Unfair fights are no longer hypothetical—they are the operating systems of modern conflict. Adversaries mass cheap improvised munitions, saturate sensors, infiltrate supply chains, attack decision cycles and manipulate with ruthless precision the cost curve in the war between the factories. This report offers an assessment of our new “cheaper is better” reality in modern conflict where the battlefield is no longer defined by technological parity, but by deliberate and economic asymmetry. Across all domains and multiple theaters, adversaries have learned that overwhelming a defender does not require matching sophistication—only exceeding the defenders capacity to respond. This report will unpack how “unfair fights” have emerged as the dominant logic of modern warfare and what they reveal about the future of deterrence.

For decades, military planners assumed that superior sensors, interceptors, and integrated command-and-control networks would provide decisive advantage. The side with the sharper picture and the faster decision cycle would win. But today’s most disruptive actors have rewritten the rules. They have discovered that decision advantage cuts both ways: if you cannot defeat a high-end system head-on, you can diminish it from an unexpected attack surface or with asymmetrical cost burdens. Technological surprise still matters, but its most potent expression now comes not from exquisite capabilities—but from unexpected vectors and low cost volume.

Iran fires salvos of cheap drones padded with a handful of higher-end ballistic missiles. Russia saturates Ukrainian defenses with grim regularity—glide bombs, loitering munitions, and cruise missiles layered into coordinated waves. The Houthis launch in multi-vector patterns designed not to hit a target directly, but to drain interceptors from U.S. ships patrolling the Red Sea. And China’s Taiwan invasion concepts hinge on mass at extreme scale: thousands of missiles in the opening hour, aiming to blind, break, and bury any defensive architecture designed for more orderly wars.

The pattern is unmistakable. It is the exploitation of quantity—not quality—as a strategic weapon. Every Patriot shot costs roughly $4 million. Every Iranian Shahed drone costs around $20,000. One side fires the modern equivalent of lawnmower engines strapped to wings; the other expends precision-guided gold bars to stop them. This is not a symmetry of war. It is a strategy for bankrupting the defender long before the battlefield is lost.

Unfair fights are therefore not about matching strength with equal strength. They are about throwing punches far above their weight class, about leveraging the mathematics of mass and the economics of attrition. They expose a hard truth: in the age of abundant drones, cheap manufacturing, and algorithmic targeting, the most dangerous adversaries are not necessarily the most advanced. They are the ones willing to make conflict economically irrational for everyone else.

This is the landscape this report will explore—where asymmetry is not the exception, but the strategy; where tactical volume becomes strategic advantage; and where the future of defense depends on rethinking a system never designed for the wars it now faces.

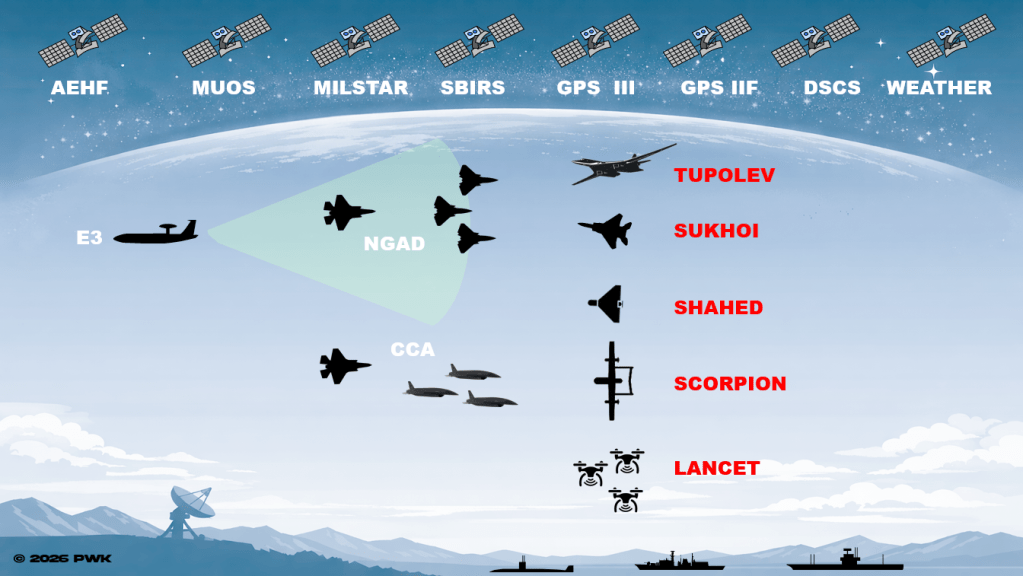

The Cold War model of a few exquisite platforms is giving way to distributed ecosystems where programs like Next Generation Air Dominance and Collaborative Combat Aircraft combine manned aircraft, autonomous systems, and space services like SBIRS and GPS III to operate as a networked force across air, land, sea, space and cyberspace. Explore how new math, bold ideas and venture capital speed are re-imagining affordable mass for the next era of conflict.

The Era of Unfair Fights

Sun Tzu wrote that the supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting; he might have added, if he lived in the twenty-first century, that the supreme art of strategy today is to make your opponent pay for every defensive breath he takes. Historically, unfairness in war tended to run one way: stronger states crushed weaker ones through superior numbers, organization, and logistics. Missile- and drone-era warfare inverted that logic. For the first time in modern history, weak actors routinely impose catastrophic economic and political costs on far wealthier defenders by weaponizing abundance, obscuring attribution, and exploiting the arithmetic of the “war between the factories”.

