The United States government is far and away the biggest customer in the world. It spends hundreds of billions of dollars each year on defense, intelligence, technology, and professional services in a perpetual race with great power competitors and with a trillion dollar addiction to “the art of the possible” on land, at sea, in space and in cyberspace. Tax payer funds move through a complex and often opaque architecture of contract vehicles that quietly shape who can compete, how fast agencies can buy, and which companies ultimately win sustained access to government missions and ever accelerating technology refresh initiatives. For industry, understanding this architecture is no longer only for the finance team; it is a strategic requirement for growth, relevance, and survival in the fiercely competitive “smart technology in great power competition” market.

From government-wide vehicles like GSA Multiple Award Schedules and GWACs, to mission-specific frameworks such as OASIS, SeaPort, and agency-unique IDIQs across the Air Force, Space Force, Navy, and Intelligence Community, these contract vehicles act as pre-approved pathways for federal spending. They determine competitive dynamics, set the rules for teaming and task orders, and increasingly serve as the front door for innovation entering national security.

Yet for many companies—especially those new to government work—the landscape remains fragmented, confusing, and poorly explained. Not anymore.

This report is the start of your journey to an informed understanding of the major federal contract vehicles in use today. It explains how and why agencies rely on them, and outlines the strategic implications for companies seeking to do business with the U.S. government. Rather than serving as a compliance manual, this blueprint is intended as a strategic guide—helping leaders understand where opportunity concentrates, how procurement decisions are really made, and how to position capabilities within the government’s preferred buying channels.

| Vehicle Type | What It Is | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| GSA Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) | Long-term government-wide contract with pre-negotiated pricing. | Agency buys goods & services off the shelf. |

| Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity (IDIQ) | Base contract; agencies issue task orders later. | Flexible delivery — especially for services. |

| Government-Wide Acquisition Contracts (GWACs) | IDIQs open to all agencies managed by a lead agency. | Primarily IT and tech services. |

| Multiple Agency Contracts (MACs) | Like IDIQs but primary agency negotiates; others use. | Broad services/products across agencies. |

| Blanket Purchase Agreements (BPAs) | Pre-arranged recurring purchase orders. | Rapid buys for repetitive needs. |

| Other (BOAs, task orders) | Agreements that set terms for future orders. | Operational flexibility. |

The Hidden Architecture of Federal Buying

At scale, the federal government does not buy capabilities one contract at a time—it buys through pre-structured pathways designed to control risk, time, and competition. Contract vehicles exist because they allow agencies to separate access from execution: vendors are vetted once, pricing and terms are negotiated in advance, and mission owners can issue task orders rapidly when needs arise. This architecture prioritizes predictability and compliance over novelty, which explains why speed in government acquisition is often achieved not through innovation in contracting, but through disciplined reuse of existing vehicles.

These vehicles also reflect how the government manages uncertainty. Broad, government-wide vehicles reduce transaction costs and encourage competition, while service- or mission-specific vehicles preserve institutional control and continuity. In practice, this creates layered markets: an open front door for commoditized or advisory services, and tightly managed corridors for sensitive, operational, or sustainment work. Understanding which corridor a capability must travel through is as important as the capability itself, yet this distinction is rarely made explicit in acquisition guidance or public discourse.

Most importantly, contract vehicles quietly shape behavior across the industrial base. They influence how companies organize themselves, how they team, when they invest, and even which customer problems they choose to pursue. A firm aligned to the wrong vehicle may appear competitive on paper but remain structurally disadvantaged in execution. Conversely, companies that align early to the right vehicles often enjoy years of asymmetric access. In this sense, contract vehicles are not administrative tools—they are decision-forcing mechanisms that reveal how the government intends to buy, scale, and sustain capability over time.

Contract Vehicles as Signals of Institutional Intent

Every major contract vehicle reflects a set of institutional decisions about speed, control, and acceptable risk. When an agency relies on a government-wide acquisition contract, it is signaling a preference for standardization, broad competition, and administrative efficiency. When it creates or heavily favors a service-specific or mission-owned vehicle, it is signaling the opposite: tighter governance, deeper familiarity with vendors, and a willingness to trade openness for operational continuity. These signals matter because they indicate not just how the government plans to buy, but what kinds of behavior it intends to reward.

