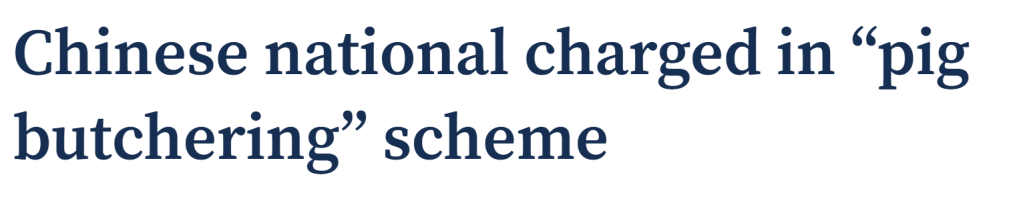

China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) is no longer an ocean away. From Palo Alto to Mountain View to Los Gatos and beyond, the MSS has quietly embedded itself in the pitch decks, research labs, venture portfolios, and cloud services platforms that define America’s technological edge.

The world’s largest and most secretive intel agency has prosecuted their asymmetric, intel first 100 year technology strategy with a quiet, persistent presence that blends state controlled capital investments in US technology companies, land and resource acquisitions near sensitive military sites, intellectual property theft from US universities and national laboratories, social engineering and academic talent recruiting with invisible cash payments, electric and water supply infrastructure cyber intrusions, dirty handed influence campaigns, phony front companies, illegal and unregistered marijuana grow farms, cocaine and fentanyl trafficking rings funding covert operations, cryptocurrency and casino money laundering schemes . . . and worse. It’s a sophisticated, multi-domain approach to strategic infiltration and a long game designed to shape, steer, and siphon the breakthroughs that will determine the balance of power in this century.

This report will map how Beijing’s Ministry of State Security and its network of state-backed investors, talent recruiters, proxies and technology brokers operate within the Valley’s open innovation culture. This report unpacks the full toolkit of influence: land ownership by CCP-linked entities, state-backed venture capital, intellectual property theft disguised as partnerships, talent poaching through university pipelines and startup hiring, narcotics-trafficking and money-laundering networks that finance covert operations, and intelligence collection that targets everything from semiconductor IP and AI models to biodefense research and supply-chain algorithms. Together, these seemingly disconnected vectors form a highly sophisticated multi-domain approach to infiltration . . . one designed to harvest American ingenuity at its source.