The mechanics are simple and brutal. Cheap, plentiful systems—whether kamikaze drones, short-range rockets, or improvised sea drones—create a problem of scale for high-end defensive architectures built around expensive interceptors, elaborate sensor nets, and centralized decision chains. Analytical work shows that the cost per strike for some kamikaze or loitering munitions is measured in the tens of thousands of dollars while the interceptors used against them can cost millions; in practice, adversaries can make defenders spend their way into strategic exhaustion. That arithmetic underpins the single most important tactical lesson of recent years: numerical saturation often defeats technical sophistication. CSIS

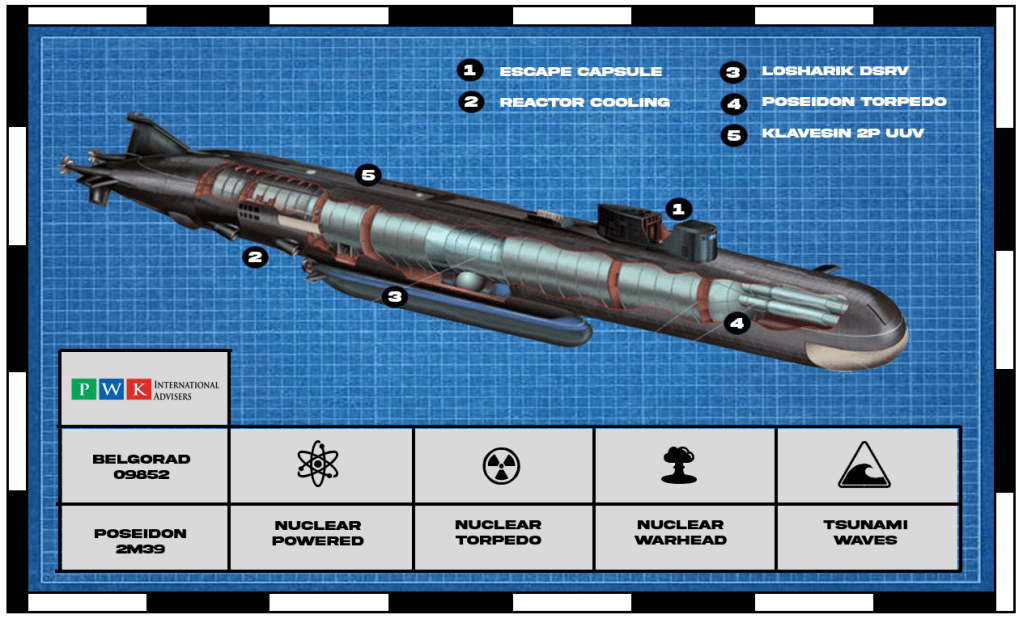

CAPTION: In this modern-day Hunt for Red October, the new contest includes harnessing the power of the planets oceanography to deliver multiple knockout blows without warning. The Belgorad and its Poseidon payload turn the deep ocean into a covert weapon system.

In this unfair fight, one side relies on fleets, undersea networks (SOSUS), and unmanned marine vessels; the other relies on synchronization and nuclear detonations that harness the raw power of the ocean itself. When stealth, zero warning, and planetary-scale water displacement form the attack profile, you don’t get a battle — you get GAME OVER.

CAPTION: Ukraine’s fiber-optic FPV drone is the rare battlefield invention that changes the math, not the map. What looks like a garage-built quadrotor is actually a precision sabotage system built around a 10-kilometer fiber-optic tether. No radio links. No datalinks. No jamming surface. To Russian EW units, it is invisible—a ghost on a string.

The warhead varies—thermite, shaped charge, improvised grenades—but the tactical brilliance is the control architecture. Operators guide the drone through hardened trenches, blind spots, and EW-saturated kill zones with millimeter accuracy. It cuts through “turtle tank” roof cages, drops charges into engine bays, and slips beneath overhead defenses that normally defeat FPVs.

In an unfair fight, this drone is the countermeasure to the countermeasure. When the electronic battlefield turns hostile, Ukraine simply removes electronics from the equation. It’s low-cost, unjammable, and psychologically devastating—proof that in modern war, the smarter system beats the stronger one.

Russia has responded with saturation strikes on Ukraine with integrated glide bombs, cruise missiles, and massed drone waves in coordinated attacks—sometimes numbering in the many hundreds of air-launched and surface-launched munitions in a single operation to overwhelm Ukrainian air-defense inventories and create persistent windows of vulnerability.