Over time, these signals harden into patterns. Vehicles designed for professional services and integration work tend to accumulate recurring task orders and long-term relationships, reinforcing incumbency and institutional memory. Vehicles positioned closer to research, experimentation, or rapid acquisition may appear more dynamic, but often lack clear transition paths into production or sustainment. The result is a bifurcated system in which innovation and execution are frequently separated by design, not accident—each governed by different vehicles, incentives, and success metrics.

For industry, misreading these signals is one of the most common and costly strategic errors. Companies often interpret vehicle eligibility as opportunity, without accounting for the underlying intent of the vehicle’s sponsor or user community. Winning a spot on a contract vehicle does not guarantee relevance; it merely grants permission to compete within a specific behavioral framework. The organizations that succeed over time are those that treat contract vehicles as indicators of institutional priorities and align their investment, teaming, and capture strategies accordingly.

Federal government contract vehicles are centralized purchasing agreements that allow agencies to acquire products and services more efficiently than through individual standalone contracts. As of early 2026, the landscape is shifting toward consolidated, "Best-in-Class" (BIC) vehicles under the GSA's One Gov Strategy, while the Department of Defense (DoD) is undergoing a rigorous "mission-alignment review" of high-value small business set-aside contracts.

The following table categorizes major contract vehicles available for businesses targeting the Air Force, Space Force, Navy, and Intelligence Community.

| Service Area | Vehicle Name | What It Is | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal / Government-wide | GSA Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) | A long-term, government-wide contract providing access to millions of commercial products and services at fair and reasonable prices. | General procurement of commercial IT and professional services; highly flexible for various agency needs. |

| Federal / Government-wide | OASIS+ (Phase II) | A next-generation, Best-in-Class multi-agency contract (MA-IDIQ) that consolidates legacy OASIS, BMO, and HCaTS. | Complex, non-IT integrated professional services including engineering, logistics, and management. |

| Federal / Government-wide | Alliant 3 | An unrestricted Best-in-Class Governmentwide Acquisition Contract (GWAC) for comprehensive IT solutions. | Global, large-scale IT service requirements, including hardware, software, and integrated services. |

| Federal / Government-wide | NASA SEWP VI | A multi-award GWAC focused on commercial IT products and product-based services. | Streamlined acquisition of IT hardware, specialized software, and related services. |

| Air Force & Space Force | NSSL (Phase 3) | National Security Space Launch program, specifically Lane 1 and Lane 2 contracts. | Providing launch services for sensitive national security satellites and access to difficult orbits. |

| Air Force & Space Force | Digital University (DU) SBIR Phase III | A specialized IDIQ supporting digital literacy and training requirements. | Accessing AI/ML training, DevSecOps learning paths, and digital training sandboxes across the DoD. |

| Air Force | RISE IDIQ | Range IDIQ Support Effort, hosted by the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center. | Supporting range threat systems and associated contracting for Air Force ranges through 2026. |

| Navy | SeaPort-NxG | The Navy’s primary vehicle for acquiring support services in 23 functional areas. | Used by almost all major Navy commands for engineering and program management services. |

| Navy | NAWC-AD MSA IDIQ | Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division Mission Systems Avionics contract. | Focused on mission systems avionics support and services for DoD agencies. |

| Intelligence & Defense-wide | SETI (Systems Engineering, Technology, and Innovation) | A technology-agnostic IDIQ designed to solve complex, unique capability gaps. | Systems engineering and innovative IT solutions for the Intelligence Community and Combatant Commands. |

| Intelligence & Defense-wide | DTIC IAC MAC | Defense Technical Information Center Information Analysis Center Multiple Award Contract. | Providing RDT&E (Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation) services and R&D-related analytical support. |

| Intelligence & Defense-wide | SHIELD | Scalable Homeland Innovative Enterprise Layered Defense contract vehicle. | Supporting research, development, and prototyping for homeland missile defense initiatives. |

Not all contract vehicles are designed to do the same work, even when they appear similar on paper. Some are built to maximize market access and competition, others to integrate complex capabilities over time, and still others to preserve mission control within specific services or communities. Treating all vehicles as interchangeable procurement tools obscures their real function: each is optimized for a particular phase of government activity and a particular tolerance for risk, speed, and vendor dependence.