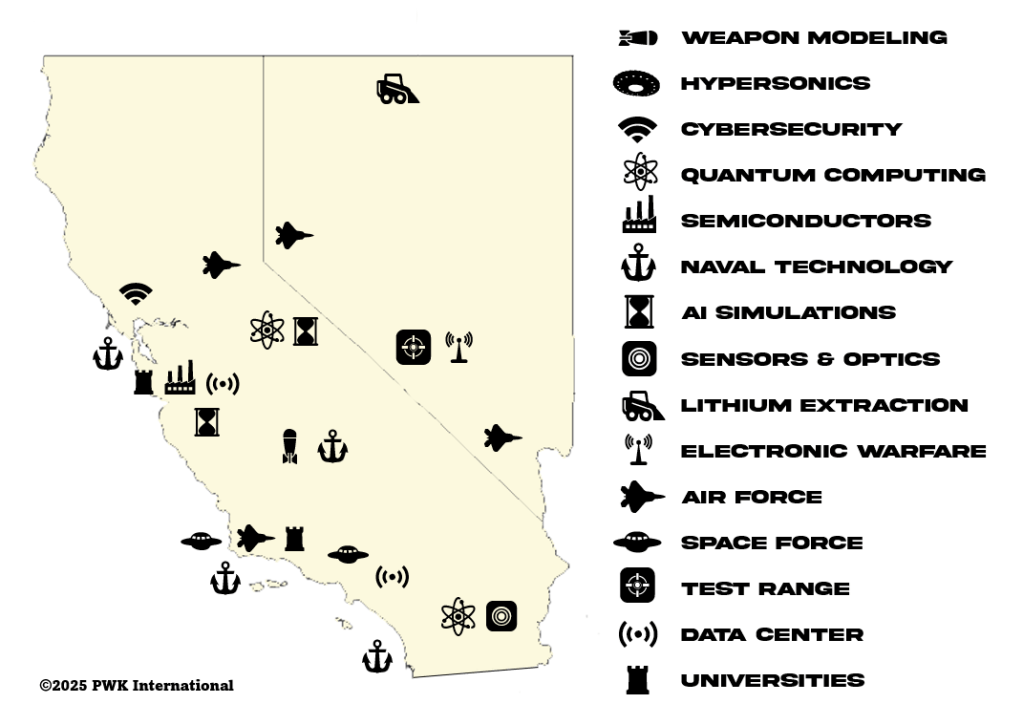

AMERICAS INNOVATION CORRIDOR | CALIFORNIA AND NEVADA

This map illustrates the dense and overlapping ecosystem of advanced technology, national defense infrastructure, and research powerhouses that define California and Nevada . . . an environment that offers extraordinary opportunity for innovation and extraordinary vulnerability to foreign exploitation. From quantum computing labs at National Laboratories to naval technology centers along the coast, from lithium fields in Nevada to Air Force and Space Force installations across the interior, the region forms one of the most strategically valuable innovation corridors in the world.

Together, these nodes tell a single story: Silicon Valley and its surrounding science corridors are not just economic engines—they are active battlegrounds in great power competition, where every data center, university, hypersonics lab, semiconductor facility, and test range represents both a national asset and a potential target.

This report offers an assessment of how China has weaponized the Valley’s strengths—its openness, speed, and trust-driven deal culture—to build asymmetric advantages in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, aerospace autonomy, biotech, and cyber offense. It illustrates how soft-power investment masquerades as collaboration, how “friendly” limited partners act as data-collection conduits, and how joint research programs and accelerators create gray-zone environments where sensitive breakthroughs quietly migrate overseas. The objective is not only to acquire technology, but to shape the architectures of the future: the AI models, chips, data reservoirs, and dual-use platforms that will underpin both global markets and military power.

For founders, investors, policymakers, and national-security leaders, the stakes are clear. Silicon Valley is no longer just building the future—it is now the battlefield where the future is being contested. This report aims to give readers a comprehensive framework for understanding how the CCP’s long-game strategy intersects with America’s most important engine of innovation. It details the risks, reveals the patterns, and lays out the implications for economic security, defense resilience, and the sovereignty of American technological leadership.

Why Silicon Valley?

Silicon Valley is an ecosystem finely tuned to convert ideas into capital, code, and deployment at scale. For an adversary looking to accelerate technology, harvest intellectual property, or quietly shift the architecture of global power, nothing beats the Valley’s metabolic rate. It concentrates what military planners and industrial spies both prize most: dense talent, vast pools of venture capital, permissive corporate cultures that prize speed over scrutiny, and an open research pipeline that feeds everything from semiconductor designs to machine-learning models.

First, the Valley’s human capital is unparalleled. Universities, postdocs, industry labs, and startups form a single labor market in which PhDs, engineers, and product managers flow freely from academia to commerce to government contracts. That mobility is the engine of innovation, but it is also a natural recruitment ground for foreign talent programs and state-linked talent brokers. An outside actor need not steal a factory or buy a shipyard; it can simply hire, lure, fund, or co-opt an engineer who already understands the codebase, the supply chain, and the product roadmap. The Thousand Talents model — and its many successors and mimics — doesn’t always need explicit illicit inducements. Sometimes a fellowship, a consultant contract, or a whispered promise of a lab directorship abroad is all it takes to convert knowledge at scale into a strategic advantage.

