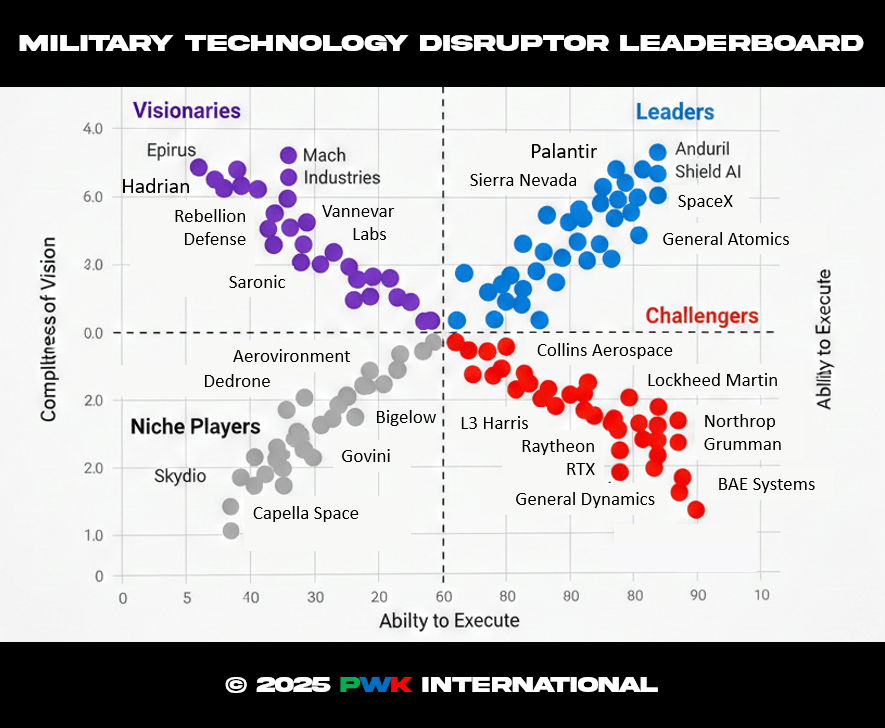

The U.S. defense sector is undergoing its most profound transformation since the early Cold War, and surprisingly, the epicenter isn’t a Pentagon program office—it’s a cluster of venture-backed startups operating with Silicon Valley speed. Companies like Anduril Industries, Palantir, Shield AI, Epirus, and Vannevar Labs have fused software-native thinking with aggressive capital, forming what many now call the PayPal Mafia of Defense. They are overturning decades of procurement bureaucracy and forcing the traditional primes—Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, RTX, General Dynamics, and BAE Systems—to confront a new, uncomfortable reality: innovation is no longer synonymous with size, secrecy, or multibillion-dollar cost-plus contracts.

Unlike the legacy players who mastered the art of navigating legendary bureaucracy, compliance regimes and congressional politics, these venture-backed entrants behave like asymmetric technology insurgents. They iterate in months, not decades. They ship minimum viable products into live operational environments. They build autonomy stacks and AI-driven sensor fusion platforms at a cadence the Pentagon is unaccustomed to. Their operating philosophy echoes early Silicon Valley—run fast, break things, learn, adapt, and scale. This report offers an assessment of that cultural collision and why it matters now.

At stake is not simply a procurement debate—it is the future architecture of American military power. As the United States confronts pacing threats from China, unpredictable gray-zone challenges from Russia and Iran, and rapidly evolving operational domains from cyber to space to autonomy, the old acquisition model looks dangerously mismatched to the moment. The emerging wave of defense innovators argues that speed, software, and constant iteration are no longer aspirational—they are now strategic imperatives. This report will examine how these new entrants are rewriting the rules of engagement for defense innovation and reshaping the expectations of senior leaders, combatant commands, soldiers and policymakers.

For technology experts, policy makers, investors and operators navigating this moment of transition, the stakes are unusually high. The defense-industrial base that wins the next decade will be the one that marries agility with reliability, open architecture with security, and commercial-grade development velocity with military-grade lethality. The companies redefining that balance are not the familiar giants of the past—they are the new insurgents building the arsenal of the future.

The Old World: How Legacy Primes Won (and Lost) the Last 40 Years

For decades, the center of gravity in the U.S. defense-industrial base rested firmly with a small group of legacy contractors who mastered the traditional acquisition system. Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, RTX, General Dynamics, and BAE Systems did not simply build platforms—they built ecosystems of political influence, regulatory expertise, and generational program entrenchment. Their competitive advantages were forged inside the rules of cost-plus contracting, sprawling systems-integration programs, and the Pentagon’s appetite for risk reduction over speed. The result was an environment where mastery of compliance, configuration control, and certification mattered more than disruptive engineering. In that world, innovation was measured not by iteration cycles but by milestones, gate reviews, and congressional appropriations that went up and down.