At the broadest level are market access vehicles, such as GSA Multiple Award Schedules and major GWACs. These vehicles are designed to expose agencies to a wide range of vendors and commercial solutions, reduce acquisition friction, and accelerate buying for repeatable needs. They favor compliance, scale, and pricing discipline, and they often serve as the first point of entry for companies seeking to establish a federal footprint. Their strength is reach; their weakness is differentiation. Success on these vehicles requires operational maturity more than technical novelty.

In contrast, capability integration and mission-controlled vehicles—including service-specific IDIQs and platforms like OASIS or SeaPort—prioritize continuity, institutional knowledge, and trusted execution. These vehicles concentrate spend among fewer vendors, emphasize teaming and past performance, and often dominate the flow of Operations and Maintenance dollars. While they can be harder to penetrate, they offer durability and depth for companies that align with the sponsoring organization’s long-term mission. Understanding which category a vehicle belongs to is essential, because it determines not just how companies compete, but how capabilities are absorbed, scaled, and sustained inside the government.

From Structure to Spend: How Vehicles Channel Funding

Once established, contract vehicles become the primary mechanism through which federal dollars are obligated, shaping not just who gets paid, but what kinds of work are funded over time. Research and development activities, early prototyping, systems integration, and long-term sustainment rarely flow through the same vehicles, even when they support the same mission. Instead, vehicles act as filters, directing different colors and categories of funding into distinct execution paths with their own rules, timelines, and competitive dynamics.

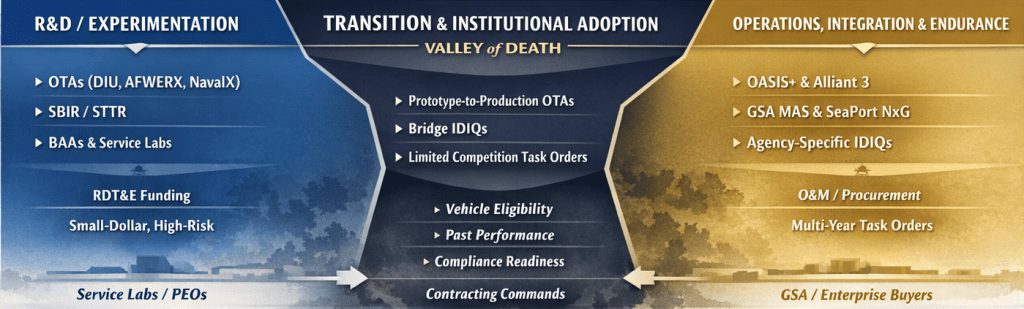

This separation has real consequences for how capabilities mature. Vehicles associated with R&D and experimentation tend to reward novelty, speed, and technical promise, but often lack the structural authority or budget continuity required to support scaling. Conversely, vehicles aligned with Operations and Maintenance spending prioritize reliability, workforce stability, and predictable delivery, often at the expense of rapid change. The transition between these domains is where many promising technologies stall—not because funding disappears, but because the next phase of spend is controlled by a different vehicle, administered by a different organization, and competed under entirely different assumptions.

Understanding this channeling effect is essential for strategic planning. Companies that focus exclusively on early-stage vehicles may achieve visibility without durability, while those that anchor themselves solely in sustainment vehicles risk irrelevance as missions evolve. Effective execution requires intentional sequencing: aligning capabilities, partnerships, and investments with the vehicles that govern each phase of the lifecycle. In this context, mapping vehicles to administering services and spend categories is not an academic exercise—it is a prerequisite for fiscally disciplined growth in the federal market.

