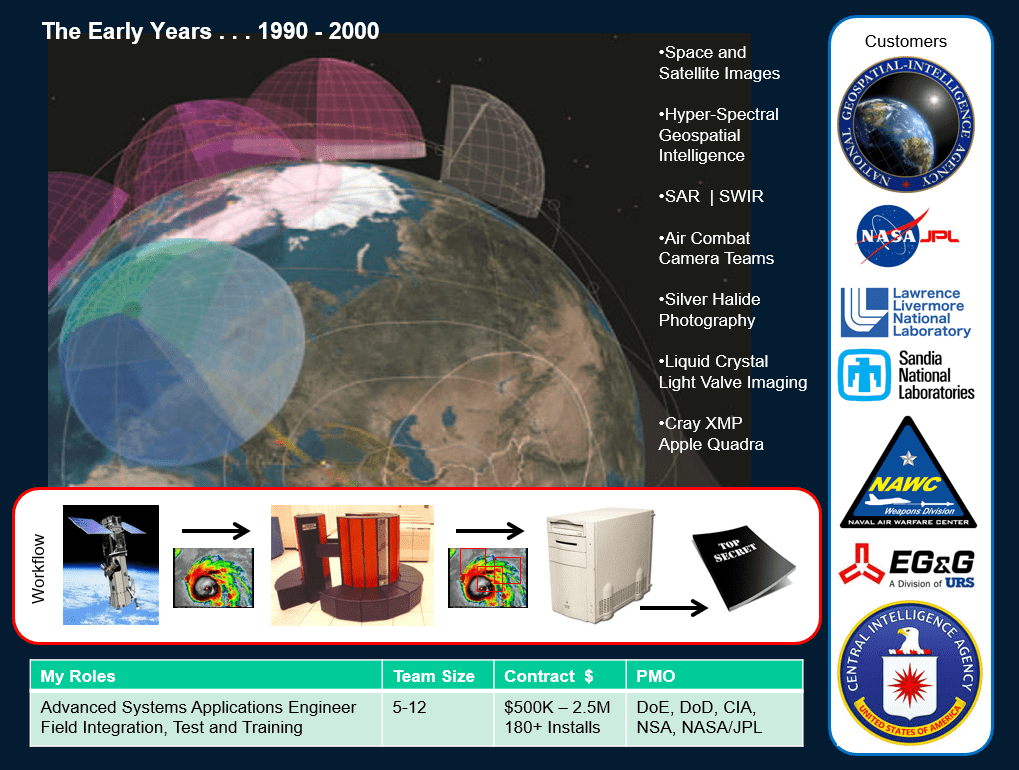

AUTHORS NOTE: Some of the insights in this report are informed from my own first-hand experience working within America’s advanced technology ecosystem in New Mexico, Nevada, California, and elsewhere across the desert south west. My work as an applications engineer involved supporting U.S. government programs at Sandia, Los Alamos, Livermore, EG&G, Jet Propulsion Laboratories and many others — helping operationalize and interface computer systems with super computers like the CRAY X-MP, offering big data analytics for government leader decision advantage.

My time inside the Department of Energy and Department of War science and research ecosystem has been invaluable, and informs our investigative research into how south west science innovation powers Americas future in an era of asymmetric and algorithmically boosted Great Power Competition.

About PWK International

PWK International provides strategic intelligence and national security consulting to clients operating at the intersection of technology, defense, and global finance. From government agencies and aerospace primes to hedge funds and innovation startups, we help organizations interpret geopolitical risk through the lens of technology and acquisition.

Our work is grounded in field-informed analysis — tracing the flow of capital, data, and influence across emerging technologies and contested regions and domains. Through in-depth research and proprietary reporting, PWK International has become a trusted source for understanding how foreign intelligence services, industrial competitors, and state-linked investors shape the business of American power.

For clients navigating complex procurement cycles, innovation pipelines, or cross-border investment portfolios, we provide insight that bridges strategy and execution. Whether assessing risk in the defense supply chain or forecasting global trends in dual-use technology, PWK International equips leaders with the right data driven intelligence in a fast moving world filled with volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA).

Pingback: China in Silicon Valley |

Pingback: Billionaires at War: High Stakes and High Net Worth |