The foundational logic of the primes’ dominance rested on programs so large and so complex that only a handful of companies could execute them. Aircraft carriers, ballistic missile submarines, stealth bombers, nuclear command-and-control networks, and strategic missile architectures shaped a landscape where competition was rare and consolidation was inevitable. Multi-decade development timelines hardened into institutional norms: the F-35 took nearly 20 years to reach maturity; Columbia-class submarines are on a 20-year development cycle; even incremental upgrades often require 10-year planning horizons. These systems demanded bureaucratic expertise, not velocity. The primes became less about invention and more about stewardship—monopolies of stability.

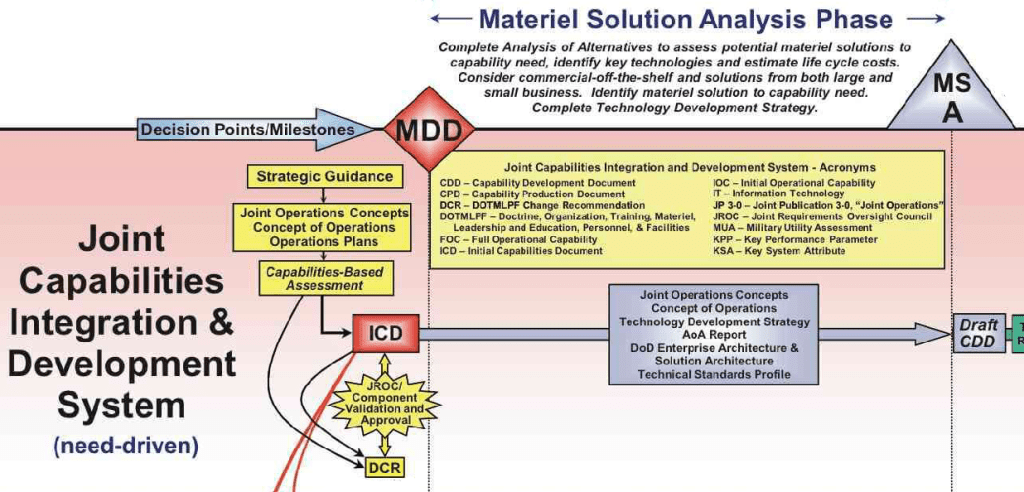

CAPTION: The Material Development Decision (MDD) is the initial and most critical decision point in the defense acquisition system, determining if a program's material is ready to move from the analysis phase to the development phase. It assesses if a need exists, if it's affordable, and if the technology is mature enough. The FAR (Federal Acquisition Regulation) sets the overarching rules for most federal agencies, while the DFARS (Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement) supplements the FAR with specific, additional requirements for the Department of War.

Over time, this structure produced a paradox. The primes delivered extraordinary engineering feats—stealth aircraft, strategic deterrence systems, and integrated missile defense networks—but they became structurally resistant to rapid technological change. Software modernization lagged, autonomy remained aspirational, and digital engineering was bolted onto legacy workflows rather than embedded from the start. The rise of cyber threats, hypersonics, electronic warfare agility, and AI-enabled targeting exposed vulnerabilities that could not be solved with bigger contracts or longer timelines. For years, the Pentagon tolerated these frictions because there were no credible alternatives.

That world no longer exists. The speed of modern conflict—especially against near-peer adversaries—has made the traditional defense-industrial playbook unsustainable. China iterates weapons systems faster than the United States certifies them. Russia adapts electronic warfare techniques inside operational theaters in real time. Attribution in cyber conflict is measured in minutes, not months. Against this backdrop, the primes’ model of decades-long development cycles has become a strategic liability. Into this moment stepped a new generation of firms that did not inherit the old rules, did not fear the old constraints, and did not depend on congressional inertia to survive. They brought speed, software, autonomy, and commercial capital—and they forced the Pentagon to recognize that the old world, for all its engineering triumphs, was losing the race against time.

CAPTION: The milestone A to B technology development phase is also known as the Technology Maturation and Risk Reduction (TMRR) phase, which follows Milestone A approval. Milestone B is the subsequent milestone that marks the decision to enter the Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) phase. This transition is approved after a successful review at Milestone B and is critical for proceeding with the full system design and development.

The Rise of the Venture-Backed Arsenal

The collapse of the old innovation tempo created a vacuum, and Silicon Valley seized it with uncharacteristic focus. A new cohort of companies—Anduril, Palantir, Shield AI, Epirus, Hermeus, Vannevar Labs, Hadrian, Saildrone, among others—entered the defense sector not as niche subcontractors, but as potential modern primes. Their emergence coincided with a tectonic shift in venture capital: for the first time since the dot-com era, top-tier funds were willing to deploy serious capital into national security. Founders Fund, a16z’s American Dynamism, Lux Capital, Snowpoint, and Shield Capital collectively injected billions into firms that viewed defense not as a burdened market, but as an existential one. The result was an industrial insurgency—a portfolio of fast-moving startups treating defense like a commercial sector where speed, productization, and iteration were not only possible but required when the mission is to prevent world war three.