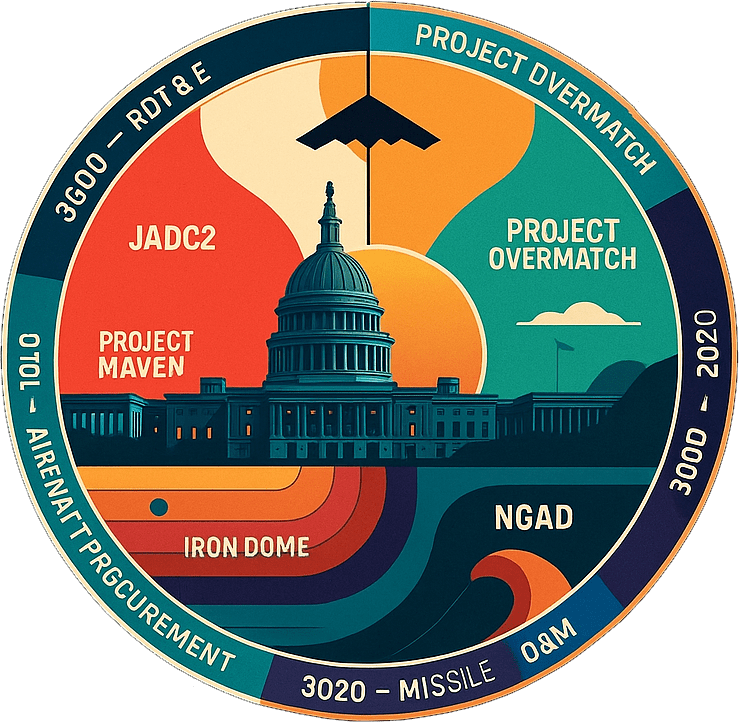

Major Defense Modernization Programs and Associated Contract Vehicles

Major defense modernization programs are typically executed through direct contracts or program-specific IDIQs (Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity) awarded to prime contractors, rather than the government-wide acquisition vehicles (GWACs) like GSA Schedules used for more general procurement. The following table illustrates how these high-dollar, high-profile programs map to specific contract mechanisms.

| Service Area | Program/Platform Name | Associated Contract Vehicle(s) | Prime Contractors & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joint / Multi-Service | F-35 Joint Strike Fighter | Program-Specific Production Contracts (e.g., N0001925C0070) | Lockheed Martin (prime), BAE Systems, Northrop Grumman, RTX (Pratt & Whitney engines). Contracts are issued by the Joint Program Office. |

| Navy | Columbia-Class SSBN Submarine | Program-Specific IDIQ (N00024-17-C-2117) & Block Buy Contracts | General Dynamics Electric Boat (prime), Huntington Ingalls Industries. Uses specific contract modifications and advance procurement funding mechanisms. |

| Navy | Ford-Class Aircraft Carrier | Program-Specific Block Buy Contracts (e.g., for CVN 80/81) | Huntington Ingalls Industries (Newport News Shipbuilding) (prime), General Atomics (EMALS/AAG systems). Uses specialized fixed-price-incentive contracts. |

| Air Force | NGAD (Next-Generation Air Dominance) Fighter (F-47) | Program-Specific Development/Production Contracts | Boeing reportedly won the initial contract for the first lot of jets; funding allocated for R&D. |

| Air Force & Navy | Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA) | IDIQ/Prototype Contracts (e.g., concept development contracts) | Anduril, Boeing, General Atomics, Northrop Grumman are involved in concept development. |

| Joint / DoD | Hypersonics Arena (R&D/Procurement) | Multiple R&D Contracts (Service-specific and DARPA-led) | Various contractors (e.g., Lockheed, RTX, Northrop Grumman) work under numerous R&D and eventual production contracts across services. |

| Air Force / DoD | Joint All Domain Command and Control (JADC2) | Various IDIQs, DIU Contracts, GWACs (e.g., ABMS contracts, Project Convergence contracts) | Leidos has a large intelligence contract; multiple vendors contribute across service initiatives (Air Force ABMS, Navy Project Overmatch). |

| Navy | Project Overmatch | Various NAVWAR/PEO C4I Contracts & IDIQs | Focuses on naval power for the joint force commander, with numerous IT and C4I-related contracts from Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVWAR). |

| Space Force | GPS Modernization | Program-Specific Space Systems Command Contracts (e.g., GPS III Follow On) | Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and others involved in developing and procuring new satellite constellations and ground systems. |

| Intelligence Agencies | Classified Programs / Advanced Tech | Specialized IDIQs (e.g., SETI, DIU prototyping) | Leidos, Northrop Grumman, and other cleared defense contractors. These use specific, often highly classified, contracting mechanisms for R&D and operations support. |

Key Takeaways From The Chart

Modernization & R&D: Programs like JADC2, Hypersonics, and AI/ML initiatives are more likely to use a wider variety of contract vehicles, including rapid prototyping authorities, IDIQs, and contracts through innovative units like the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU).