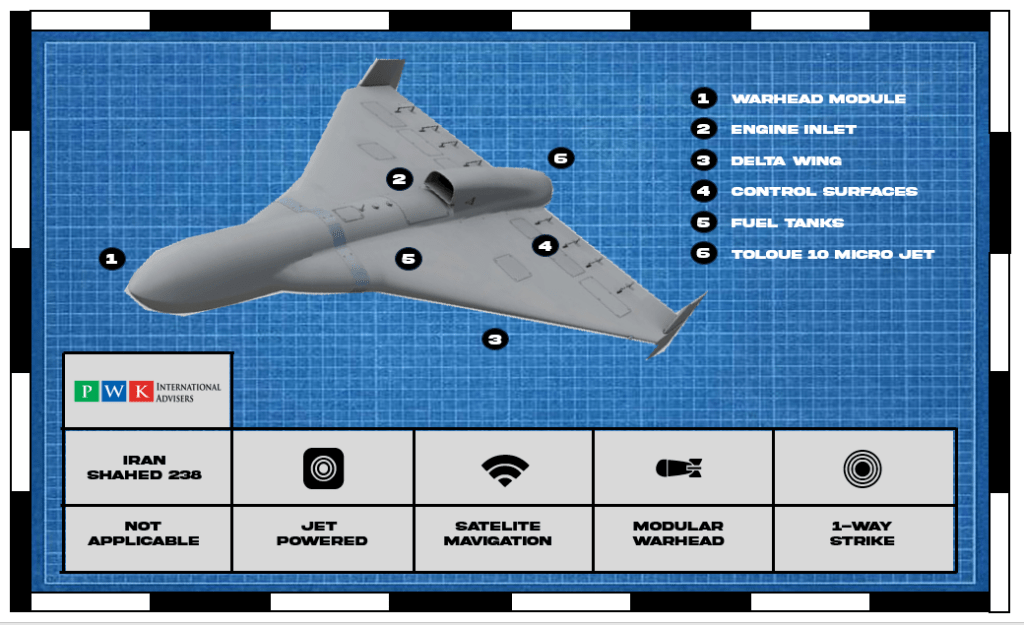

CAPTION: The Shahed-238 isn’t designed to win a dogfight—it's designed to overwhelm one. Iran’s jet-powered evolution of the Shahed line trades simplicity for speed, pushing estimated velocities into the 400–500 mph class, fast enough to compress defender decision-time to seconds. It carries a modest payload, but that’s not the point. The Shahed-238 is a pace-setter in a larger swarm: it forces air defenses to activate, expend interceptors, and reveal targeting radars.

In an unfair fight, it’s the opener in a layered, multi-vector saturation attack—launched alongside slow Shahed-131s, mid-range 136s, decoys, loitering munitions, and even ballistic-missile salvos. The jet variant’s role is simple: break timing, fracture attention, and widen the defender’s OODA loop.

Iran’s Shahed campaign began in the 2010s and accelerated into 2022–2025. Iran and Iranian-origin Shahed drones were launched in large numbers against regional targets and supplied to proxies or partners, a model later mirrored by Russian forces in Ukraine that used relatively inexpensive loitering munitions to force defenders into costly responses. CSIS+1

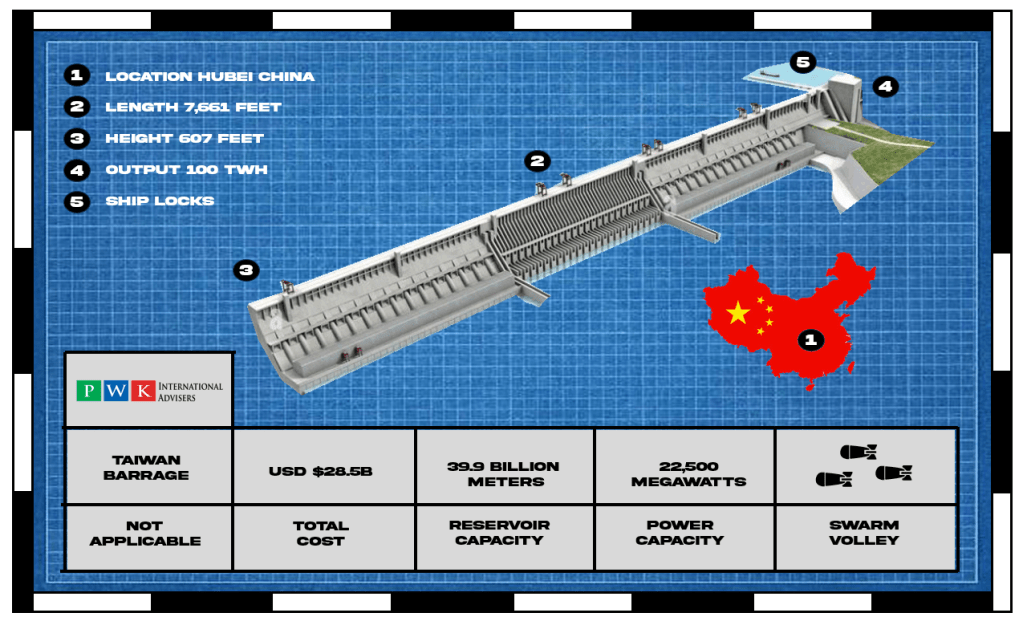

CAPTION: After all the expert wargaming and think tank analysis of a 2027 Taiwan scenario where China finally enforces it's irredentist claims and invades the much smaller Taiwan, one brutal constant emerges: if China pushes across the strait, Taiwan can pull a single geological trigger that drowns the invasion before it begins. A coordinated swarm of missiles and drones—cheap, numerous, and impossible to intercept in full saturation could strike the Three Gorges Dam and send a wall of water roaring through the Yangtze basin.