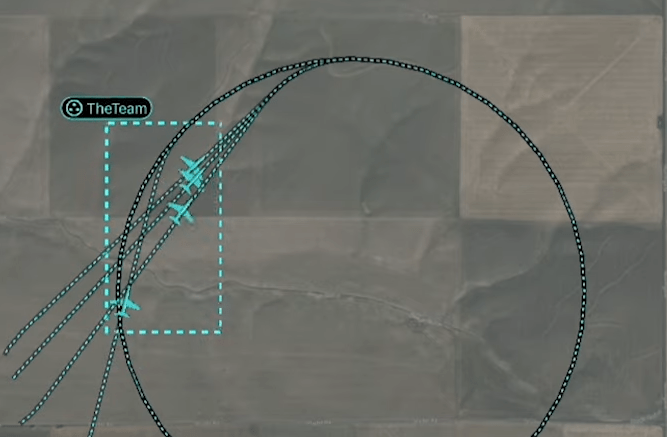

These firms operate on a fundamentally different philosophy. Rather than designing bespoke hardware for isolated programs of record, they build productized stacks: autonomous systems, AI frameworks, multi-domain sensing platforms, digital command-and-control systems, and software-defined weapons. Their business model mirrors the cloud-software world: develop a core platform, deploy early, gather feedback, refine relentlessly, and scale horizontally across missions. Lattice from Anduril, Gotham and Foundry from Palantir, Hivemind from Shield AI, and the software-defined high-power microwave architecture from Epirus are not traditional “program deliverables”—they are continuously evolving operating systems for the battlefield. These companies sell capability, not compliance.

The shift is not just technical—it’s cultural. Silicon Valley’s operating tempo stands in direct opposition to the risk-averse traditions of the defense marketplace. These new firms ship updates weekly, not annually; field prototypes in active theaters; rely on flat organizational structures; and empower engineering teams to push capability directly to the edge. Their founders often possess backgrounds that combine commercial software experience with national security exposure—an unusual fusion that lets them speak fluently to both worlds. Their worldview is mission-first, bureaucracy-second. They believe deterrence depends on iteration cycles, not milestone reviews. And they believe the military deserves technology that evolves at the speed of the threat, not the speed of the FAR.

Yet their rise is not simply the result of engineering prowess—it is the consequence of a Pentagon increasingly aware that the legacy model cannot outpace China’s state-directed innovation machine, much of it stolen from US Technology Companies, Universities and Government Research Labs.

As DoD leaders embraced OTAs, middle-tier acquisition pathways, commercial solutions openings, and software acquisition reform, they created the legal and cultural space necessary for startups to compete with the primes. In that newly opened aperture, venture-backed defense firms found the opportunity to deliver working capability directly to warfighters, bypassing traditional bottlenecks. They became proof of concept that a faster, software-driven, autonomy-centric industrial base is not hypothetical—it is already here, scaling, and reshaping what American military power looks like in the 21st century.

CAPTION: Adaptive acquisition is the U.S. Department of War framework that uses different, tailored pathways to acquire capabilities, unlike a one-size-fits-all approach. Major Capability Acquisition (MCA) is for long-term, complex, exquisite systems like an aircraft carrier or ballistic missile submarine, while Software Acquisition is a separate pathway focused on rapid, iterative, and agile software development and delivery. Additional pathways exist for a Defense Business System that supports multi-factor authentication (CAC Card Readers) and for Acquisition of Services such as outsourced security forces at black budget test range or special access only sites.

How the PayPal Mafia of the Defense Industry Wins

The success of the new defense entrants is not accidental—it is structural. Their competitive advantage begins with a simple premise: software, not hardware, is now the center of gravity in modern warfare. In conflicts where kill chains unfold in seconds, not minutes, and where sensors, shooters, and decision-makers must function as an integrated whole, the side with the superior software pipeline dominates. Silicon Valley–born firms thrive in this environment because they treat software as a living system rather than a static deliverable. They enforce continuous integration, real-time telemetry, automated testing, and rapid deployment cycles. In an era where algorithmic warfare, electronic agility, and AI-driven autonomy define mission success, the companies that iterate fastest are the ones that win.

Another source of advantage is their commitment to vertically integrated autonomy stacks. Instead of segmenting sensing, fusion, autonomy, and mission applications across a complex web of subcontractors, these companies build end-to-end architectures under one roof. Anduril designs sensors, platforms, AI models, and its Lattice operating system as a unified ecosystem. Shield AI trains its Hivemind autonomy on diverse platforms—from quadcopters to F-16 surrogates—without rewriting its foundation. Palantir integrates data engineering, analytics, and operational AI in a modular but coherent suite. This verticality accelerates fielding, reduces integration friction, and enables the rapid deployment of new mission profiles. It mirrors Apple’s ecosystem thinking: controlled integration yields superior reliability, faster iteration, and deeper user trust.