Major platforms including ships, aircraft, and submarines are almost exclusively procured via large, direct, program-specific contracts or block buys with single prime contractors.

At first glance, a directory of contract vehicles may appear purely administrative—a reference list of names, sponsors, and eligibility criteria. In reality, such a map reveals the power structure of federal acquisition. Every vehicle is administered by an organization that controls access, shapes competition, and influences how requirements are written and evaluated. Understanding who administers a vehicle is often more important than understanding the vehicle itself, because it points directly to where authority, budget influence, and institutional priorities reside.

When vehicles are mapped to their administering services and agencies, clear patterns emerge. The Air Force and Space Force emphasize speed, modularity, and portfolio management across their acquisition pathways, while the Navy’s vehicles tend to prioritize engineering depth, platform sustainment, and long-term workforce continuity. Intelligence Community vehicles are typically narrower, more opaque, and tightly governed, reflecting their operational sensitivity and reliance on trusted execution. These differences are not accidental; they are expressions of how each organization balances innovation, risk, and control.

Layering spend categories onto this map—research and development, prototyping and transition, and operations and maintenance—adds a final and critical dimension. Certain vehicles consistently dominate early-stage exploration, others control the flow of enduring O&M dollars, and only a small subset reliably bridge the two. By organizing vehicles along these lines, the directory becomes a strategic tool: it shows not just where contracts exist, but where influence accumulates, where budgets stabilize, and where long-term advantage is built or denied.

How Vehicles Shape Competition and Market Outcomes

Once contract vehicles are in place, they do more than organize buying—they actively shape the competitive landscape. Vehicles determine who is visible to the government, who is eligible to respond at speed, and who is structurally advantaged when requirements emerge. Over time, this creates stratified markets in which access is unevenly distributed and competition occurs within narrow, pre-defined boundaries. Winning a task order is often less about outperforming peers and more about already being positioned inside the right competitive arena.

These dynamics reinforce incumbency in subtle but powerful ways. Vehicles aligned to sustainment and operations tend to reward continuity, workforce presence, and institutional familiarity, making displacement difficult even when performance is uneven. Teaming arrangements, while framed as inclusive, often replicate existing hierarchies, with prime contractors controlling customer access and smaller firms competing for marginal roles. The result is a system where competition exists, but innovation is filtered, paced, and absorbed on institutional terms rather than market ones.

For industry, this means that competitive advantage is increasingly built upstream of any specific opportunity. Decisions about which vehicles to pursue, which partners to align with, and which agencies to prioritize shape outcomes years before a solicitation is released. Companies that treat vehicles as tactical pursuits often find themselves locked into low-margin, low-influence positions. Those that approach vehicles as instruments of market positioning are better able to concentrate effort, protect optionality, and build durable presence where government demand is most stable.

Strategic Positioning in a Vehicle-Driven Market

In a vehicle-driven market, success is rarely the result of opportunistic bidding. It is the outcome of deliberate positioning choices made years in advance, often before a specific requirement is visible. Companies that perform well over time treat contract vehicles as long-term infrastructure investments, not short-term revenue opportunities. They pursue access selectively, align internal capabilities to the vehicles that matter most, and resist the temptation to chase every open door simply because eligibility exists.

Different types of firms must position themselves differently. Venture-backed and non-traditional companies benefit from vehicles that emphasize experimentation, digital services, and rapid tasking, but they must be clear-eyed about where those paths end. Mid-tier firms face the challenge of balancing growth with focus, using vehicles to deepen relevance with specific customers rather than spreading effort thin across the enterprise. Large integrators, by contrast, use vehicles defensively as much as offensively—protecting incumbency, shaping teaming ecosystems, and anchoring long-term operations and maintenance revenue.

Across all categories, the most common failure mode is misalignment between vehicle strategy and business reality. Pursuing vehicles that do not match delivery capacity, cost structure, or customer access often results in sunk bid costs and stalled momentum. Disciplined organizations sequence their vehicle pursuits, partner intentionally, and periodically exit vehicles that no longer serve strategic objectives. In a system where access precedes opportunity, clarity of intent is the most underappreciated competitive advantage.