17,250 Students

2,345 Faculty Members

8,180 Acre Campus

7,500 Research Projects

$2.2 Billion Budget

20 Nobel Laureates

Silicon Valley’s financial plumbing is a vector in its own right. Venture capital is a high-velocity money pump that amplifies risk and masks origin stories. State-linked funds, sovereign wealth vehicles, and politically connected limited partners can use opaque structures to seed startups at the earliest, most formative stages. Early investment buys board seats, data access, and privileged product insights long before a technology reaches maturity. The startup world’s fetish for “smart capital” — investors who claim to bring more than money, who carry clients, supply-chain connections, or market access — becomes a Trojan horse when those investors answer to foreign states. Even innocuous accelerator programs or joint R&D funds can become collection points: repositories of datasets, training corpora, and experimental architectures that, once exported or mirrored, give an adversary a head start measured in years.

The Valley’s materials and supply chains are globally entangled and extremely fragile — which makes them excellent levers for asymmetric pressure. Microelectronics, chips, photonics, and specialized sensors rely on layers of subcontractors and suppliers scattered across countries and legal regimes. A targeted investment or acquisition at a single supplier halfway down the stack can produce outsized leverage: slow the fab line, poison the test yields, or insert a firmware update that creates a latent capability. Unlike conventional military hardware, these digital and material choke points are small, often invisible, and politically deniable. They are the perfect instruments for an adversary that wants to “shape” outcomes without triggering kinetic escalation.

Donald Trump’s return to the presidency is reshaping Silicon Valley’s regulatory environment. His pro-deregulation stance is welcomed by some entrepreneurs, who see it as a way to accelerate innovation with fewer constraints.

Caption: President Donald Trump with journalists, Elon Musk, and X Æ A-Xii in the Oval Office, February 11, 2025.

Data is the new raw material, and Silicon Valley sits on an unimaginable volume of it. Startups and cloud providers collect telemetry on human behavior, industrial processes, geospatial flows, and biological assays. That data — raw, curated, or labeled — is the feedstock for modern machine learning. Whoever controls the best datasets and the cleanest training pipelines will dominate AI outcomes: perception systems, predictive logistics, autonomous control, and biotech discovery. The subtle theft of a dataset, the copying of an architecture, or the seeding of biased training inputs can change the contours of future capabilities. Worse, these acts are hard to detect and even harder to attribute publicly; the damage is structural and accrues over time.

Silicon Valley’s business culture amplifies all of the above. The region celebrates openness, sharing, and permissive licensing; it rewards speed over caution. Startups rush to integrate third-party libraries, outsource non-core functions, and roll out features with minimal gating. That product-first ethos creates a background hum of technical debt and dependency. Each dependency is a potential backdoor, each outsourced test bench is a potential supply-chain leak, each cloud integration is an potential exfiltration path. For an intelligence service accustomed to patient, layered operations, the Valley is an embarrassment of riches: too many entry points, too many trusted relationships, and a governance model that mistrusts bureaucratic constraint.

Finally, the Valley’s prestige and social architecture provide the perfect cover. Conferences, accelerator demo days, invited talks, and visiting researcher programs are public rituals of legitimacy. They allow state-linked actors to operate under the veneer of normal collaboration. Seed-stage deals are table stakes for influence; guest lectures are recruiting events in disguise; partnerships and joint ventures create plausible deniability for activities that, if disclosed, would be politically awkward. Add to that the money-laundering and regulatory arbitrage techniques that can reroute capital through benign jurisdictions, and the result is a system where strategic intent can be hidden in plain sight.

All of these features — talent density, financial opacity, fragile supply chains, troves of training data, permissive engineering cultures, and a social calendar of legitimating rituals — make Silicon Valley uniquely dangerous as a target. An adversary that masters these vectors does not need to match the United States in firepower; it only needs to insert itself into the flows that produce advantage. That insertion is precisely what the CCP has been quietly cultivating: a long-term strategy of influence, access, and selective exfiltration that turns collaboration into strategic exploitation.

Use the DOJ links to read the details of each arrest. Real cases, prosecutions, forced divestitures, whistleblower reports, cyber-forensics and influence operations — this report illuminates exactly how the MSS multi-domain strategy manifests on the ground.