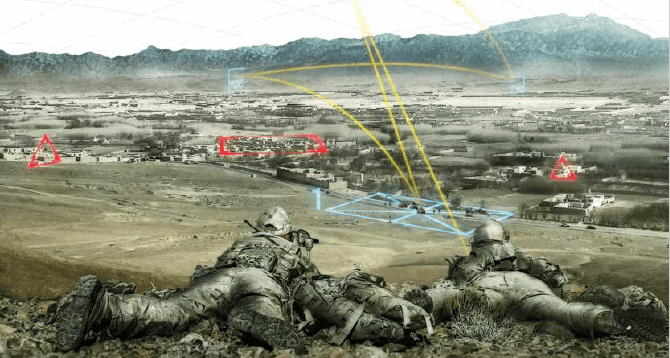

Speed itself becomes a warfighting variable. The new primes view rapid deployment as a strategic imperative—not a performance metric. They thrive in real-world environments: U.S. Southern Command’s maritime ISR gaps, Indo-Pacific contested logistics challenges, CENTCOM’s counter-UAS missions, and European integrated air defense modernization. Their philosophy is simple: the field is the laboratory, the warfighter is the customer, and deployment is the first version—not the final one. Instead of waiting for block upgrades, they push capability updates weekly, even daily. In an era of dynamic EW environments, drone swarms, and adversaries who adapt in real time, this tempo becomes decisive.

Finally, the new primes scale through networks, not platforms. Legacy primes built massive, exquisite systems that dominated single mission areas; the new entrants build interconnected systems that flex across domains. Their architectures are modular, open, and data-centric—designed to plug into JADC2, Project Overmatch, ABMS, and emerging coalition architectures. They are not competing to build the next fighter jet or aircraft carrier—they are competing to build the connective tissue that binds everything else together. The advantage is clear: platforms age, but networks evolve. In this paradigm, the winners are not those who manufacture the largest hardware, but those who deliver the most adaptable operating system for the future of conflict.

Incumbents and the Legacy Primes

The rise of venture-backed defense innovators has not gone unnoticed by the traditional primes. In fact, the last five years have triggered the most aggressive strategic repositioning inside legacy contractors in decades. Many primes are attempting to replicate the startup model through acquisition and partnership strategies. L3Harris became one of the most active consolidators, absorbing aero-autonomy, sensor, and communications companies to broaden its portfolio. RTX and Lockheed increasingly pursue partnerships with software-native firms rather than build everything in-house. Some primes have quietly launched internal “fast cells”—small, semi-autonomous development units freed from the bureaucracy of the main enterprise and tasked with producing capability at commercial speed. These initiatives are not simply about modernization—they are about survival. The primes understand that if they cannot match the agility and software velocity of the new entrants, their position as program integrators will erode..

Despite these challenges, the primes retain formidable advantages—and they are weaponizing them. They control deep manufacturing capacity, certification pathways, secure facilities, classified program expertise, and long-standing relationships with Congress and the Pentagon. No startup can replace the industrial base required to build nuclear submarines, hypersonic weapons, space architectures, or missile defense networks. The future therefore points toward a hybrid competitive environment: insurgent startups driving speed, software, and autonomy at the tactical edge, while legacy primes anchor strategic production and large-scale integration. The firms that thrive will be those that can operate across this divide, merging the agility of the new world with the industrial backbone of the old.

The Pentagon at a Crossroads

The Department of Defense now sits at the fulcrum of two competing industrial paradigms—one optimized for stability and scale, the other for speed and disruption. Senior leaders know the geopolitical environment demands faster capability delivery, yet the Pentagon’s internal machinery still reflects decades of culture built around program-of-record thinking. Requirements processes remain slow, budget cycles remain rigid, and oversight mechanisms—designed to prevent failure—often prevent progress. The rise of commercial dual-use technology and venture-backed defense firms has forced the Pentagon to confront a question it has avoided for 40 years: Can a bureaucracy built for the Industrial Age adapt to a software-defined battlespace? The answer will shape America’s technological edge for decades.

To its credit, the DoD has begun to implement new pathways that break from legacy procurement models. The adoption of OTAs, Middle-Tier Acquisition authorities, and Software Acquisition Pathways signal a structural shift toward iterative development. Organizations like the Defense Innovation Unit, AFWERX, NavalX, Army Applications Lab, SCO, and the Chief Digital and AI Office have emerged as connective tissue between the Pentagon and the startup ecosystem. Combatant Commands—especially INDOPACOM and CENTCOM—have become significant adopters of rapid-deployment technologies, proving that field-driven demand can accelerate adoption when the bureaucracy cannot. These mechanisms are imperfect, but they represent a recognition that the future of deterrence depends on speed, not paperwork.

The Department of War’s new Acquisition Transformation Strategy aims to accelerate the development and delivery of new military capabilities by prioritizing speed, commercial solutions, and flexibility over traditional, slower processes. Key components include streamlining regulations, establishing Portfolio Acquisition Executives with more authority, prioritizing commercial-first approaches, and taking a “risk-acceptance” approach to get technology to warfighters faster. This overhaul also seeks to rebuild the defense industrial base and use more non-FAR-based contracting instruments like Other Transaction Authorities (OTAs) to bypass traditional constraints.