Guide to Federal & Intelligence Contract Vehicles in 2026

| Service / Agency | Vehicle Name | Exact Description | Primary Use & Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Wide | GSA MAS | The Multiple Award Schedule (Schedules) | Procurement of commercial products, IT services, and professional consulting. |

| Federal Wide | OASIS+ | Next-gen Multi-Agency IDIQ | Complex, non-IT professional services including Engineering and Logistics. |

| Federal Wide | Alliant 3 | Best-in-Class IT GWAC | Large-scale, global IT infrastructure and integrated digital solutions. |

| NASA / IT | SEWP VI | Solutions for Enterprise-Wide Procurement | Primarily IT products, cloud computing, and product-based services. |

| Navy | SeaPort-NxG | Navy’s primary service vehicle | Engineering, financial management, and program management support. |

| Air Force | SBEAS | Small Business Enterprise Application Solutions | Software development, cybersecurity, and data management for the Air Force. |

| Air Force | CONG IT | Consolidated IT Services | Management and maintenance of Air Force enterprise-level IT networks. |

| Space Force | Space Systems Command | National Security Space Launch (NSSL) | Space-based capabilities, launch services, and orbital logistics. |

| Intel / DISA | SETI | Systems Engineering, Technology & Innovation | Complex technical gaps requiring “non-traditional” engineering solutions. |

| Intel / DISA | Encore III | Multi-award IT Services IDIQ | 19 performance areas covering the full spectrum of IT life-cycle support. |

| Intel / NGA | CLOVER | NGA’s multi-award IDIQ | Specialized services for Geospatial Intelligence (GEOINT) and imagery. |

| Defense / Intel | DTIC IAC MAC | Information Analysis Center Multi-Award Contract | High-end R&D, data analysis, and technical evaluations for DoD/Intel. |

| Intelligence | SITE III | Solutions for the IT Enterprise | Managed services and infrastructure support for the DIA and IC partners. |

| DoD / Innovation | DIU Prototypes | Defense Innovation Unit OTAs | Fast-track “Other Transaction Authority” for commercial tech prototypes. |

| Health / HHS | CIO-SP3 / SP4 | IT Solutions and Partners | Comprehensive IT services with a focus on biomedical and health missions. |

What the Contract Vehicle Landscape Signals About the Future

The current proliferation of contract vehicles is not a sign of chaos—it is a signal of institutional adaptation. As missions grow more technical, timelines compress, and fiscal scrutiny increases, agencies are using vehicles to impose order on uncertainty. The trend is toward fewer, larger, and more durable vehicles with broader scope, longer periods of performance, and greater internal flexibility. This consolidation is often described as simplification, but in practice it reflects a desire for stronger central control over how capability is introduced, integrated, and sustained.

At the same time, vehicles are increasingly being used as instruments of policy, not just procurement. Set-aside structures, on-ramps, and pool designs are shaping the industrial base the government wants to see—not merely responding to what exists today. Vehicles are being designed to encourage certain behaviors: teaming over fragmentation, services over bespoke development, and incremental improvement over disruptive change. Innovation is still welcomed, but only insofar as it can be absorbed without destabilizing execution or sustainment.

For industry, this means the future will reward coherence over novelty. Companies that understand how vehicles reflect institutional priorities will be better positioned to anticipate shifts in demand and funding. Those that mistake access for endorsement, or experimentation for transition, will continue to struggle at scale. As contract vehicles become the dominant operating system of federal acquisition, strategic literacy in how they are designed, administered, and evolved will matter as much as technical excellence or price competitiveness.

Key Market Trends for 2026

Consolidation: Under the One Gov Strategy, there is a strong push to move more spend to GSA-managed vehicles like Alliant 3 and OASIS+ to improve commercial efficiency.

Small Business Scrutiny: The Department of Defense (DoD) is currently conducting a "line-by-line review" of all small business and 8(a) sole-source contracts valued over $20 million to ensure mission alignment and prevent impermissible pass-throughs.

OASIS+ Expansion: Phase II of OASIS+ launched in early 2026 with a continuously open submission model, adding five new service domains to its scope.

Cybersecurity Compliance: Full compliance with CMMC 2.0 is increasingly critical, with a phased rollout for DoD contracts involving sensitive information starting in late 2025.