Linwei “Leon” Ding (Newark, CA) – Theft of AI trade secrets from Google

A former Google software engineer was indicted March 6 2024 for uploading more than 500 confidential files related to Google’s AI/TPU hardware to his personal account while secretly working with China-based companies. He’s also charged in a February 2025 superseding indictment with seven counts of economic espionage and seven of trade secret theft. DOJ

Chenguang Gong (San Jose, CA) – guilty of stealing missile-detection tech for China

On July 21 2025 the DOJ announced Gong pleaded guilty to one count of theft of trade secrets after transferring more than 3,600 files from a U.S. defense contractor containing blueprints for infrared sensors and hypersonic-missile detection systems. DOJ

Xuehua Peng (Hayward, CA) – Illegal agent of the People’s Republic of China

A Northern California resident was charged in September 2019 with acting as an illegal agent of the PRC: using dead-drops, surreptitious meetings and intelligence collection inside the Bay Area. DOJ

Linwei Ding (Bay Area CA)

Ex Google engineer convicted of

stealing artificial intelligence trade secrets to benefit two Chinese companies he was secretly working for. REUTERS

Two Chinese nationals arrested for laundering at least $73 million via shell companies tied to crypto scams (Temple City / Los Angeles, CA)

On May 17 2024 prosecutors unsealed an indictment charging Yicheng Zhang, a Chinese national resident of Temple City, CA, and Daren Li (dual citizen China/St. Kitts & Nevis) with laundering at least $73 million through shell companies from U.S. crypto scams. DOJ

Qiunan Li sentenced for laundering ~$3.5 million from investment scams (Los Angeles, CA)

Li Liu (a.k.a. Qiunan Li / Xiaoying Zhao), age 27, was sentenced on Aug 14 2025 to 28 months in federal prison for laundering approximately $3.5 million stolen from U.S. victims via investment-fraud schemes. DOJ

Fei Liao (San Gabriel, CA)

A Chinese national from San Gabriel, CA, Fei Liao, was charged with conspiracy to commit wire fraud and money laundering in a crypto investment scam that used “pig-butchering” methods to defraud U.S. victims. DOJ

The CCP’s Playbook in America’s Innovation Core

If Silicon Valley is the greatest concentration of future-shaping power on the planet, China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS), the United Front Work Department (UFWD), and state-aligned investment vehicles have spent two decades developing a playbook to quietly plug themselves into its bloodstream. The Chinese Communist Party does not need to conquer the Valley; it only needs to participate in it — strategically, selectively, and with plausible deniability.

Venture Capital as Vector: The Capital Camouflage Strategy

Silicon Valley was built on a simple assumption: money behaves like money. Investors look for returns. They want exits. They want upside. But the CCP plays a different game—one where state-backed funds like China Investment Corporation, SAIC Capital, ZGC Capital, and nominally “private” entities like Tencent, Alibaba, and Baidu Ventures allocate capital with dual mandates:

- Acquire emerging technologies that advance Beijing’s national strategy.

- Develop dependency relationships that turn innovators into quiet partners.

This is not paranoia. It is documented in China’s own industrial doctrines: Made in China 2025, the National Intelligence Law, the Military-Civil Fusion Strategy, and the CCP’s “go out” policy for overseas investment. Every yuan deployed abroad may be private in paperwork, but it is political in purpose.

Money moves faster than regulation. The CCP understands that influence follows capital, and that early-stage investment is the cheapest way to shape a startup’s destiny. Through layered funds, offshore partnerships, Hong Kong intermediaries, and ostensibly private Chinese venture firms, Beijing’s financial apparatus inserts itself into pre-Series A financing rounds where:

- Board seats are easier to obtain

- Product direction is more malleable

- Founders are most vulnerable to capital scarcity

Early investment yields visibility into codebases, client relationships, technical milestones, and — most importantly — the internal telemetry of emerging AI systems. Even a small LP stake in a U.S. fund can create “information rights lite,” granting updates, pitch decks, quarterly assessments, and sometimes access to limited technical detail. By the time a startup becomes aware of the strategic implications, it may already be entangled in a board structure or cap table that creates national-security headaches.

The brilliance of this method is its deniability: the checks are small, the structures are clean, the vehicles look like any other growth-hungry investor. Yet the strategic yield is enormous.