Still, the Pentagon struggles with contradictions of its own making. It demands cutting-edge AI and autonomy but often insists on procurement processes designed for aircraft carriers. It wants modular, open architectures but occasionally allows entrenched vendors to lock down the very interfaces needed for interoperability. It asks for commercial innovation but requires compliance burdens no commercial startup can endure at scale. The result is a bifurcated ecosystem: programs of record governed by 20th-century rules, and rapid experimentation cells operating in 21st-century reality. Bridging that divide is the central acquisition challenge of the decade, and without deliberate structural change, the gap between innovators and integrators will continue to widen.

The future of U.S. military competitiveness hinges on whether the Pentagon can institutionalize a new model—one that blends the reliability of the legacy primes with the velocity of the venture-backed arsenal. This requires more than granting new authorities; it requires rethinking incentives, redefining requirements, rewiring digital infrastructure, and empowering program managers to take smart risks. The DoD must shift from “buying systems” to “buying software ecosystems,” from “preventing failure” to “accelerating learning,” from “multi-decade programs” to “continuously evolving capabilities.” If it succeeds, America will retain its strategic edge against China’s state-driven innovation machine. If it fails, the United States will enter the next conflict with technology designed for a world that no longer exists.

The Collision: When Agile Meets the Pentagon

The defining tension of modern defense innovation is the collision between Silicon Valley’s agile development model and the Pentagon’s deeply institutionalized acquisition architecture. Agile thrives on continuous delivery, rapid iteration, and the freedom to rewrite requirements based on real-world feedback. The Pentagon, by contrast, was built around a linear, deterministic process—requirements first, design second, testing third, production last. These two cultures do not merely diverge; they contradict each other. When a venture-backed firm arrives with a working prototype built in six months, the system frequently responds by asking for documentation, compliance artifacts, and milestone certifications that assume such speed is impossible. The result is friction that slows innovation even when capability is already in hand.

This cultural mismatch is most visible in how each side interprets risk. Agile assumes risk is inherent and manageable through rapid iteration—fail quickly, learn immediately, deploy again. The Pentagon treats risk as something to be minimized through planning, oversight, and layers of approval. For a software-native company, deploying a new autonomy model weekly is normal. For a traditional acquisition office, deploying anything without a full test campaign can feel reckless. This conflicting risk calculus explains why many cutting-edge systems from startups are proven in combat zones before they are ever approved through conventional procurement channels. The battlefield becomes the validator, not the bureaucracy, because the bureaucracy is not structured to validate rapid change.

Another point of collision is the concept of ownership. Startups build modular, productized systems with continuous updates tied to recurring software licenses. The Pentagon, however, grew up purchasing systems as one-time capital assets—buy it, own it, control it. This legacy mindset clashes with platforms like Lattice, Palantir’s Foundry, Shield AI’s Hivemind, or Epirus’s software-defined weapons, all of which rely on perpetual iteration. When the Pentagon demands full technical data rights or government-purpose rights for systems designed to evolve like commercial software, it inadvertently undermines the very innovation it seeks. The question becomes existential for modern defense tech: does DoD want to own the code, or does it want to own the capability? Those are no longer the same thing.

Yet despite these structural tensions, the collision is also generating progress. Combatant Commands are increasingly bypassing traditional pathways to field new technologies quickly. OTA consortia allow software-driven firms to deliver capability in months, not years. Cross-functional teams are emerging to break down silos, and new acquisition pathways allow pilots to scale into programs of record. The friction has not disappeared—but it is being managed more strategically. In the long run, the collision between agile and the Pentagon is not a crisis; it is the crucible from which the next-generation defense-industrial base will be forged. The institutions that adapt will thrive. Those that cling to legacy processes will become irrelevant as the speed of threat evolution accelerates.

Case Studies: Anduril and Palantir

Few companies embody the tectonic shift in modern defense innovation as powerfully as Anduril Industries and Palantir Technologies—two firms that did not wait for permission to challenge the legacy defense-industrial ecosystem. Each represents a distinct archetype of the new defense prime: Anduril as the insurgent hardware–software hybrid reinventing autonomy at scale, and Palantir as the data-driven operational nerve center that forces lethargic institutions to rethink the tempo of command.