When one-third of China’s economy sits downstream of a single dam, the smaller actor suddenly becomes the one with leverage. It’s the kind of asymmetric threat that keeps strategists awake: a small democracy holding the ability to plunge a superpower’s industrial core underwater in a single stroke.

The message is simple and devastating, some targets are too big to protect, and too critical to lose. In the new economics of modern conflict, Taiwan’s deterrence works because it can shatter the symmetry China depends on with one well placed hit that punches far above it's weight class.

Great Powers and Non State Actors

State and non-state actors have optimized for this economic logic in different ways. Russia has invested in quantity and improvisation—mixing legacy cruise missiles and newer glide munitions with large numbers of relatively low-cost drones; Iran and its proxies have scaled production and export of loitering munitions and remote platforms; China has pursued sheer inventory depth and precision strike capacity as part of a campaign to overwhelm an opponent in the opening phase of a cross-Strait fight; and non-state actors have become experts at exploiting civilian infrastructure and information gaps to multiply effect while minimizing their own exposure. These optimizations are not accidental tactical adaptations; they are deliberate strategies to convert the defender’s technological edge into an economic and operational liability.

The era of unfair fights therefore forces a reframe. Victory is no longer only a function of better platforms or keener sensors; it is a function of how systems behave under massed, economically coercive attack and how quickly doctrine, procurement, and command structures can shift from a scarcity model to one that anticipates abundance. The rest of this report will trace the operational consequences of that reframe and then lay out practical pathways—across policy, force structure, and industrial choices—to blunt the asymmetric calculus that now defines the battlefield.

Over 86% of US Air Force Airmen and Space Force Guardians identify as GAMERS.

What at first glance looks like nostalgia is actually a sandbox for testing and refining skills like organization, resource management, health and rapid sense making in complex kill chains that require team work and restraint.

The most sought after first person view (FPV) drone pilots are gamers from Ukraine who have built a competitive scoring system for their time boxed and semi-autonomous kill web victories and body counts.

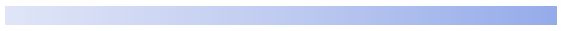

Wargaming and a culture of gaming skills are becoming central to the development and implementation of Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) systems, which are designed to create “unfair fights” by unifying sensors and shooters across all warfighting domains including air, land, sea, cyber, and space.

The core of this application lies in using realistic, competitive simulations—digital or tabletop—to test and refine rapid decision-making and multi-domain integration under immense time pressure and uncertainty.

Gaming culture, particularly the proficiency in complex digital environments, trains personnel to quickly process vast amounts of data, adapt to continuously changing scenarios, and utilize advanced tools like Artificial Intelligence (AI) to identify targets and recommend optimal kinetic or non-kinetic responses faster than an adversary can, effectively shortening the “sensor-to-shooter” kill chain and gaining a decisive asymmetric advantage.

From Missile Command to Golden Dome

When Dave Theurer launched Missile Command with Atari in 1980, I blew all my quarters trying to master the game. There were no hypersonic glide vehicles then, only ICBMs, SLBMs, and the occasional Tupolev Backfire bomber. Still, the math felt identical. Lives depend not on perfect execution but on how you manage scarcity under pressure.

Years later, after work on Patriot, THAAD, MEECN, SMART-T, and DD{X}, I kept asking the same question: are we still playing Missile Command at an ever grander scale, or do we need to change the rules entirely?

What would Sun Tzu do here I wondered?

The cruel truth of that arcade game is also the cruel truth of modern air and missile defense: the attacker enjoys effectively unbounded inventory; the defender faces finite interceptors, reload delays, logistic chains, and fragile sensors. You cannot intercept everything. You will take damage. The question, in many conceivable conflicts, is not whether cities fall but when. That arithmetic — attrition plus economics — is the engine that drives the contemporary shift from layered point defenses to proposals for continental-scale systems like Golden Dome.

Golden Dome: Washington’s Monument to the Unfair Fight

Golden Dome is best read as an attempt to build a new set of rules inside a world that has already changed. Announced publicly in 2025 as a multi-year, multi-hundred-billion-dollar effort to fuse space-based sensing, terrestrial sensors, directed energy, and autonomous engagement into a single defensive organism, Golden Dome reframes national missile defense as an integrated, AI-native kill-web rather than a collection of siloed batteries. The headline price—reported in the press as roughly $150–$175 billion in initial tranches—signals a political and strategic bet: scale the sensor and effect layers until the arithmetic that favors attackers is reversed or at least blunted. Politico+1

That bet is not merely monetary; it is doctrinal. Where traditional missile defense assumed slow, predictable engagements with clear friend-or-foe signatures and a human in the loop, Golden Dome assumes the opposite: near-continuous launches, hybrid ballistic–cruise–hypersonic salvos, AI-driven deception, electromagnetic and cyber disruption, and the persistent risk of sensor saturation. The system’s ambition is both defensive and structural: build an immune system for the homeland whose nerves are satellites and whose cognition is machine learning.

Enterprise Architecture and Government Reference Architecture

The conceptual architecture is elegant in its schematic and brutal in its requirements. At the top level:

• Space-layer detection: LEO/MEO constellations designed to detect launches and provide persistent wide-area tracking that cuts the observer-to-decision time from minutes to seconds. Golden Dome intends to exploit the advantages of space for global, redundant sensing. Politico

• Wide-area persistent sensors and edge fusion: ground and airborne sensors streaming continuous feeds into distributed edge compute nodes to support early characterization and classification.