Talent Pipelines: Recruitment Disguised as Opportunity

People — not hardware — carry the most valuable secrets. China’s global talent programs, both formal and informal, approach Silicon Valley through soft power, not coercion: visiting professorships, cross-border accelerator programs, collaborative fellowships, and offers of funding for labs in Shenzhen or Beijing. These arrangements often look benign:

- Joint R&D centers

- Scholarly exchange agreements

- Dual-appointment affiliations

- Startup incubators linked to municipal governments

Once talent is in the pipeline, the extraction becomes subtle. Researchers are asked for datasets, algorithms, unpublished designs, prototype results, or simply “feedback” on a state-backed lab’s internal work. Nothing dramatic — no cloak-and-dagger — just the incremental siphoning of tacit knowledge that cost U.S. taxpayers billions to create.

Talent Wars: Poaching the Minds Behind the Machines

Silicon Valley doesn’t run on silicon. It runs on people—scientists, engineers, founders, researchers, and the unquantifiable human spark that produces the next breakthrough. And Beijing knows that if you want the technology of tomorrow, the cleanest path is simple:

Take the people who know how to build it.

While the headlines focus on spies, data breaches, and investment flows, the real battleground is talent—who has it, who keeps it, and who controls the environments where innovation happens. It is here, in the quiet corridors of academia, research labs, and startup offices, that the CCP’s softest touch becomes its sharpest tool.

Corporate Talent Drains

Inside U.S. companies, the tactics evolve:

- Poaching engineers with above-market compensation packages paid through Chinese subsidiaries.

- Contractor networks that create legal distance while enabling sensitive access.

- Dual-employment arrangements where researchers work for a U.S. firm and a Chinese university simultaneously.

- Temporary assignment pipelines that allow short-term rotational placements in labs connected to the PLA or state-owned enterprises.

- Manufacturing dependencies that force U.S. startups to interface with Chinese partners and reveal operational details.

Every technique is subtle. Every access point seems benign. But when multiplied across hundreds of companies, the impact is profound: a gradual drift of the Valley’s intellectual capital into Beijing’s strategic orbit.

IP Acquisition: From Cyber Theft to Corporate Courtship

Beijing’s approach to intellectual property theft in the tech sector spans the entire spectrum of intrusion:

- Covert cyber penetration of cloud environments

- Supply-chain compromises through dev tools or firmware

- Corporate partnerships that quietly require tech transfer

- M&A attempts structured to acquire key patents or staff

- Shell companies used to obtain prototypes or restricted components

The Valley’s speed culture — ship fast, fix later — means internal security programs often lag. Startups running on thin margins do not prioritize segmentation, encryption, logging, or insider-threat programs. A sophisticated adversary does not need to breach Google or NVIDIA if it can infiltrate a six-person subcontractor whose cloud bucket contains the same source materials.

China’s strategy does not rely on a single spectacular breach. It relies on accumulation: 100 small wins that add up to an enormous leap.

Narcotics, Laundering, and Shadow Capital Flows

This is the darkest and least understood element of the playbook — the financial gray zone. U.S. law enforcement has repeatedly traced fentanyl precursor distribution networks, cryptocurrency laundering channels, and underground banking systems back to PRC-linked networks. While these operations target crime, not espionage, the financial infrastructure overlaps:

- Laundering networks move capital internationally without scrutiny

- Chemical suppliers operate in zones of weak enforcement

- Criminal intermediaries can serve as cutouts for sensitive transactions

- Shell entities can funnel money into investments or influence campaigns

If venture capital is Beijing’s soft power instrument, illicit finance is its shadow power instrument. Both create conduits that bypass conventional compliance systems — an advantage that is uniquely useful in a region like Silicon Valley where capital flows define the ecosystem.