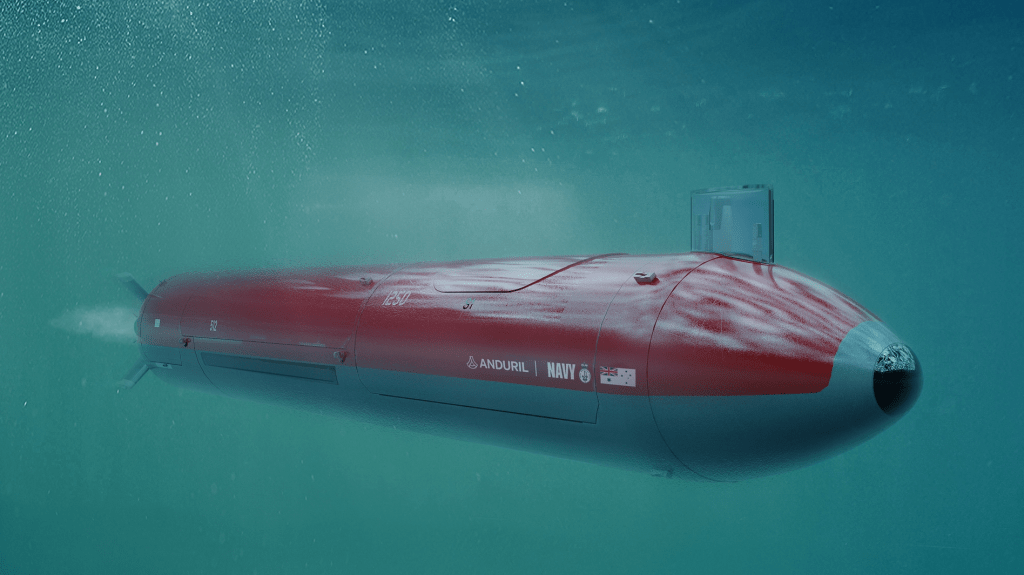

Anduril’s growth reflects a deliberate strategy to short-circuit the traditional procurement treadmill. By developing complete, vertically integrated systems—from Lattice OS to autonomous drones to counter-UAS towers—the company behaves like a 21st-century Lockheed Martin that happens to move at Silicon Valley speed. Its defining bet has been autonomy as a force multiplier: pairing inexpensive, attritable platforms with an AI core that can detect, decide, and act faster than human-centric kill chains ever could. Anduril’s work on counter-drone systems, undersea vehicles, and autonomous battle networks illustrates how a commercial technology mindset can rewrite the cost curve of defense. In an era of saturation attacks and contested spectrum, Anduril is effectively writing the doctrine for how machines fight.

Palantir, in contrast, focuses on the upper brainstem of modern conflict: decision advantage. Its platforms—Gotham, Foundry, and AIP—did not evolve as mere data tools but as engines for operational truth in environments where the price of uncertainty is measured in casualties. Palantir’s presence in Ukraine became a proof point: intelligence fusion, targeting optimization, and logistics forecasting that collapsed multi-day analytical tasks into minutes. What makes Palantir dangerous to legacy primes is not just its speed; it’s its direct relationship with commanders. Palantir bypasses intermediaries, reinvents workflows, and forces bureaucracies to admit that the future belongs to systems that learn faster than they can write RFPs. The company’s rise exposes the essential flaw in “requirements-first” procurement: the battlefield refuses to wait for paperwork.

Together, Anduril and Palantir demonstrate the arrival of a new model of defense partner—one that blends commercial velocity with national-security seriousness, strategic patience with rapid iteration, and mission alignment with technological boldness. They are not merely vendors; they are doctrine-shaping institutions. Their systems challenge the Pentagon to adapt or become strategically irrelevant. More importantly, they reveal a path forward for the broader defense ecosystem: value comes from those who can build, test, deploy, and evolve faster than adversaries can copy. In their success lies a roadmap for the next generation of defense innovators—and a warning to every traditional prime still operating on Cold War timelines.

Strategic Implications for the Defense Primes

The rise of firms like Anduril and Palantir has forced the Big Five defense primes—Lockheed Martin, Raytheon, Northrop Grumman, Boeing, and General Dynamics—to confront a strategic inflection point. For decades, these companies perfected a model centered on multidecade programs, hardware dominance, and cost-plus contracting. That model built the world’s most formidable military, but it now collides with a strategic environment defined by speed, software, and distributed autonomy. The challenge is not existential—but it is cultural. The primes now operate in a market where their historical advantages no longer guarantee future relevance, and where their size, once an asset, increasingly behaves like a tax on innovation.

The first implication is the shift from platform-centric thinking to network-centric warfare. The primes traditionally optimized for exquisite platforms—F-35s, Aegis destroyers, missile silos, stealth bombers. But autonomy, AI-driven sensing, and machine-speed command-and-control invert the logic: value now accrues to the connective tissue, not the airframe. That means the Big Five must rethink their core identity. Are they builders of machines, or architects of kill webs? Do they continue to emphasize billion-dollar platforms, or do they embrace the future of thousands of cheap, intelligent, distributed systems? The companies that fail to answer this question will find themselves outmaneuvered by smaller firms that can produce iterative, networked capabilities without waiting for the next major Pentagon reprogramming action.

The second implication is the collapse of barriers between software and hardware, a trend that has historically challenged the primes. Anduril and Palantir both thrive because they start with software-first architectures that pull hardware into their orbit—or bypass it altogether. In contrast, the primes often treat software as a bolt-on, managed through sprawling subcontractor chains that slow delivery and dilute accountability. To remain competitive, they must adopt vertically integrated software development models that mirror the speed of commercial engineering. That means owning core codebases, embracing continuous deployment, and shifting from bespoke systems to modular, upgradeable architectures. This transition is not cosmetic; it is existential. Software-defined warfare requires software-native primes.