Conclusion: Contract Literacy as Strategic Discipline

Just as Colors of Money demonstrated that budgeting is less about accounting and more about disciplined decision-making, this report shows that contract vehicles are not procurement mechanics—they are strategic infrastructure. They encode institutional intent, determine how risk is managed, and shape how capabilities move from concept to sustainment. Organizations that fail to understand this architecture often misdiagnose their challenges as technical or competitive, when in reality they are structural.

Effective engagement with the federal market requires more than getting on the right vehicle. It demands an understanding of why that vehicle exists, who controls it, and what kind of behavior it is designed to reward. Vehicles influence how companies invest, how they team, and how they sequence growth. When misaligned, they create friction, stalled transitions, and wasted capital. When aligned, they provide durable access, predictable execution, and a foundation for long-term relevance.

Ultimately, contract literacy is a form of strategic discipline. It enables leaders to move beyond reactive bidding and toward intentional positioning—aligning capabilities, customers, and funding pathways over time. As federal acquisition continues to consolidate around fewer, more powerful vehicles, the companies that succeed will be those that treat vehicles not as paperwork to manage, but as signals to interpret and infrastructure to plan against.

Top Six Takeaways

1.Disciplined, sequenced vehicle positioning is a prerequisite for sustainable growth in the federal market.

2.Contract vehicles are strategy encoded in process, not administrative conveniences.

3.Access precedes opportunity - being on the right vehicle matters more than any single bid.

4.Different vehicles dominate different lifecycle phases, from R&D to O&M; transitions are not automatic.

5.Administering organizations matter as much as vehicle terms, because they control priorities and behavior.

6.Misaligned vehicle strategies create structural disadvantage, regardless of technical merit.

Sources and Image Credits

{1} Valley of Death is an expert network report researched and written by PWK International Managing Director David E. Tashji. (C) 2025 PWK International. All Rights Reserved. Required Attribution: (C) PWK International 2026

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, reviews, or academic work, or as otherwise permitted by applicable copyright law.

“Valley of Death” and all associated content, including but not limited to the report title, cover design, internal design, maps, engineering drawings, infographics and chapter structure are the intellectual property of the author. Unauthorized use, adaptation, translation, or distribution of this work, in whole or in part, is strictly prohibited.

This report is a work of non-fiction based on publicly available information, expert interviews, and independent analysis. While every effort has been made to provide accurate and up-to-date information, the author makes no warranties, express or implied, regarding completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of any employer, client, or affiliated organization.

All company names, product names, and trademarks mentioned in this report are the property of their respective owners and are used for identification purposes only. No endorsement by, or affiliation with, any third party is implied.

{2} Our un-biased report includes mention of numerous investment firms, technology disruptors and their battlefield advantage innovations. All registered trade marks and trade names are the property of the respective owners.

Official Government Contract Vehicle Resources

- GSA Government-Wide Acquisition Contracts (GWACs) – Official GSA page explaining GWAC structure, ordering process, and major vehicles (e.g., 8(a) STARS III, Alliant 2, VETS 2). GSA GWACs – Government‑Wide Acquisition Contracts (GSA.gov)

- SeaPort Next Generation (SeaPort NxG) – U.S. Navy page describing SeaPort NxG as the primary multiple-award contract for professional support services. SeaPort NxG – NAVSEA (Navy.mil)

- Alliant 2 Governmentwide Acquisition Contract – GSA page on the Alliant 2 GWAC, a high-ceiling vehicle for broad IT solutions. Alliant 2 GWAC Overview (GSA.gov)

- VETS 2 Governmentwide Acquisition Contract – Official GSA info on the VETS 2 vehicle, set aside for SDVOSB firms. VETS 2 GWAC (GSA.gov)

Contract Vehicle Explanations & Industry Guides

- FedProposal: IDIQs, GWACs, and BPAs Explained – High-level explanatory article on how these vehicles function and how to identify them in procurement. IDIQs, GWACs, and BPAs Explained (FedProposal.com)

- Public Spend Forum Guide to GWACs and Multi-Agency Vehicles – Classic PDF primer explaining GSA schedules and GWACs (introductory industry context). GWAC & Multi‑Agency Vehicles Guide (PublicSpendForum.net)