Social Engineering and Influence: The Human Access Vector

Beyond code and capital, the CCP invests heavily in relationships — the long game of grooming founders, researchers, professors, postdocs, community organizers, and diaspora leaders. Through UFWD-linked associations, cultural groups, talent dinners, and professional networking events, influence operations create:

- Gatekeepers who can introduce investors

- Community figures who can shape local narratives

- Researchers who normalize “friendly collaboration”

- Student groups that shape campus discourse

- Advisors who steer founders toward PRC-linked opportunities

The aim is not always espionage. More often, it is to normalize economic dependence, social reciprocity, and a narrative framework in which U.S.–China technology collaboration is “inevitable” and security concerns are “political noise.” Influence operations soften the environment so intelligence operations encounter less friction.

Real Estate and Land Acquisition: The Physical Footprint

Although less dramatic than in agricultural regions or near military bases, Silicon Valley has seen foreign entities — including PRC-linked investors — acquire:

- Office parks

- Data-center parcels

- Properties adjacent to telecom infrastructure

- Warehouses suitable for covert logistics

- Multi-use facilities that can house startups or “innovation centers”

Real estate is strategic for one simple reason: control the ground, control the flow. A building can host a startup accelerator, a shell VC, a cultural organization, or a front company — all under one roof. And in a region where space is scarce and expensive, a single property can influence the technical networks running through it.

China’s approach is modular, layered, and adaptive — not a single strategy but a portfolio of overlapping tactics calibrated for Silicon Valley’s vulnerabilities. It is not espionage in the Hollywood sense; it is strategic participation engineered to tilt the future.

Innovation at the Threshold of Compromise

For Silicon Valley, the tragedy is that many founders still assume they are too small, too early, or too obscure to be targets. Yet the CCP doesn’t care about valuation—it cares about future potential. A startup with five employees and a prototype can be more valuable than a Fortune 500 giant if the underlying technology aligns with:

- AI autonomy

- Quantum materials

- Bioengineering

- Cryptography

- Hypersonics

- Next-gen semiconductors

- Synthetic data

- Aerospace composites

The smaller the company, the easier the compromise.

Talent drains don’t just transfer knowledge. They redirect the trajectory of innovation. Each poached engineer, each dual-affiliated researcher, each quietly recruited postdoc shifts a sliver of America’s technological edge across the Pacific.

And when multiplied over a decade, those slivers become a strategic advantage.

The Art of Accretion

Espionage used to be an event—a break-in, a secret meeting, a sudden revelation. Now it is often a process: accrete, normalize, and extract. A Chinese-linked investor takes a small equity stake. A researcher accepts a modest fellowship. A contractor signs a supply agreement. Each step is ordinary. Taken together, they form a pipeline for intellectual transfer.

This patience is not accidental; it is a strategic posture. Accretion avoids headlines and attribution. It converts countless unremarkable acts into a single strategic outcome: the transfer of design patterns, training data, prototype validation methods, and tacit engineering knowledge. For an intelligence service, this kind of slow build is more valuable—and more survivable—than a single spectacular heist.

Digital Laundry: When Data Goes Missing and Reappears Clean

Data laundering is the modern equivalent of smuggling: make something illicit appear legitimate. In the Valley, this often looks like perfectly legal activity—a cloud export, a joint dataset exchange, a “sanitized” copy of a training corpus shared under an NDA. The trick is the path:

- A dataset is built in California, labeled and curated for a startup’s model training.

- The dataset is replicated to clouds that sit in third-party vendor accounts.

- Copies are accessed through contractor accounts or third-party service providers with lax controls.

- The same data re-appears inside a university lab in Shenzhen or a state-linked AI institute—legally difficult to prove, operationally devastating.

Because the movement flows through legitimate commercial services, it is hard to litigate and harder to stop. By the time an investigator traces the flow, the strategic advantage has been baked into a rival’s model or product roadmap.

Supply-Chain Intrusion: Tiny Components, Huge Leverage

Not all theft is digital. Sometimes the exploit is physical and mundane: a firmware update, an altered test jig, a replaced component in a sensor array. The supply chain beneath AI and hardware startups is a forest of small vendors: contract manufacturers, test labs, sensor houses, and firmware integrators. Each constitutes a potential attack surface.

An adversary that controls or influences a Tier-2 supplier can:

- Insert a latent capability into a device’s firmware.

- Introduce a reproducible fault that leaks operational data.