The final implication is strategic positioning: the Big Five must decide whether to compete with the new entrants or collaborate with them. The market is already forming hybrid ecosystems where primes supply industrial capacity and manufacturing scale, while firms like Anduril and Palantir supply the AI core, autonomy stack, and data fusion engines. The primes that embrace these partnerships will gain access to capabilities they cannot replicate internally at speed. Those that resist will slowly drift into irrelevance as integrators of yesterday’s technologies. The future of defense will belong to companies that can operate with the agility of startups, the discipline of major primes, and the operational focus of wartime engineers. The Big Five still have the reach, capital, and political presence to dominate—but only if they accept that the era of slow, sequential acquisition is over, and that strategic relevance now depends on how fast they can learn.

What This Means for the U.S. Military

The shift toward venture-backed, software-native defense firms carries profound operational implications for the U.S. military. At its core, it signals a move away from platforms as the centerpiece of capability toward adaptive, networked systems that can be updated continuously in theater. From autonomous drones and sensor grids to AI-enabled targeting and decision support, military units now have the potential to access capabilities that evolve at the speed of conflict. The emphasis is no longer on waiting years for a block upgrade; it is on integrating modular systems that can respond to emerging threats in real time, fundamentally altering the tempo and character of operations.

This evolution also impacts training, doctrine, and force design. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines must become comfortable with autonomous decision aids, AI-driven mission planning, and rapidly iterating software tools. Units will increasingly operate as nodes within broader distributed networks, where decision advantage derives not from individual platforms but from the ability to act collectively and intelligently across domains. Traditional hierarchical command structures may need adaptation, as the speed of automated systems will often outpace human deliberation. The military must embrace a culture of experimentation and iterative learning, recognizing that agility and adaptability are as critical as firepower.

The integration of these new technologies also changes strategic calculus. Faster deployment of autonomous, AI-enabled systems enhances deterrence by compressing decision cycles and complicating adversary planning. It allows for more resilient, attritable systems that can sustain operations under attack, reducing reliance on expensive, high-value platforms. Furthermore, software-defined architectures create opportunities for coalition interoperability, giving the United States and its partners a decisive advantage in multi-domain operations. Conversely, failure to adapt risks ceding initiative to competitors who embrace speed, autonomy, and networked lethality.

Finally, the U.S. military must contend with organizational and acquisition challenges that accompany this technological shift. Legacy contracting, budgeting, and compliance processes are poorly aligned with iterative, software-driven development cycles. Integrating small, agile startups into traditional programs of record requires new acquisition strategies, clear IP frameworks, and a willingness to delegate operational authority to commercial partners. Success will depend on the military’s ability to institutionalize rapid experimentation without compromising reliability or security, ensuring that technological advantage translates into operational dominance. Those forces that can bridge the cultural and procedural divide between the old and new defense ecosystems will define the battlefield of the next decade.

Conclusion — The Arsenal Reborn

The U.S. defense-industrial base is entering an era defined not by size, secrecy, or program longevity, but by speed, software, and the ability to iterate in real time. Venture-backed companies like Anduril, Palantir, Shield AI, and Epirus have demonstrated that a small, agile, software-first approach can produce operationally relevant systems faster than decades-long programs. These firms are not just delivering technology; they are reshaping doctrine, redefining industrial norms, and challenging entrenched assumptions about how military power is built, sustained, and projected. The battlefield has become a laboratory, and the laboratory has become a force multiplier.

This transformation represents both opportunity and risk. The Pentagon and traditional primes can harness these innovations to accelerate capability delivery, integrate autonomous and AI-enabled systems, and maintain a decisive advantage against near-peer competitors. Yet the collision of cultures—entrepreneurial agility versus bureaucratic rigor—requires deliberate management. Speed alone does not guarantee effectiveness, and technological novelty must be paired with operational discipline, systems integration, and long-term sustainment. The future will favor organizations that can merge the velocity of startups with the scale, reliability, and institutional knowledge of legacy primes.

The strategic implication is clear: the new arsenal is software-defined, autonomy-driven, and network-centric. Hardware remains important, but its value now derives from how it interacts with data, AI, and multi-domain networks. This paradigm enables faster fielding of capability, resilient distributed systems, and adaptive force structures that can operate under conditions of uncertainty. It also challenges the military to rethink requirements, command structures, and acquisition pathways to align with a world in which technological advantage accrues to the side that can learn, adapt, and iterate faster than its adversaries.

As the U.S. military confronts a rapidly evolving threat environment—from hypersonics and electronic warfare to cyber, space, and AI-enabled operations—the imperative is to embrace a hybrid industrial ecosystem. Startups bring speed, software, and innovation; primes bring scale, security, and lifecycle expertise. The collision of these worlds is the crucible in which the 21st-century arsenal will be forged. Those who can navigate it successfully will not only maintain technological superiority but will redefine what it means to wield military power in the modern era.