• AI-driven classification & prediction: machine learning assigns threat type, intent probability, and likely impact point while predicting intercept solutions in compressed timeframes.

• Layered kinetic and non-kinetic effectors: a mix of directed energy arrays (lasers and high-power microwaves), uncrewed interceptor swarms, conventional interceptors for mid-course engagement, and point defenses for last-ditch shots.

• Boost-phase and glide-phase ambitions: early detection and engagement options intended to collapse the kill chain before lethal reentry or maneuvering glide vehicles create terminal ambiguity.

• Distributed command-and-control: an edge-centric C2 that pushes autonomy out to local nodes while retaining human supervisory control to manage escalation risks and political constraints. Lockheed Martin+1

The Three Pillars Revisited

Golden Dome’s engineering narrative can be summarized in three mutually reinforcing pillars — AI-driven C2, directed energy, and uncrewed interceptor layers — each of which addresses a specific dimension of the Missile Command problem.

1) AI-Driven Command and Control

Human operators are essential but insufficient when decision windows shrink below human reaction times. AI isn’t proposed as a replacement for people; it is proposed as the system that scales human intent across millions of sensor points, optimizes firing sequences, deconflicts simultaneous engagements, and manages attrition in near-real time. This is a doctrinal leap: supervisory control, not the old human-in-the-loop checkbox, becomes the default. The payoff is speed and volume; the risk is failure modes from adversarial inputs and deceptive ML attacks unless rigorously engineered and overseen.

2) Directed Energy Weapons

Lasers and high-power microwaves change the cost calculus: speed-of-light engagement and, effectively, an “infinite” magazine measured only in kilowatt-hours rather than millions per shot. Recent demonstrations and field tests by major primes show directed-energy prototypes reaching the 100–300 kW class, which under certain conditions can defeat small drones and degrade incoming projectiles. But lasers bring new tradeoffs: atmospheric attenuation, cloud cover, thermal management, and, critically, an industrial base for mobile, high-density power generation. Golden Dome bets that these engineering thresholds can be crossed at scale. SPIE+1

3) Uncrewed Interceptor Layers

If lasers are the continuous bullet, swarming uncrewed interceptors are the continuous launcher. Cheap, autonomous interceptors can be expended in mass against drone swarms or used to physically intercept cruise or hypersonic threats in the midcourse. Networks of inexpensive drones change the defender’s scarcity model — if you can generate launchers in quantity and coordinate them through AI, the attacker’s numerical advantage is eroded.

Industrial and Market Implications

Golden Dome will rearrange procurement, industry, and investment in predictable ways. New primes and deep-tech companies focused on autonomy, sensor fusion, constellation ops, and real-time ML (firms like Anduril, SpaceX, Palantir, and others named in reporting about program participation) stand to play vital roles in software-centric defense. Legacy primes will need to pivot from hardware-centric programs to platforms that integrate massive software, edge compute, and space services. For venture ecosystems, billions will gravitate to companies that solve power generation for directed energy, thermal management, resilient ML, and cheap uncrewed interceptors. The margin is in software-defined defense rather than single-purpose missiles. Engadget+1

Constraints, Weaknesses, and the Unfair-Fight Counter Punch

Golden Dome is powerful on paper; it is not invulnerable in practice. The biological organism metaphor helps locate its pathologies:

• Economics and sustainment: satellite constellations, power plants for directed energy, and millions of cheap interceptors create supply-chain, lifecycle, and fiscal slog-matches that can themselves be targeted by adversaries.

• Environmental and physical limits: high-power lasers are degraded by smoke, clouds, and precipitation; directed energy is not a universal cure. Solar storms, atmospheric effects, and geographic baselines limit blanket coverage.

• Cyber and deception: AI systems are vulnerable to data poisoning, spoofing, and adversarial examples; an attacker who successfully corrupts the sensory picture can generate misallocations of interceptors or induce destructive self-defeating behavior.

• Attribution and escalation: space-layer sensing and autonomous fires create ambiguous escalation paths. Who authorized a LEO-launched interceptor? Who pays the diplomatic price if a civilian satellite is damaged?

• Asymmetric countermeasures: cheap saturation, decoys, expendable balloons, electronic warfare, EMP, and the hollowing-out of space infrastructure (jamming or blinding satellites) remain practical and deniable counters that can restore the attacker’s arithmetic.

• Political and legal limits: the deployment of space-based weapons, offensive-capable directed energy, and automated kill chains raises arms-control and domestic oversight questions that will constrain operational use and force posture. The Guardian

Strategic Consequences

Golden Dome reframes deterrence: it seeks to make massed salvos less effective and more expensive for attackers, but it also institutionalizes new failure modes. A partially fielded Golden Dome could raise expectations in allied capitals for near-perfect protection, increasing brittleness in policy choices and the domestic political cost of early failures. It may also prompt adversaries to accelerate countermeasures and asymmetric doctrines — the classic offense-defense spiral writ in sensors and software.

Golden Dome is Washington’s attempt to change the rules so defenders can survive a fight of overwhelming numbers. The architecture is promising — now, the hard work begins: proving that the math can be reversed without introducing new pathologies that make the system worse than the problem it is meant to solve.