- Cause intermittent failures that force rushed patches and exposures.

- Access telemetry data from client devices worldwide.

The business logic of outsourcing—speed, cost, flexibility—creates vulnerability. Manipulating the supply chain is not dramatic; it is surgical and corrosive.

Legal Grayness and Financial Camouflage

Beijing’s playbook also exploits legal and financial seams. Complex ownership structures—layered shell companies, Cayman-registered funds, Hong Kong intermediaries—mask the true origin of capital. Transactions run through benign jurisdictions and legitimate vehicles, creating audit trails that look clean and defensible. Similarly, joint ventures and licensing deals can be written to comply with letter-of-law requirements while routing know-how through subsidiaries that operate under different standards.

This legal grayness matters because national security frameworks are built on clarity: clear attribution, clear intent, clear ownership. When an ill intent is wrapped in corporate form, traditional tools—sanctions, prosecution, public exposure—lose potency.

Case Notes — How the Playbook Manifests

Across recent years, multiple public cases have illustrated the gray-zone playbook in action: investment rounds that led to forced divestitures, DOJ indictments for IP theft, CFIUS interventions halting acquisitions, and public revelations about joint labs that funneled data overseas. Each case is different in detail, but similar in logic: access gained through ordinary commercial relationships, strategic advantage gained through ordinary commercial outputs.

The lesson is clear: modern industrial espionage is less a break-in and more a process of legalized capture. It is harder to see, harder to stop, and easier to normalize than classic Cold War spy craft.

1, Silicon Valley is now a strategic battlespace in the “Science War of the Century”. China targets the Valley because it produces the worlds leading ontologies and architectures—AI, cyber, quantum, autonomy—that define modern power, influence, and deterrence.

2. Investment is Beijing’s Trojan horse. State-linked capital, layered ownership schemas, opaque financing structures, and “benign” venture funds create access to IP, data, and talent that traditional espionage could never reach. The business of spying has changed in unsettling new ways.

3. Talent pipelines are the soft center of U.S. innovation. The CCP leverages academic programs, research fellowships, invisible cash payments and industry mobility to quietly acquire skills, research breakthroughs, and tacit engineering knowledge. The Thousand Talents program may have a new name, yet it still has the same charter, tactics and goals.

4. The gray zone is where most damage occurs. Data laundering, third-party contractors, supply-chain manipulation, and ambiguous corporate partnerships allow intelligence extraction to look like ordinary business.

5. America’s innovation security gaps are systemic—not technical. Open research norms, VC incentives, distributed contracting, and hyper-globalized supply chains unknowingly subsidize Beijing’s industrial strategy. Over the air firmware updates to all your electronic devices keep it that way.

6. Protecting Silicon Valley innovation requires a new doctrine: innovation deterrence. Transparency in investment, hardened data flows, accountable supply chains, and elevated security standards for startups must become the baseline—not exceptions.

Conclusion

Silicon Valley was never supposed to become a battlespace. It was built on optimism, openness, and the assumption that technology financial markets reward merit, not manipulation. But Great Power Competition has rewritten the rules. The CCP’s strategy is not subtle—it is systemic. Through investment pipelines disguised as collaboration, talent programs disguised as opportunity, research partnerships disguised as scientific exchange, and gray-zone operations disguised as commerce, Beijing has embedded itself in the very place where America’s future is designed.

This report shows that innovation is now a contested domain. Not because engineers choose sides, but because adversaries exploit every seam—from university labs and AI incubators to venture capital networks and cloud infrastructure. China understands that whoever shapes the architectures of intelligence, autonomy, quantum capability, and synthetic biology will shape the 21st century. And so it courts the architects.

The United States cannot afford nostalgia. The old guardrails—trust-based partnerships, laissez-faire investment culture, open academic exchange—functioned in an era when adversaries moved slower, hid less well, and depended on kinetic theft instead of digital extraction. Today, the contest is fought through capital, data flows, talent pipelines, and invisible influence. The battlefield is quiet, but the stakes are seismic.