Company Contract Vehicle Listings (Context for Market Examples)

- GovCIO Contract Vehicles – Example of corporate positioning across GSA, GWAC, and agency-specific vehicles. GovCIO Contract Vehicles (govcio.com)

- Sky Solutions Contract Vehicles – Lists common vehicles like 8(a) STARS III, OASIS+, eFAST, and SeaPort-NxG. Sky Solutions Contract Vehicles (skysolutions.com)

- 22nd Century Technologies Contract Vehicles – Another example of GWAC, IDIQ, GSA MAS, and DLA JETS 2 vehicles in practice. 22nd Century Technologies Contract Vehicles (tscti.com)

- Bowhead Contract Vehicles Resource – Example of how OASIS, MAS, STARS III, and SeaPort-NxG are used by industry. Bowhead Contract Vehicles Resource (bowhead.com)

- Technica SEWP V & SeaPort-NxG Info – Company page showing the NASA SEWP V GWAC and SeaPort vehicles in context. Technica Contract Vehicles (TechnicaCorp.com)

Supplemental Definitions & Broader Context

Government-Wide Acquisition Contracts — Wikipedia – Independent overview of GWACs, how they operate, and typical use cases. GWAC Overview (Wikipedia)

Glossary of Key Terms

1. Contract Vehicle

A pre-established contracting framework that governs how agencies buy goods and services, separating access to competition from task-level execution.

2. IDIQ (Indefinite Delivery, Indefinite Quantity)

A contract type that allows agencies to issue task orders over time within a defined scope, ceiling, and period of performance.

3. GWAC (Government-Wide Acquisition Contract)

An IDIQ contract administered by a lead agency and available for use by all federal agencies, commonly used for IT and professional services.

4. GSA Multiple Award Schedule (MAS)

A long-term, government-wide contract with pre-negotiated pricing and terms for commercial products and services.

5. Task Order

A specific request for work issued under a contract vehicle, defining scope, schedule, and funding for execution.

6. OASIS / OASIS+

GSA-administered multiple-award IDIQ vehicles focused on complex professional services and mission support.

7. SeaPort NxG (Next Generation)

The Navy’s primary contract vehicle for engineering and professional support services across multiple commands.

8. Administering Agency

The organization responsible for managing a contract vehicle, including governance, compliance, and access control.

9. R&D (Research and Development)

Early-stage funding and activity focused on exploration, experimentation, and technical risk reduction.

10. Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

Funding used to support ongoing operations, sustainment, workforce, and system upkeep—often the most durable source of spend.

11. Valley of Death

The gap between early innovation and scaled adoption, where promising capabilities fail to transition due to structural, funding, or contractual misalignment.

12. On-Ramp / Off-Ramp

Mechanisms that allow new vendors to enter, or existing vendors to exit, a contract vehicle during its period of performance.

13. Incumbency

The advantage held by existing contract holders due to familiarity, workforce presence, and past performance.

14. Teaming Arrangement

A formal or informal partnership between companies to pursue and execute work under a contract vehicle.

15. Lifecycle Alignment

The intentional sequencing of capabilities, funding, and contract vehicles across R&D, transition, and sustainment phases.

About PWK International

PWK International is a strategic advisory and research firm focused on the intersection of national security, technology, and government decision-making. The firm works with industry leaders, investors, and government organizations to help them navigate complex acquisition environments, align innovation with mission demand, and execute with fiscal and operational discipline. PWK’s work is grounded in direct experience across defense, intelligence, and civilian agencies, translating institutional realities into actionable insight.

PWK is known for producing clear, strategic analysis that moves beyond surface-level explanations. Its widely read report, Colors of Money, reframed federal budgeting as a question of strategy and execution rather than financial literacy, highlighting how funding categories, timelines, and authorities shape outcomes across the defense ecosystem. That work has informed how companies and decision-makers think about planning, risk, and long-term positioning in the federal market.

This report continues that tradition by examining contract vehicles as strategic infrastructure—revealing how procurement pathways shape competition, innovation, and sustainment across the Air Force, Space Force, Navy, and Intelligence Community. Together, PWK’s research and advisory work aim to equip leaders with the clarity needed to operate effectively inside the valley of death and within the new business of government.