Top Six Takeaways

1. The Pentagon is at a crossroads – Successful adaptation requires cultural change, acquisition reform, and an institutional commitment to experimentation and learning at operational speed.

2. Speed over size – Agile, software-native firms are delivering capability faster than traditional cost-plus programs, changing the tempo of innovation and operations.

3. Software is the center of gravity – Autonomous systems, AI, and data-driven platforms now define the edge in multi-domain conflict.

4. Vertical integration wins – Companies that control both hardware and software stacks can iterate and deploy faster, reducing integration friction.

5. Networks outperform platforms – Modularity, interoperability, and system-of-systems thinking are replacing reliance on single, exquisite platforms.

6. Primes must adapt – Legacy contractors retain scale and political influence but must embrace agility, software ownership, and partnerships with startups to remain relevant.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

BILLIONAIRES

AT WAR

HIGH STAKES

AND HIGH NET WORTH

Sources, Acknowledgements and Image Credits

{1} Venture Backed Arsenal | Inside the PayPal Mafia of the Defense Industry is an expert network report researched and written by PWK International Managing Director David E. Tashji. (C) 2025 PWK International. All Rights Reserved. Required Attribution: (C) PWK International 2025

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, or academic work, or as otherwise permitted by applicable copyright law.

“Venture Backed Arsenal” and all associated content, including but not limited to the report title, cover design, internal design, maps, engineering drawings, infographics and chapter structure are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use, adaptation, translation, or distribution of this work, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.

This report is a work of non-fiction based on publicly available information, expert interviews, and independent analysis. While every effort has been made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any employer, client, or affiliated organization.

All company names, product names, and trademarks mentioned in this report are the property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. No endorsement by, or affiliation with, any third party is implied.

{2} Our un-biased report includes mention of numerous investment firms, technology disruptors and their battlefield advantage innovations. All registered trade marks and trade names are the property of the respective owners.

{3} TechCrunch – Led by Anduril, defense tech funding sets a new record TechCrunch

{4} CNBC – Anduril raises funding at $30.5 billion valuation CNBC

{5} Fortune – With massive funding round and $31B valuation, Anduril nears size of defense giants Fortune

{7} FinSMEs – Anduril Industries raises $1.48B in Series E FinSMEs

{8} Defense News – Defense tech firms establish AI-focused consortium (Palantir & Anduril) Defense News+1

{9} Defense One – Are AI defense firms about to eat the Pentagon? Defense One

{10} Reuters – Anduril and Palantir battlefield communication system has deep flaws, Army memo says Reuters

{11} Palantir Investor Relations – Army Awards Palantir AI/ML Contract in Support of JADC2 Palantir Investors

{12} National Defense Magazine – With foundations laid, Pentagon building CJADC2’s data backbone National Defense Magazine

{13} Defense Scoop – Palantir partners with data-labeling startup to improve AI models DefenseScoop

{14} C4ISRNET – Palantir: With Joint All-Domain Command and Control, the Pentagon is finally catching up C4ISRNet

{15} Defense News – Palantir delivers first 2 next-gen targeting systems (TITAN) to U.S. Army Defense News

{16} Breaking Defense – Palantir wins contract for Army TITAN next-gen targeting system Breaking Defense

{17} arXiv (Academic) – AI-Driven Tactical Communications and Networking for Defense: A Survey and Emerging Trends arXiv

About PWK International

PWK International is a strategic consulting firm specializing in advanced technology innovation, defense modernization, and government operations. Leveraging decades of experience across the defense-industrial base, PWK International helps clients navigate the intersection of commercial technology, venture-backed innovation, and traditional government programs. The firm’s expertise spans software-driven autonomy, AI-enabled decision systems, unmanned platforms, and advanced sensor networks, offering actionable insights to organizations seeking to accelerate capability delivery in a rapidly evolving operational environment.

This report reflects PWK International’s commitment to translating complex technological and organizational trends into strategic intelligence for decision-makers. PWK International serves a diverse and highly specialized client portfolio and provides unparalleled guidance on integrating software-native capabilities, autonomous systems, and networked architectures into existing programs of record and strategic roadmaps.

PWK International’s approach combines rigorous analysis with practical implementation. The firm helps clients understand emerging threats, optimize acquisition strategies, and align innovation initiatives with operational priorities. By providing insight into the cultural, structural, and technological shifts shaping the defense landscape, PWK International ensures its clients remain ahead of both adversaries and competitors.

Whether advising government leaders on acquisition reform, guiding primes on modernizing legacy systems, or helping startups scale rapidly to meet operational needs, PWK International delivers the strategic clarity and domain expertise necessary to succeed in the next generation of defense innovation.

Pingback: Unfair Fights |

Pingback: Billionaires at War: High Stakes and High Net Worth |