The path forward requires a shift in mindset: from protecting secrets to protecting systems, from reacting to espionage cases to anticipating the structural incentives that make them possible, and from treating Silicon Valley as a commercial ecosystem to recognizing it as a strategic asset essential to American power. If the 20th century was defined by nuclear deterrence, the 21st will be defined by innovation deterrence—our ability to safeguard the ideas that will govern global order for decades to come.

The world’s great powers are already fighting for the future. Silicon Valley is where much of that future is being written.

Additional Information

Sources, Acknowledgements and Image Credits

{1} China in Silicon Valley is an Expert Network Report researched and written by PWK International Managing Director David E. Tashji November 09, 2025. (C) 2025 PWK International.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, or academic work, or as otherwise permitted by applicable copyright law.

“China in Silicon Valley” and all associated content, including but not limited to the report title, cover design, internal design, maps, engineering drawings, infographics and chapter structure are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use, adaptation, translation, or distribution of this work, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.

This report is a work of non-fiction based on publicly available information, expert interviews, and independent analysis. While every effort has been made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any employer, client, or affiliated organization.

All company names, product names, and trademarks mentioned in this report are the property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. No endorsement by, or affiliation with, any third party is implied.

{2} Americas Innovation Corridor | California and Nevada. Map Credit: PWK International November 8, 2025.

{3} Why Silicon Valley. Map Credit: PWK International November 6, 2025.

{4} Additional Sources:

| Case | Description and Links |

|---|---|

| Chenguang Gong – San Jose / Southern California engineer | San Jose resident pleaded guilty to theft of trade secrets related to missile-detection and hypersonic-tracking tech for the benefit of China. Department of Justice+1 |

| Linwei “Leon” Ding – Google engineer, California | Former Google engineer indicted for stealing AI-chip and TPU design trade secrets and working with PRC companies. Department of Justice+1 |

| Liming Li – Rancho Cucamonga, California | Man pleaded guilty to possessing U.S. employer’s sensitive technology and marketing a competing company in China. Department of Justice |

| Chinese nationals charged as agents of PRC (California location) | Two Chinese nationals in California were charged with acting as agents of the PRC government, recruiting U.S. military personnel and gathering intelligence. Department of Justice+1 |

| US Navy sailor Jinchao “Patrick” Wei – Naval Base San Diego | U.S. Navy sailor stationed in San Diego convicted of espionage and export violations to China. Department of Justice+1 |

| Trade-secret theft from Silicon Valley companies (Cupertino/San Jose area) | Indictment of two California residents (Cupertino/San Jose) alleged to take trade secrets from four Silicon Valley companies and transfer them to PRC. IP Mall |

| Chinese national residing in California indicted for AI trade secrets from Google | Major case highlighting China’s focus on AI and Silicon Valley hardware/architecture theft. Department of Justice+1 |

| California digital-asset investment-scam with Chinese nexus | CA man sentenced for role in global digital-asset investment scam that involved illicit flows and foreign actors. Although not purely China tech espionage, useful for showing cross-sector financial vulnerability. Department of Justice |

| Suspected Chinese spy targeted California politicians (Bay Area influence operations) | Media reporting on a suspected Chinese spy targeting California politicians and conducting influence operations in the Bay Area. Axios |

| DOJ tech-theft enforcement across U.S., including California cases | Broad DOJ enforcement post documenting tech theft cases involving China and California firms. Good for contextualizing pattern. Axios |

About PWK International

PWK International is a strategic research and national security advisory firm specializing in the intersection of advanced technology, geopolitics, and the business of government. We serve clients across the innovation and defense ecosystem—including technology startups, established contractors, investment firms, expert networks, and organizations seeking decision-grade insight into how emerging technologies and great-power competition are reshaping global markets.

Drawing on decades of firsthand experience inside the U.S. government’s science and security enterprise, PWK International delivers high-impact analysis, briefings, and tailored advisory support that help leaders anticipate risk, identify opportunity, and navigate complex government landscapes. Our work blends investigative research, strategic storytelling, and big-idea thinking to illuminate the forces driving the next era of American power and technological competition.

Pingback: Venture Backed Arsenal |