Top Six Takeaways

1. The Defender Must Punch Above Its Weight Class

Unfair fights reward attackers who can generate mass cheaply. Golden Dome’s central bet is that AI, directed energy, and autonomy allow defenders to punch harder, faster, and more cheaply than ever before—turning scarcity into abundance.

2. The Cost Curve Is the Real Battleground

Patriot missiles cost millions; many threats cost thousands. Directed energy and uncrewed interceptors are the first technologies capable of flipping that economic trap and restoring sustainable defense at scale.

3. Saturation Is the New Normal

Whether the threat is drones, cruise missiles, hypersonics, or multi-vector salvos, the defining feature of modern conflict is volume. Golden Dome is built not to avoid saturation, but to survive it.

4. AI Is Now the Decisive Weapon

No human can manage thousands of tracks, decoys, and deception operations at once. AI-driven C2 is not optional—it is the only way to compress decision cycles enough to matter.

5. Defense Must Become a Living System

Golden Dome reframes national defense as an organism: sensors as nerves, AI as cognition, interceptors as antibodies. Resilience comes not from a wall, but from distributed adaptation.

6. The Unfair Fights Are Already Here

Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, and non-state actors have optimized for asymmetric offense. Golden Dome is America’s first attempt to design a defense that expects the unexpected—a structure built not for the last war, but for the coming one.

Conclusion — The Unfair Fight Ahead

Unfair fights are no longer a hypothetical—they are the operating system of modern conflict.

The purpose of this report is not war game nostalgia. It is about clarity. Today’s “cheaper is better” war between the factories has taught one lesson above all others: once the defender is overwhelmed, no amount of bravery or precision can save them. You can shoot skillfully, you can time your intercepts perfectly, and still the final city will burn. Golden Dome is the most ambitious attempt in history to defy that fatal logic—to transform an unfair fight into a fair one, or perhaps to engineer an unfair one in America’s favor.

That ambition carries the tonnage of a national gamble. It combines AI, directed energy, autonomous interceptors, and space-based sensors into what is effectively a continental-scale defense organism—an immune system for national survival. The stakes demand that the public understand what is being built: the logic behind it, the risks embedded within it, the inevitability of mass attack, and the new logic of low cost, attritable asymmetric weapons.

Golden Dome attempts something extraordinary, something no wargame ever achieved: to survive the unwinnable game.

It may be the Manhattan Project of our lifetime: a national attempt to rewrite the math of asymmetry before asymmetry hardens into destiny. Whether America can architect that outcome is one of the defining questions of twenty-first–century security—and the answer may determine not only the future of missile warfare, but the long-term survivability of our advanced civilization itself.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

COLORS

OF MONEY

HOW THE

US FUNDS

INNOVATION

DETERRENCE &

POWER PROJECTION

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

LEADERSHIP

TECHNOLOGY

AND THE NUCLEAR

COMMAND CHAIN

ADAPTING FOR AN

UNCERTAIN FUTURE

Sources, Acknowledgements and Image Credits

{A} Unfair Fights | From Missile Command to Golden Dome is an Expert Network Report written by PWK International Managing Director David E. Tashji November 22, 2025. (C) 2025 PWK International. Attribution: (C) 2025 PWK International All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, or academic work, or as otherwise permitted by applicable copyright law.

“Unfair Fights” and all associated content, including but not limited to the report title, cover design, internal design, maps, engineering drawings, infographics and chapter structure are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use, adaptation, translation, or distribution of this work, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.

This report is a work of non-fiction based on publicly available information, expert interviews, and independent analysis. While every effort has been made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any employer, client, or affiliated organization.

All company names, product names, and trademarks mentioned in this report are the property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. No endorsement by, or affiliation with, any third party is implied.

{A.1} Unfair Fights | New Weapons in the Science War of the Century. Engineering drawings by PWK International. Russian Federation Belgorad and Poseidon; Ukraine FPV Fiber Optic Drone; Iran Shahed 238 micro-jet powered delta wing drone; Taiwan and China Three Gorges Dam; drawings by David E. Tashji (C) November 22, 2025 PWK International. All Rights Reserved.

{B} Cover Image: A B-52 Stratofortress leads a formation of Air Force and Navy F-16 Fighting Falcons, F-15 Eagles, and F-18 Hornets over the USS Kitty Hawk, USS Nimitz and USS John C. Stennis Strike Groups during Exercise Valiant Shield exercise Aug.14 in the Pacific. The forces participated in Valiant Shield, the largest joint exercise in the Pacific this year. Held in the Guam operating area, the exercise includes 30 ships, more than 280 aircraft and more than 20,000 servicemembers from the Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. (U.S. Navy photo/Petty Officer 2nd Class Jarod Hodge).

(C) Space services and drone warfare vignette drawing by (C) 2026 PWK International

(D) President Donald Trump speaks with Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, Space Force Vice Chief of Operations Michael Guetlein, and others after the announcement of the Golden Dome missile defense system at the White House in Washington, D.C., May 20, 2025. Photo by Joyce N. Boghosian/ZUMA Press Wire via Reuters Connect

(E) Additional Sources:

- “What is the Golden Dome missile defense shield?” — Reuters (May 2025)

Clear, balanced overview of the Golden Dome announcement, budget estimates, and initial program questions.

https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/what-is-golden-dome-missile-defense-shield-2025-05-21/ . Reuters - “Golden Dome: America (Lockheed Martin program page)”

Industry framing and capability claims for a Golden-Dome-style architecture. Useful for comparing vendor messaging to independent reporting.

https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/missile-defense/golden-dome-missile-defense.html . Lockheed Martin - “Delays, setbacks loom over Trump’s Golden Dome missile shield” — Reuters (Nov 2025)

Reporting on program delays, implementation challenges and political context (useful for program risk analysis).

https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/delays-setbacks-loom-over-trumps-golden-dome-missile-shield-2025-11-21/ . Reuters - Congressional Research Service (CRS) — Hypersonic Weapons: Background and Issues for Congress

Authoritative primer on hypersonic threats, technological challenges, and defense implications. Good for the hypersonics section.

https://sgp.fas.org/crs/weapons/R45811.pdf . FAS Project on Government Secrecy - CRS / Congressional product — PATRIOT Air and Missile Defense System for Ukraine (cost data)

Official congressional product citing Patriot system cost estimates (including interceptor unit-cost references). Useful for the cost-curve argument.

https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IF12297 . Congress.gov - “What is the Patriot missile system and how is it helping Ukraine?” — Reuters (Jul 2025)

Short explainer that reiterates interceptor cost estimates and operational constraints—handy for the “$4M per shot” point.

https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/what-is-patriot-missile-system-how-is-it-helping-ukraine-2025-07-14/ . Reuters - HESA Shahed-136 overview & cost reporting (open-source briefing / OSINT summaries)

Background on the Shahed family, reported unit-cost ranges, and their operational use in 2022–2024 conflicts (Ukraine, regional strikes). Useful for the low-cost-munitions case study.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HESA_Shahed_136 and complementary OSINT: https://osmp.ngo/collection/shahed-131-136-uavs-a-visual-guide/ . Wikipedia+1 - Institute for the Study of War (ISW) — Russian Offensive Campaign Assessments

Regular operational reporting on Russia’s use of glide bombs, cruise missiles, and massed drone strikes in Ukraine (excellent primary open-source analysis).

https://understandingwar.org/research/russia-ukraine/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-updates/ . Understanding War - “Drones in the Nagorno-Karabakh War: Analyzing the Data” / CSIS coverage & Army report

Empirical lessons from Azerbaijan’s 2020 use of TB2s and loitering munitions—perfect for the Nagorno-Karabakh vignette.

CSIS: https://www.csis.org/analysis/air-and-missile-war-nagorno-karabakh-lessons-future-strike-and-defense ; U.S. Army catalog: https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2023/01/31/693ac148/21-655-nagorno-karabakh-2020-conflict-catalog-aug-21-public.pdf . CSIS+1 - Houthi attacks on shipping — Reuters coverage / CFR backgrounder

Reporting and analysis of Houthi multi-vector strikes against commercial shipping and naval responses in the Red Sea (supports the “drain interceptors / impose cost” vignette).

Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/shipping-firms-avoid-red-sea-houthi-attacks-increase-2023-12-18/ ; CFR Global Conflict Tracker: https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/war-yemen . Reuters+1 - 9/11 Commission — Final Report (2004) (primary source)

The canonical account of 9/11, essential primary source for the “turn our own apparatus against us” case study. https://9-11commission.gov/report/ and full PDF: https://govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-911REPORT . 9/11 Commission+1 - Atlantic Council / other think-tank work on Chinese surveillance ecosystem

Strong, well-documented studies on the global spread of Chinese surveillance technologies and attendant influence/surveillance risks (supports the supply-chain surveillance vignette).

https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/issue-brief/chinese-surveillance-ecosystem-and-the-global-spread-of-its-tools/ . Atlantic Council - DHS / CISA and reporting on insecure Chinese-made cameras / critical infrastructure warnings

Practical government guidance and documented risk assessments on Chinese-origin IoT and camera products used in critical infrastructure. (Example reporting): https://industrialcyber.co/cisa/dhs-warns-chinese-made-internet-cameras-pose-espionage-threat-to-us-critical-infrastructure/ . Industrial Cyber - Directed energy technical & oversight background (CRS & industry pages / Breaking Defense / Raytheon / Lockheed) Directed-energy claims (kW classes, operational tradeoffs, program timelines). CRS directed energy primer: https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46925 ; Raytheon overview: https://www.rtx.com/raytheon/what-we-do/integrated-air-and-missile-defense/lasers ; Lockheed directed energy page: https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/directed-energy.html ; reporting on fielding/testing: https://www.defensenews.com/…/armys-high-energy-laser-competition-to-kick-off-early-next-year/ . Defense News+3Congress.gov+3RTX+3

- AI / Autonomy in C2 — RAND, CSIS, and service research

Authoritative analyses on how AI can be incorporated into command-and-control systems and the risks (data poisoning, adversarial inputs, supervisory control models). Useful for your AI-C2 pillar.

RAND working paper on AI in military affairs: https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WRA4004-1.html ; RAND on ML for C2: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA263-1.html ; CSIS AI & autonomy program page: https://www.csis.org/programs/wadhwani-ai-center/research-themes/ai-autonomy-and-national . RAND Corporation+2RAND Corporation+2 - Space sensors & missile-warning architectures (technical whitepapers / industry analysis)

Papers and technical overviews on how LEO/MEO constellations and distributed sensing could underpin a Golden-Dome style system. Useful when describing sensor/edge-fusion requirements.

Space sensors whitepaper: https://nipp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Space-Sensors-2023.pdf ; industry/analysis piece on LEO/MEO roles: https://flightplan.forecastinternational.com/2025/05/23/how-leo-meo-and-geo-satellites-could-power-trumps-golden-dome/ . NIPP+1 - Reporting on operational tests (e.g., LRDR) and relevant radar capability — Reuters coverage

Useful evidence for “ground-based radars that could link into Golden Dome” and realistic sensor performance.

https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/us-tests-radar-that-could-link-into-golden-dome-detect-china-russia-threats-2025-06-24/ . Reuters - Additional reporting & program critiques (Guardian / Washington Post)

Selected articles useful for political narrative, international reaction, and program-level critique. Example: Guardian summary of the announcement and timelines; Washington Post coverage of state reactions. Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/may/30/trump-golden-dome-missile-defense ; Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2025/05/27/north-korea-trump-golden-dome/ . The Guardian+1 - The Nagorno-Karabakh case (2020): Azerbaijan’s use of Turkish Armed MALE UAS (notably the TB2) and loitering munitions against Armenian air defenses and armor demonstrated how relatively low-cost remotely piloted systems can collapse traditional defenses and produce rapid operational outcomes. Military Strategy Magazine+1

- Hamas’ October 7, 2023 assault on Israel: a coordinated mix of rockets, infiltration, communications disruption, and surprise ground action produced asymmetric shock and localized operational success against an ostensibly superior adversary’s security apparatus. The attack highlighted how surprise, timing, and unconventional combinations of means can produce disproportionate effects. CSIS+1

- 9/11 as an archetype of turning a system inward: on 11 September 2001, 19 hijackers used commercial aviation—its fuel, aircraft, and routes provided by Western aviation infrastructure—to produce catastrophic effect at effectively zero cost to the attackers, illustrating how high-value civil systems can be exploited as weapons when defenders fail to anticipate asymmetric uses of familiar tools. GovInfo

- Supply-chain surveillance and influence: over the last decade, the global diffusion of Chinese-made sensors, cameras, and networked consumer devices has created a commercial surveillance footprint that state actors can exploit for intelligence, influence, and coercion at marginal cost—turning everyday devices into vectors of strategic effect in peacetime and crisis. Brookings PWK International New England PWK International New Mexico PWK International Silicon Valley

- All registered trade marks and trade names are the property of the respective owners. Missile Command is considered one of the all-time classic video games from the golden age of arcade games. It is also noted for its manifestation of the Cold War’s effects on popular culture in that it features an implementation of National Missile Defense and parallels real-life nuclear war. Designed by David Theurer for Atari in 1980, the arcade game is played by moving a crosshair across the sky background via a trackball (a first in it’s time) and pressing one of three buttons to launch a counter-missile from the appropriate battery. Counter-missiles explode upon reaching the crosshair, leaving a fireball that persists for several seconds and destroys any enemy missiles or aircraft that enter it. The three batteries provided are each armed with ten missiles; a battery becomes useless when all of its missiles have been launched or if it is destroyed by enemy fire. In the 1991 film Terminator 2: Judgment Day, John Connor plays the game in an arcade, echoing the film’s theme of a future global nuclear war. The game inevitably ends once all six cities are destroyed and the player neither has any in reserve nor earns one during the current level. Like most early arcade games, there is no way to “win”; the enemy weapons become faster and more prolific with each new level. The game, then, is just a contest in seeing how long the player can survive. On conclusion of the game, the screen displays “The End”, rather than “Game Over”, signifying that “in the end, all is lost. There is no winner”.

- Additional primary documents, downloadable / shareable

- 9/11 Commission — Final Report (PDF) — https://govinfo.gov/app/details/GPO-911REPORT . GovInfo

- CRS Hypersonic report (PDF) — https://sgp.fas.org/crs/weapons/R45811.pdf . FAS Project on Government Secrecy

About PWK International

PWK International is a strategic research and advisory firm focused on the intersection of advanced technology, geopolitics, and the business of government. We help executives, innovators, and policymakers navigate the emerging defense landscape—one shaped by autonomy, artificial intelligence, and the accelerating shift toward software-defined warfare. Our work blends deep technical insight with strategic storytelling, translating complex trends into clear narratives that deliver decision grade insights for data driven leaders.

Our team brings decades of experience across missile defense, intelligence systems, space architecture, and national-level command-and-control programs. From cutting-edge defense innovation to the granular mechanics of government acquisition, we draw from real-world assignments with agencies, national laboratories, and major contractors. This allows PWK International to provide clients with rare visibility into how strategy, policy, and emerging capabilities collide to shape the future of American power.

At the core of PWK International is a belief that technology is only meaningful when paired with clarity—and clarity only matters when it drives action. Whether we are producing executive reports, designing wargames, shaping corporate narratives, or advising on multi-billion-dollar programs, our mission is the same: help leaders see further, think sharper, and compete smarter. In an era defined by unfair fights and exponential change, PWK International equips organizations with the insight and confidence needed to win on tomorrow’s battlefield.